Central Asia Journal No. 66

Sustainable Development of Agriculture in South and Central Asian Regions –

A Key to Prosperity

Dr. Mohammad Aslam Khan*

Dr. S. Akhtar Ali Shah**

Abstract

The growth in GDP of South and Central Asia cab be attributed to three major sectors of economy; industry, agriculture and services. However, major focus of governments’ attention in both regions in recent past has been industrial and service sectors. While the agriculture sector contributes one fifth to one fourth of GDP, in countries of the regions, its overall impact on national economies is far greater. For example it still employs one fourth to half the population of the countries in the regions. It also generates considerable income and employment opportunities in the non- farming communities within rural areas as well as in urban industries such as food processing, textile etc. In addition, it contributes to earn valuable foreign exchange through exports. Further, in recent years agricultural sector has assumed increased and renewed importance in the context of food security and environment. Few people could have accepted that countries in the regions will be able to feed their massively growing population. However, this impressive agricultural development in the regions also had environmental footprints, particularly in the course of green revolution in the form of land degradation (including water logging and salinity), desertification, and addition of agro-chemicals into food chains. The solution is not to slow development in agriculture but to seek a more sustainable agricultural production system. Unfortunately despite the impressive economic contribution of agricultural sector, more and more attention is being given to industrial and service sectors as these are considered to be the harbinger of development. The focus of this paper is to underscore the importance of sustainable development in agriculture, which is still the backbone of the regions’ economy and the performance of which, is tied up to the prosperity and economic growth and reduction of poverty in general and well being of rural population in the regions, in particular. In this context, the paper highlights major challenges that have emerged and need to be addressed by the planners and policy makers.

Key Words: Sustainable Development, Agriculture, Economy, Land use

Introduction

South and Central Asia is still predominantly rural. Presently almost 70 per cent of South and Central Asians live in rural areas as compared to only 35 per cent in Western Asia, 56 per cent in South East Asia and 60 per cent in the whole of Asia . Despite slow growth, with the exception of Iran and Kazakhstan, rural population still predominate in the countries of South and Central Asia (Table 1) and the agricultural sector is the kernel of rural economy. Its performance is closely tied up with both the growth of GDP and well being of masses. This paper analyzes the nature of agricultural resources in countries of the regions and the role they play in sustainable development of national

Table 1. Distribution of Rural Population in South and Central Asia.

Country |

Total population 2005 (000s) |

Rural population 2005 (000s) |

Rural Population Growth Rate (%) |

|

Number (000s) |

Percent share |

|||

Afghanistan |

25067 |

19327 |

77.1 |

3.35 |

Bangladesh |

153281 |

113930 |

74.3 |

1.34 |

Bhutan |

637 |

440 |

69 |

1.07 |

India |

1134403 |

808840 |

71.3 |

1.33 |

Iran |

69361 |

22954 |

33.1 |

-0.62 |

Kazakhstan |

15210 |

6525 |

42.9 |

-0.04 |

Kyrgyzstan |

5204 |

3341 |

64.2 |

0.83 |

Maldives |

295 |

195 |

66.1 |

-0.23 |

Nepal |

27093 |

22824 |

84.2 |

1.53 |

Pakistan |

158080 |

102945 |

65.1 |

1.3 |

Sri Lanka |

19121 |

16226 |

84.9 |

0.56 |

Tajikistan |

6550 |

4821 |

73.6 |

1.21 |

Turkmenistan |

4834 |

2547 |

52.7 |

0.87 |

Uzbekistan |

26593 |

16838 |

63.3 |

1.64 |

economies and highlights the major challenges that have emerged and need to be addressed on urgent basis. The paper starts by examining the role of agricultural sector in national economies, and as a source of livelihood. It highlights country wise GDP share of agriculture, volume of agricultural labor force and share of agricultural products in international trade. This section is followed by examining land use patterns and assessing the availability of cultivated land and other land uses. The growth and availability of agricultural land vis-à-vis agricultural population is covered in the third section to examine the pressure on land resources. The structural changes that have occurred in agriculture sector particularly in the form of heavy inputs of chemicals and their environmental implications have been assessed next followed by a discussion on emerging challenges.

Agriculture and Economy

South and Central Asia has experienced a major economic and technological transformation in the last few decades. This technological transformation has somewhat reduced agricultural share in national economies. Although it varies from country to country ranging from over one third in Afghanistan, Bhutan, Kyrgyzstan and Nepal to between one fifth and one third in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Iran and Kazakhstan are the mineral rich countries, where agricultural accounts for around ten per cent share of GDP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Agriculture and Economy in South and Central Asia

Agriculture is much more important in South and Central Asia as a source of livelihood. It employs more than ninety per cent of work force in Bhutan and Nepal, and about half the work force or over in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In all other countries, with the exception of Kazakhstan, it accounts for about a quarter of the work force.

