Central Asia Journal No. 67

An Image of Foreignness:

The German-Austrian Alpine Club and its 1913 Turkestan Expedition

Kurt Scharr*

The Alpine Club’s Turkestan expedition of 1913 marks the beginning of the club expanding its field of exploration beyond the European Alps. At that time the German-Austrian Alpine Club (Deutscher undÖsterreichischerAlpenverein) was already one of the world’s largest and most influential private Alpine organisations. This adventure drew not only the most experienced expedition leaders, such as the Alpinist and descendant of a well-known ship-owner family, Willi R. Rickmers, but also leading scientists of the time from the Austrian universities of Innsbruck and Graz (e.g. the later professor of Geology in Innsbruck, Raimund v. Klebelsberg) (see Fig. 1). As one important result of this expedition, Klebelsberg published a remarkable study on the geology of western Turkestan. Unfortunately the Great War delayed publication until 1922. These explorers not only initiated a lasting tradition of expeditions abroad, organised by the Alpenverein, but they were also the first to explore this region from a Central European point of view. In 1928 a German-Soviet expedition, again organised by the Alpenverein, targeted this area – although under completely different political circumstances, eventually followed in 1975 by another effort of the Austrian Alpenverein.

Fig. 1. Scientists and natives. “Ficker and Klebelsberg 1913. In the Middle a Tadshik, to the right a Usbek.”Rickmers (1930), Alai-Alai, 16.

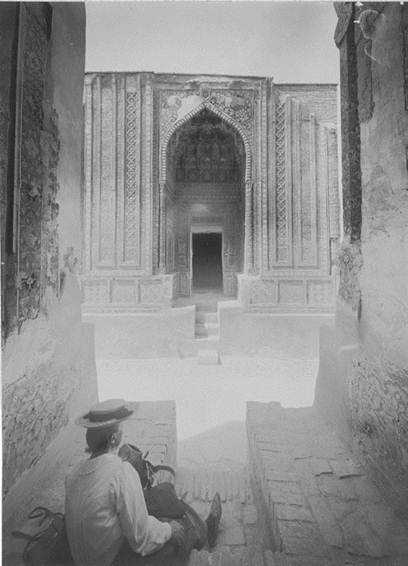

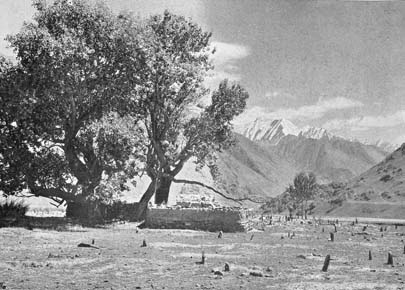

The rich scientific returns of this first Turkestan expedition, although an integral part of the Alpenverein’s initial remit, reflect only some of its achievements. Exploring the rich geographical and historical culture of Middle Asia from a Central European point of view definitely shaped the image of this region as a ‘country of Turcs’ in European minds: the wild untouched nature and the exotic culture of the native population, both welcoming the foreigners (see Fig. 2).

The archives of the Alpenverein in Innsbruck (Austria) and Munich (Germany) not only possess written records of its very first expedition beyond the Alps but also a wide range of photographs, which together document the researchers’ perspective towards Turkestan at the beginning of the 20th century. These records help to analyse and to question the main characteristics of the constructed image of Middle Asia and its persistence in a longue durée. At the same time this analytical contribution to Western imagology of ‘Turkestan’ is meant to establish the starting point for further discussions and scientific exchanges based on these little known records.

Fig. 2. European nostalgic space Turkestan. “Orient. Basar in Bokhara”. Borchers (1931), Berge, 1.