Agricultural also has a major share in export from South and Central Asian countries. For example India alone exported agricultural commodities worth almost six billion dollars in 2005. Likewise Iran, Pakistan and Sri Lanka each earned more than one billion dollars from export of agricultural commodities (Fig.2).

Fig. 2. South and Central Asia: International Trade in Agricultural Products

Agriculture has also been precursor of industrial development in a number of countries of the regions and even today provides raw materials to several industries such as textile, food processing, pharmaceutical etc. Although data is not available to show the importance of agriculture in alleviation of rural poverty in South and Central Asia, the recently published World Development report quotes, “The recent decline in the $1-a-day poverty rate in developing countries—from 28 percent in 1993 to 22 percent in 2002—has been mainly the result of falling rural poverty (from 37 percent to 29 percent) while the urban poverty rate remained nearly constant (at 13 percent). More than 80 percent of the decline in rural poverty is attributable to better conditions in rural areas rather than to out-migration of the poor. So, contrary to common perceptions, migration to cities has not been the main instrument for rural (and world) poverty reduction.

Land Use Pattern

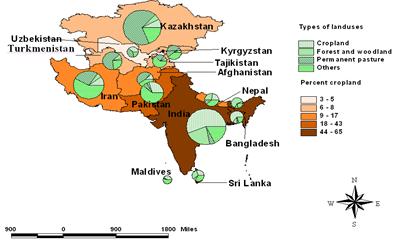

The land use pattern in the South and Central Asian regions has undergone continuous changes, manifesting the impacts of the dynamic and complex interplay of socio-economic, political and technological forces. A comparison of land use patterns in South and Central Asia, with the world shows a slightly higher share of croplands in the regions (Fig. 3). This is indicative of the pressure to expand agriculture to feed the burgeoning population particularly in South Asia.

Fig. 3. Percentage Share of Land Use in the World, Asia-Pacific and South and Central Asia

In response to the soaring population pressure, cropland continued to expand at the cost of forests and rangelands. Historical land use data shows that three distinct phases can be identified in terms of cropland expansion in the regions. During the first phase from 1850 to around 1950, cropland expansion was moderate. It was followed by a phase of rapid expansion from the middle of the twentieth century to 1980. Over 4 million hectares were added every year during this phase. During the third or current phase the cropland expansion has reduced and its share in agricultural growth has been overshadowed by contribution from increased intensification. In absolute terms though, the area under crop is still increasing in South Asia, where about 2.9 million ha was added between 1992 and 2002; maximum increase was in Nepal, followed by Pakistan, India and Bangladesh (Table 2). In Central Asia there was a net decrease in agricultural land with the maximum decrease in Kazakhstan, followed by small decreases in Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan . Tajikistan and Turkmenistan recorded net increase in agricultural land. The space for further development of agricultural land appears to be limited, and any further expansion in future, therefore, must take place in marginal areas, aggravating the problem of land degradation, which has already set its feet in the regions.

Permanent pasture is another land use related to agriculture. Geomorphology, climatic conditions and relatively limited agriculture in parts of the regions are some contributing factors to the greater share of permanent pastures particularly in Central Asia where this land use category accounts for over 50 percent share of land use. Afghanistan with 47 percent and Iran with 26 per cent are two other countries with vast area under permanent pasture (Fig. 4).

Table 2. South and Central Asia: Change in Agricultural Land (1993-2002)

Country |

1993 Hectares (000s) |

2002 Hectares (000s) |

Change |

|

Hectares (000s) |

Percent |

|||

Afghanistan |

8054 |

8054 |

0 |

0 |

Bangladesh |

8234 |

8429 |

195 |

2.3 |

Bhutan |

135 |

165 |

30 |

18.2 |

India |

169737 |

170115 |

378 |

0.2 |

Iran |

18882 |

17088 |

-1794 |

-10.5 |

Maldives |

8 |

12 |

4 |

33.3 |

Nepal |

2573 |

3294 |

721 |

21.9 |

Pakistan |

21400 |

22120 |

720 |

3.3 |

Sri Lanka |

1880 |

1916 |

36 |

1.9 |

Kazakhstan |

35185 |

21671 |

-13514 |

-62.4 |

Kyrgyzstan |

1420 |

1411 |

-9 |

-0.6 |

Tajikistan |

998 |

1057 |

59 |

5.6 |

Turkmenistan |

1513 |

1915 |

402 |

21.0 |

Uzbekistan |

4848 |

4827 |

-21 |

-0.4 |

South and Central Asia |

276860.0 |

264076.0 |

-12784 |

-4.8 |

Asia Pecific |

559839 |

575975 |

16136 |

2.8 |

World |

1515810 |

1540708 |

24898 |

1.62 |

Fig. 4. Land Use vs. Agriculture Population in South and Central Asia , 2002.

Overall land use pattern (Fig 5) is a reflection of physical and socio-economic factors. For example, a large area has been classified as ‘other lands’ throughout the regions, which is a result of hilly or desert terrain with unfavorable agro-ecological conditions as well as extensive built up areas in countries with high density of population.

The human pressure on arable land in countries of the regions is quite heavy. The average per capita available arable land in South and Central Asia is 0.3 hectares, compared to 0.6 hectares for the world and 0.3 in Asia and the Pacific. Figure 5 indicates the pressure on agricultural land in countries of the regions.

Despite minor addition annually to the existing land under plough, pressure on land resources in the regions particularly in South Asia is increasing (Fig. 6). Historically there has been an increase in person to arable land ratio because the population has been growing faster than agricultural land. The problem has been compounded in some countries of the regions, such as Bangladesh, India and Pakistan by land fragmentation, which has reduced the size of landholdings. This has contributed to reduced agricultural efficiency and hence the overall productivity of the land. Therefore, besides expansion of agricultural land, other avenues had to be explored and adopted. A major mean that has been employed to increase productivity particularly during Green Revolution has been enhanced use of agrochemicals and other inputs. In fact, Green Revolution brought major structural transformations in agriculture within the regions as discussed in the next section.

Fig. 6. South and Central Asia: Percentage Change in Agricultural Land vs. Agricultural Population 1992 -2002

Major Structural Transformations in Agriculture

Agriculture in the South and Central Asian regions has undergone major structural transformation in the past fifty to sixty years. Beginning about the middle of last century, the accelerated use of agrochemicals has been the engine powering the growth in the regions agricultural outputs. The contribution of irrigation has been no less important in reclaiming land for agriculture. The input of improved seeds (high yielding varieties) and mechanization has also boosted the agricultural productivity. This transformation and the new management practices particularly during the Green Revolution and its aftermath have no doubt helped in alleviating hunger from many countries of the regions. Nevertheless they have also had adverse impact on the ecological and genetic resources base in the process. A vast body of literature exists on the beneficial and adverse impacts of Green Revolution.

In the South and Central Asian Regions, high yielding seed varieties along with chemical fertilizers, and intensive agricultural practices, were the principal factors, which brought the ‘Green Revolution’. With growing intensification, the application of chemical fertilizer increased dramatically in the regions. However, in recent years only four countries in the regions exceeded the average consumption of fertilizer in the world namely Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Uzbekistan, and the same also exceeded Asia-Pacific. Bangladesh uses the most fertilizer per hectare in the regions, exceeding 169 kg/ha, followed by Sri Lanka and Uzbekistan, both with about 148 kg/ha. Pakistan trails next with 134 kg/ha (Fig. 7).

While mineral fertilizer consumption enhanced in most South Asian countries over 1993-2002 period, they declined in all Central Asian States with the exception of Uzbekistan, where mineral fertilizer consumption has shot up by almost 5 per cent annually as shown in Fig. 8. Historically increased application of mineral fertilizers has contributed significantly to increased agricultural production in the regions. For example, cereal yields, that dominate agricultural production in the regions, have increased substantially. However, recent data shows diminishing returns from sustained fertilizer application in South Asia (Fig. 8). It can be seen that although fertilizer application rates have increased significantly in the South Asian countries, commensurate increases in crop yields have not always been achieved. .

The intensification of fertilizer use has also been accompanied by extensive use of pesticides (herbicides, insecticides and fungicides). While contributing to enhance production, they have also posed risks to farmers’ health, through contact during application. In addition they have found their way into human body by contaminating the water supply and entering food chain. Pesticides and other agrochemicals application was encouraged through subsidies, tax incentives and agricultural extension programmes during Green Revolution. Consequently, pesticide application extended to a variety of cereals, cotton, sugarcane and plantation crops. “In India alone, treated acreage expanded from less than 6 million hectares in 1960, to over 80 million hectares in the mid 1980s. Pakistan and Sri Lanka also increased their consumption by more than 10 per cent per year for the period 1984-88. Along with pesticide imports, the indigenous production of pesticides increased. For instance, India enhanced its production of pesticides 13 fold between 1970 and 1980 . Basically pesticides are applied to attack certain target organisms or pests. However, they carry potential risk of harming

fig 7 footnote 19

human and many other species of mammals, birds, and fish and insects. They have also poisoned beneficial insects such as bees and other pollinators and birds that feed on contaminated food.

* Data for Afghanistan, Bhutan and Maldives is not available.

Fig. 8 South and Central Asia: Growth in Fertilizer Application and Cereal Yield

Irrigation has also played an important role in boosting agricultural production. Irrigation is by far the largest consumer of water in the regions accounting for over two thirds of water abstracted from the rivers, lakes and aquifers. Irrigated area constitutes some 39 per cent of the cropland compared to about 10 per cent in the world and 32 per cent in Asia and the Pacific. Amongst countries, barring Kazakhstan, in all other Central Asian states over two third cropped areas are irrigated. In South Asia, 80 per cent of cropland in Pakistan is irrigated, while in Bangladesh over half of the cropland is under irrigation. Of the total irrigated area in the regions, about three fourth is in South Asia (Fig.9). In Central Asia, Uzbekistan alone accounts for over half of the irrigated area in the sub regions. Amongst others, three countries including India, Pakistan and Bangladesh account for over three fourth irrigated area of the regions (Table 3). The expansion in irrigated area has declined considerably over time due to water shortages. On a regional basis, irrigated area in the regions expanded by an average of 1.1 per cent per year compared to 0.9 percent in the world and 1.2 per cent in Asia and the Pacific. Among countries, largest growth in irrigated area was in Bangladesh followed by Sri Lanka and India respectively. In majority of other countries annual growth rate of irrigated area was 0.6 per cent or less (Table 3).

Fig. 9. South and Central Asia: Ratio of Irrigated to Cultivated Land 2002

In fact, water is becoming a limiting factor in agriculture due to increased intensity of cropping as well as diversion of water to non-agricultural uses. Another contributing factor is transmission losses, primarily as a result of seepage from the canals and distributaries and wastage due to lack of appropriate and realistic price mechanisms. It may be noted that Repetto as far back as 1980s estimated that subsidies to irrigation in six Asian countries accounted for as much as 90 per cent of the total operating and maintenance costs. This kind of market distortion, no doubt leads to wastage of a very big chunk of water diverted or pumped for irrigation. While reducing the quantity of water available for irrigation, transmission losses through seepage have created the problem of water-logging and salinity, which have affected a vast tract of land in the regions. The other ways in which farming activities have harmed land include soil erosion through expansion of farming into marginal lands; and reduction in soil fertility through loss of nutrient as a result of monoculture and heavy application of nitrogenous fertilizers.

Table 3 South and Central Asia: Expansion in Irrigated Land 1993-2002

Country/Area |

Irrigated land 1993 Hectares (000s) |

Irrigated land 2002 Hectares (000s) |

Annual growth (%) |

Afghanistan |

2400 |

2386 |

0 |

Bangladesh |

3252 |

4597 |

4.1 |

Bhutan |

39 |

40 |

0.3 |

India |

50101 |

57198 |

1.5 |

Iran |

7264 |

7500 |

0.5 |

Maldives |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Nepal |

1050 |

1135 |

0.6 |

Pakistan |

17120 |

17800 |

0.6 |

Sri Lanka |

550 |

638 |

2.0 |

Kazakhstan |

2250 |

2350 |

0.5 |

Kyrgyzstan |

1050 |

1072 |

0.1 |

Tajikistan |

718 |

719 |

0 |

Turkmenistan |

1600 |

1800 |

0.9 |

Uzbekistan |

4250 |

4281 |

0 |

South and Central Asia |

91644 |

101516 |

1.1 |

Asia Pacific |

165029 |

181703 |

1.2 |

World |

256568 |

276719 |

0.9 |

Excessive diversion of water from both surface and underground sources has caused very serious problems. The Aral Sea disaster is a classical case in point whereby the diversion of water from Amu and Sir Darya has caused the drastic shrinkage of Aral Sea with very serious economic, environmental and social consequences which are well documented in literature elsewhere , , , , Overdraft from underground aquifers through tube wells has also posed serious problem. For example it has led to drying of Karezes or underground channels in Baluchistan province of Pakistan.

Among other inputs, High Yielding Varieties (HYV) of crops, were the prime movers of Green Revolution. They spread very quickly and “by 1970, about 20 percent of the wheat area and 30 percent of the rice area in developing countries of the world were planted to HYVs and by 1990, the share had increased to about 70 percent for both crops”.

In South and Central Asia, as elsewhere in the world, the propagation and heavy reliance on a few major high yielding cereal varieties promoted monoculture and led to loss of biodiversity on farms. For example one single variety of wheat blanketed 67 per cent of wheat acreage in Bangladesh in 1983 and 30 per cent of wheat acreage in India in 1984. Likewise, in India, according to one study ten rice varieties were expected to cover an area, which at one time had been growing over 30,000 . Such drastic reduction of agricultural biodiversity means fewer options for ensuring more diverse nutrition, enhancing food production, raising incomes, coping with environmental constraints and sustainably managing ecosystems . Another serious aspect of this problem is that along with the loss of agricultural biodiversity, the erosion of the traditional knowledge and skills of indigenous peoples has occurred. This indeed is a very significant loss of depository of knowledge because these people selected, bred and cultivated the diverse varieties of crops over thousands of years.

It has been pointed out that the Green Revolution also had social impacts in terms of increased income inequality, inequitable asset distribution, and worsened absolute poverty. Literature on how agricultural technological change affected poor farmers has been reviewed elsewhere , , , . However, in summary, the critics of the Green Revolution argued that the main adopters of new technologies were the owners of large farms; being rich; they had better access to irrigation water, fertilizers, seeds, and credit. In contrast “small farmers were either unaffected or harmed because the Green Revolution resulted in lower product prices, higher input prices, and efforts by landlords to increase rents or force tenants off the land. Although a number of village and household studies conducted soon after the release of Green Revolution technologies lent some support to early critics, more recent evidence shows mixed outcomes” . Nevertheless these studies and their results “led to the recognition by development agencies, including FAO, of the need to formulate a more equitable and sustainable Green Revolution, aimed at improving food security for the hard-core poor in rural areas”. No doubt, some of the adverse outcomes of the green revolution were inevitable in the wake of millions of farmers using modern inputs for the first time without a sound knowledge of their application and side effects. However, inadequate extension and training, and such flaws in government policies as absence of effective regulation of water quality and input pricing as well as subsidy policies were also responsible for these outcomes.

The above analysis point out that in the post Green Revolution era, agriculture continues to offer great promise for growth, food security and poverty reduction particularly with the new opportunities provided by the developments in the science of crop genetics that are leading to new Genetic Revolution. However it still faces numerous challenges, which need to be addressed appropriately, if sustainable benefits are to be reaped from modern agriculture in the regions.

Emerging Challenges

Agriculture in South and Central Asia in the new millennium faces several challenges. The most prominent among these are challenges related to policy and investments, natural resources, technology and climate change.

5.1 Policy and Investments:

The most daunting challenge to agriculture in South and Central Asian countries is to formulate and implement effective and responsive integrated policy frame-works with appropriate investments in agriculture. Whether it is the problem of increasing water scarcity or degradation of land resources (water logging and salinity); inefficient use of agricultural inputs (specially unbalanced application of fertilizer and inefficient water application) or ineffective transfer of technology to the farmers; lack of coordination between research and extension, or post harvest losses, in one way or another they are related to policy formulation and implementation. For example subsidies or “Price support schemes are often preferred by politicians,” noted the World Bank in its recently published special report on Agriculture for Development . The reason is that the “benefits from public investments in agricultural productivity, such as agricultural research and development and rural infrastructure, are less immediate, less visible and thus less appealing to policymakers” . For example in India, out of the total public expenditure in agriculture, subsidies took up as much as 75 percent, while investments accounted for only 25 per cent. Although according to International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), “The return on investment is 5-10 times more than the return on subsidies”

Agricultural investments have also been low in developing countries including those of South and Central Asia. For example public spending on agricultural research and development averaged 0.4 percent of Asia’s agriculture gross domestic product in 2000, compared with 2.36 percent in high-income countries . Director General of FAO has already expressed concern that governments all over the world were not paying adequate attention to investment in agricultural and allied technology. International development agencies such as the World Bank are also partly to blame for the recent drought in public investments for boosting Asia’s agricultural productivity. According to United Nations, official development assistance for agriculture fell by 57 percent in Asia between 1983 and 2000 . This is a matter of concern particularly because agriculture played a major role in transforming economies of such countries in the regions as India. It “contributed an average seven percent to growth in GDP between 1995 and 2003, though the sector contributes only about 13 percent to the economy and employs just over half of the labor force.” .

Institutional reforms, involving reform of land tenure systems and provision of credit facilities to small farmers are also key actions which are required in the agriculture sector. It has been shown that secure tenure ship encourages farmers to practice sustainable land management, whereas the absence of any land rights only promotes short-term exploitation and subsequent land degradation. For example in India, there is strong evidence that where land is owned by the farmer, land prices reflect conservation efforts thus providing a real incentive for sustainable management . Unsecured tenure can also deprive farmers to obtain credit for land improvements, since they can offer no collateral. According to International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), 450 million farms, or 85 percent of the world’s total, measure less than two hectares and have the potential to increase food production if they receive long-term help . South and Central Asia is no exception. In order to improve the productivity, profitability, and sustainability of smallholder farming, the World Bank recommends a broad array of actions such as improving price incentives and increasing the quality and quantity of public investment; making product markets work better; enhancing the performance of producer organizations; promoting innovation through science and technology and improving access to financial services and reducing exposure to uninsured risks . The last measure could particularly be effective to check the large number of farmer suicides in India, due to crop failure. The recent cold wave in north India had ruined up to half the vegetable crop in Punjab, “but hardly any of the farmers had insurance”.

5.2 Natural Resources:

The gravity of challenge to natural resources for agriculture is clear from the fact that the countries of South and Central Asia will need to produce more food for their growing population in future with reduced natural resources such as land and water per capita. Availability of land is being reduced both by non availability of new lands as well as degradation of existing land in both irrigated and dry land or rain fed areas. The critical shortage of land for further agricultural expansion has already led to increasing intensification of inputs for achieving higher yields. In irrigated areas, it has resulted in water logging and salinity due to unwise use of water. Widespread monoculture and excessive and unbalanced use of agrochemicals have exacerbated land degradation. In dry land/rain fed areas, mining of soil nutrients, erosion and deforestation are to be blamed for land degradation. It is therefore imperative to check agricultural subsidies, establish appropriate water charges to manage demand, define standards for irrigation efficiency and implement agro forestry projects to reduce erosion of soil. Similarly, there is a need to encourage integrated pest management and nutrient management to reduce the use of pesticides and fertilizers. Development of national land use plans and preparation of guidelines on the appropriate use of land resources commensurate with land potential could also pay the dividend.

Water shortages and water scarcity are looming over the regions. Since large new demands for irrigation in future will not be available, hence new strategies would need to be explored. Supply-side approaches to the challenge of sustaining the water system to the increasing demand includes such technological innovations in irrigation systems as laser land leveling, furrow irrigation and high efficiency irrigation systems (drip & sprinkle), instead of extravagant gravitational irrigation. New breeds of crops that require less water, conservation and water reclamation would also need to be introduced. Additionally, the potential for increasing the role of dry land/ rain fed agriculture and rehabilitating presently degraded land would need to be explored. It has been estimated that in Pakistan alone, developing drought-tolerant and water-use efficient crop varieties through biotechnology will help in reclamation of nearly 14 million acres of salt affected waste land and large areas of sandy desert through an integrated approach .

Conservation of biodiversity in terms of genetic resource preservation is another major challenge to sustainable agricultural production and attaining food security. With the advances in genetic engineering, biodiversity is becoming an important resource for sustainable development. However, as discussed earlier, a disturbing consequence of Green Revolution is the species loss and genetic erosion of agricultural biodiversity. While there are no easy solutions to the complex problems of biodiversity conservation, the great challenge that countries of the regions must confront is the scientific management of their genetic resources and the assertion of property rights over these resources and to negotiate skillfully under biodiversity convention to facilitate the equitable sharing of benefits of biotechnology between the developed and developing countries.

5.3 Technology

In the wake of dwindling resources, it is a big challenge for the countries of South and Central Asia to support their growing population with current technology and practices alone. Reaping the benefits of ‘Gene Revolution,’ in biotechnology can help in increasing production with better resistance, and lower costs of production. South and Central Asia has entered this sector by developing transgenic cotton varieties which will drastically reduce use of pesticides.

Nevertheless, reaping the full benefits of the ‘Gene Revolution’ demand resolution of several issues related to intellectual property rights. Internationally, most of the current agro -biotechnology research is being undertaken by a few multilateral companies which basically cater to the interests of rich farmers and developed countries. Unlike Green Revolution, the new technology is not being freely available to end-users. This demands not only intensification of research in public sector but also encouragement to private sector in South and Central Asia to move into this promising field. Initially, however, the public sector will need to play the major role in ensuring that small and disadvantaged farmers and resource poor areas, that lagged behind in Green Revolution are not left further behind by the upcoming ‘Gene Revolution.’ This creates the need to establish centers especially on agro - genomics to act as the supplier of all basic information for developing desirable transgenic crops and animals . Investments in this area is expected to give high rates of return and without such investments, many countries may continue to lose ground in the ability to adapt new knowledge and technologies developed elsewhere and ensure competitiveness .

5.4 Climate Change

The challenge of the climate change to agriculture is now unambiguous. However, its “exact magnitude is uncertain because of the complex interactions and feedback processes in the ecosystem and the economy. Five main factors will affect agricultural productivity: changes in temperature, precipitation, carbon dioxide (CO2) fertilization, climate variability, and surface water runoff”. Besides rise in temperature, the region is likely to witness a shift in both intensity and timing of the monsoon season, which could result in heavy losses to national economies in South Asia. In agricultural sector, the direct impacts would be on crop yields and food security. In addition, indirect effects on agricultural production will be through climate change impacts on availability of water resources, biodiversity, energy and frequency and intensity of natural disasters. It is important, therefore not only to understand, but also to adapt to and mitigate the impact of the climate change. As a first step towards that end, comprehensive and careful studies would be needed to understand the nature and the extent of climatic change in the countries of the regions. It would also be important to develop plants and farming systems, which are less vulnerable to such changes. Understanding the impacts on crop yield, their geographical distribution, vulnerability to pests and increased climate related disasters will be particularly important.

Undeniably, the poor in the regions will be most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change because of their overwhelming dependence on agriculture and their lower capacity to adapt. Such poor farmers with severe resource constraints may need help from outside, especially where costs of adaptation are higher. In these cases, “the public sector can facilitate adaptation through such measures as crop and livestock insurance, safety nets, and research on and dissemination of flood-, heat-, and drought resistant crops. New irrigation schemes in dry land farming areas are likely to be particularly effective, especially when combined with complementary reforms and better market access for high-value products. However, greater variability of rainfall and surface flows needs to be taken into account in the design of new irrigation schemes and the retrofitting of existing ones”.

Conclusion

Although the overall share of agriculture in South and Central Asia has declined in the past, it still remains the mainstay of the economies in the regions. The major challenge facing development in agricultural sector is the problem of reconciling its growth while minimizing the adverse environmental impacts of intensive cultivation practices. Agricultural production in the regions has increased substantially over the past fifty years contributing positively towards food security. However, the growth in food has only just kept pace with the growth in population; as a result net benefits have been neutralized.

Agricultural growth and development in the regions can be traced in three phases. In the first phase, the growth was attained primarily by the expansion of croplands into forest and other land uses. For instance, in South Asia alone over 60 million hectares of forest was lost to croplands between 1850 and 1960. The next phase starts with the dawn of Green Revolution, when the expansion of agricultural land continued with the intensification of farming. Present agricultural policy in most countries of the regions are geared towards the goals of the ‘Green Revolution’, i.e. increasing yields through optimization of resources, research and development in agricultural practice and providing credit and support to farmers. However, indiscriminate use of inputs such as agrochemicals and water encouraged during early period of Green Revolution to increase yields resulted in substantial environmental damages. Subsidies provided on agricultural inputs resulted in market distortion and excessive and wasteful use of water, diminishing rates of return on fertilizer and pesticides application, land degradation, as well as water scarcity and environmental pollution. It is clear that the long-term mitigation of the environmental impacts of farming in the regions will only be achieved by a substantial review of agricultural policy and its sustainability. The agricultural sector looks set to change significantly in years to come with the development of global market economies. The issue of agricultural subsidies is already receiving close attention, with the tendency being to do away with food subsidies, water subsidies and the like, and only implement them in the event of natural disasters, such as famine or flood. Along with these steps, strong initiatives are also needed on the provision of security of tenure, strengthening of organizations for small farmers and the involvement of user’s groups and communities in the operation and maintenance of irrigation systems.

The critical shortage of land and water for further agricultural expansion in the regions can be witnessed from very limited expansion in total crop and irrigated land during the last fifteen years. The pressure on land is acute in the wake of limited cultivated land per capita. With increasing resource constraints, a major challenge for the countries in the regions is to explore the potential of new technologies to support their growing population. The advent of Gene Revolution provides an opportunity for the same. The regions have already entered the third phase of agricultural development with the introduction of transgenic cotton. Reaping the full benefits of ‘Gene Revolution’ in biotechnology can help the regions in increasing agricultural yields with better resistance to diseases, in meeting the exigencies of climate change, and reducing the costs of production. However, unlike Green Revolution, the new technology of Gene Revolution is not freely available to end-users due to intellectual property rights, and monopolization of transgenic by multilateral firms. This demands not only intensification of research in public sector but also encouragement to private sector in the regions to move into this promising field. It is also important for the public sector to ensure that small and disadvantaged farmers and resource poor areas, that lagged behind in Green Revolution are not left further behind during the upcoming Gene Revolution.

In conclusion, the role of agriculture as an economic activity and as a source of livelihood can hardly be overemphasized in the South and Central Asian regions. Coupled with the recent food crisis it has led the governments across the regions as well as donors to realize that agriculture still constitutes a very significant part of the development agenda. Moreover studies have shown that agriculture has very important role in reducing rural poverty and hence in providing high dividend towards achieving target of halving the number of poor under the Millennium Development Goal. South Asia, which contains 600 million poor of the regions, arguably has the most to gain by improving its agricultural productivity. Agriculture also offers a window of opportunity for addressing environmental concerns in the wake of growing resource scarcity, looming threat of climate change and dwindling biodiversity in the regions through an integrated policy framework most suited to each country’s economic and social conditions. Realizing the potential of agriculture for development agenda in the regions, however, requires the prominent role of the state in terms of improving the investment climate, regulating natural resource management, providing core public goods, and securing desirable social outcomes.

Bibliography

Ashirbekov. U., Zonn, I., (2003), Aral: the History of Sea Disappearance, Dushanbe, Tajikistan (In Russian).

Bissell, T, (2002), Eternal Winter: Lessons of the Aral Sea Disaster, Harpers, pp 41-56.

- Brandon C. and Ramankutty R. (1993). Towards an Environmental Strategy for Asia. World Bank, Washington D.C.

DPA (2008), Food crisis a wakeup call for Asian Agriculture,http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/world-news/food-crisis-a-wakeup-call-for-asian-agriculture_10072025.html Accessed January 2009.

Ellis, W.S. (1990), A Soviet Sea Lies Dying, National Geographic, February, pp, 73-93.

- Evenson, R. E, and Gollin, D. (2003), “Assessing the Impact of the Green Revolution, 1960 to 2000” Science, sciencemag.org ,Vol. 300. no. 5620, pp. 758 – 762, 2, May.

- FAO (2005), Selected Indicators of Food and Agriculture Development in Asia-Pacific Regions 1994-2004, RAP publication 2005/20, Bangkok.

- FAO, (2008), Erosion of Plant Genetic Diversity, http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/focus/2004/51102/article_51107en.html). Accessed February 2009.

- FAO, (no date), Women and Green Revolution, http://www.fao.org/focus/e/women/green-e.htm Accessed January 2009.

- Fowler, C. and Mooney, P. (1990). Shattering: Food, Politics and the Loss of Genetic Diversity, University of Arizona Press, Tuscon.

Glantz, M. H. (1999), Creeping Environmental Problems and Sustainable Development in the Aral Sea, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Gopal, K., (2004), Poisoned and silenced by pesticides, Toxic Links, http://www.toxicslink.org/art-view.php?id=3) Accessed June 2008.

- Government of Pakistan (2007). Vision 2030, Planning Commission, Islamabad.

- Hazell, P (2003) Green Revolution :Curse or blessing, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington DC.

- Hazell, P., and Haddad. L, (2001) Agricultural Research and Poverty Reduction.

ICT, (2008a), More investment in farming vital to Indian economy http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/business/more-investment-in-farming-vital-to-indian-economy-world-bank_10017886.html Accessed January 2009.

ICT, (2008b), UN body for urgent steps to counter rising food prices,http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/business/un-body-for-urgent-steps-to-counter-rising-food-prices_10036134.html Accessed January 2009.

- IFPRI-International Food Policy Research Institute (2002), Green Revolution: Curse or Blessing? Washington DC., U.S.A.: John Hopkins University Press for IFPRI.

Nguyen, J. T. (2008), UN seeks agriculture renaissance while fighting food crisis http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/world-news/un-seeks-agriculture-renaissance-while-fighting-food-crisis_10052438.html, Accessed December 2008.

- Repetto R. (1986). Skimming the Water: Rent Seeking and the Performance of Public Irrigation System, Research Report No. 4, World Resources Institute, Washington D.C.

- Reppeto, E and Gillis, M. (1988), Public Policy and Misuse of Forest Resources, Cambridge.

- Ryan, J.C. (1992), “Conserving Biodiversity” in Brown, L.R. et al, State of The World 1992, New York. Asian Development Bank, 2000.

- Tilman. D, (1998), The greening of the green revolution, Nature 396, 211-212, 19 November.

United Nation (2006) World Population prospects: The 2006 Revision, New York, USA.

- United Nations (1995), State of the Environment in Asia and the Pacific, Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok.

- World Bank, (2008), World Development Report 2008, Washington DC.

* Professor (HEC), Institute of Geography and Urban Regional Planning, University of Peshawar

** Associate Professor, Institute of Geography and Urban Regional Planning, University of Peshawar.

“This implies misapplication, as would seem to be evident from the high levels of nutrient pollution found in many of the regions’ inland and estuarine waters. Due to unbalanced use of nitrogen based fertilizers, in particular, besides lost soil fertility, pollution of environment has occurred through nitrate leaching, emission of gaseous nitrogen, and the vitalization of ammonia. Whilst contamination of the regions’ water sources is by far the most significant impact, the release of nitrogen based gases and ammonia have also contributed to both the greenhouse effect and to the depletion of the earth’s ozone layer” (United Nations 1995)

“Every year, about 3 million people are poisoned around the world and 200,000 die from pesticide use. Beyond the reported acute cases of pesticide poisoning, the chronic long-term effects such as cancers are even more worrisome. There has also been increasing evidence and concern over pesticides that mimic natural hormones (known as endocrine disruptors), possibly causing a wide variety of adverse effects -- not only on specific body organs and systems but also on the endocrine systems which include reduction in male sperm count and undescended testes as well as increasing incidence of breast cancer” (Gopal, 2004).

Such “problems are slowly being rectified without yield loss, and sometimes with yield increases, thanks to policy reforms and improved technologies and management practices, such as pest-resistant varieties, biological pest control, precision farming, and crop diversification” Op cit.

“The global planting of transgenic crops is rising annually at a rapid rate from 1.7 million ha in 1996 to 81 million hectares in 2004. By the end of 2004, transgenic crops were grown in several developed and developing countries; but two-thirds of the world’s transgenic area and more than 90 per cent production is located in developed counties” (Government of Pakistan,2007)