Introduction by Two Images

Image 1

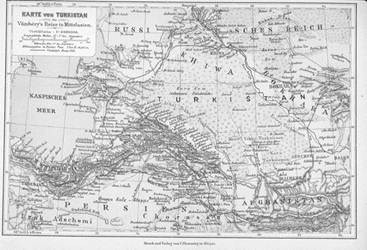

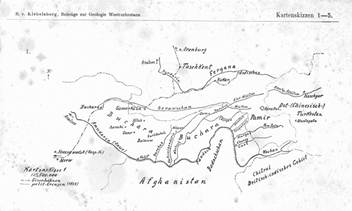

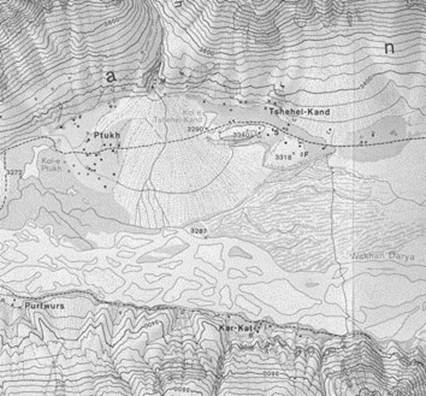

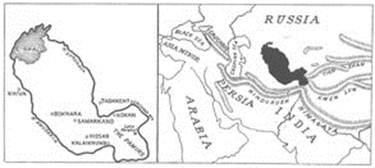

The “Map of Turkistan” by Hermann Vámbéry (Fig.3), an Hungarian orientalist and Turkologist, shows the route of his expedition at a time, around 1863, when the Russians were still in the process of conquering the area. Vámbéry identifies settlements of several Turkmen groups. Central to this map are supposedly sparsely inhabited areas of the Kara-Kum desert. Denser settlement patterns run along the mountain ranges at the edge of the desert. The second map applies a much bigger scale (Fig.4/5). It is a section from the general map for the expeditions of the D.u.Oe.A.V. of 1913 and 1928. It was produced by the Alpenverein, a key player in the cartography of that time. The paper discusses the eastern edge of historic “Western Turkestan”. Here areas of great cartographic detail around the Peter the Greatmassif in north-western Pamir, measured and named, are confronted in contemporary maps with empty unexplored space, where worm-shaped mountain ranges separate the valleys. Both maps identify, in method and symbolism, the region that is the theme of this paper. In terms of method, the scale alternates between large areas in small representation of low substantive resolution with small areas depicted with a high density of information (a thick narrative) (Fig. 6). In terms of symbolism, both examples delineate the incremental conquest of this region, from the plains of the desert to the verticals of the mountain ranges.

Fig. 3. “Map of Turkistan.” H. Vámbéry 1863. Collection K. Scharr.

Fig. 4. General map of D.u.Oe.A.V.’s expedition 1913. Klebelsberg (1922), Geologie. Kartenskizze 6.

Fig. 5. Map supplement 2, report of Alai-Pamir-Expedition 1928, sketch R. Finsterwalder. Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Hg.) (1929), Alai-Pamir.

Fig. 6. Part of Koh-e-Pamir map Austrian Alpine Club 1975. deGrancy(Hg.) (1978), Anhang.

Image 2

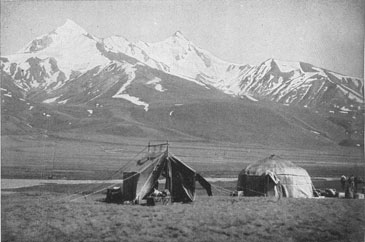

Three photographs and one diagram, produced between 1906 and 1988 (Fig.7-9). In their sequence and their deeper meaning, they represent a chronotopos . From a European perspective, these images of ‘Turkestan’ condense discovery, exploration, construction and projection of a place of longingin its longue durée. On closer inspection it is possible to perceive in them an inner relation between space (Turkestan) and narrative (image of Turkestan) that I want to discuss below.

Fig. 7. Mabel Rickmers in front of Shah iZinda, Samarkand (dated 1896-1913), today Usbekistan. Alpenarchiv D.A.V. NAS 1 FF/582/0.

Fig. 8. “The High Valley of Tuptchek (…) In front the camp of the Alpine’s Club expedition from 16 to 20 July 1913”.v. Klebelsberg (1922), Geologie, Abb. 15.

Fig. 9. Original book cover Alai-Alai!, front page. Rickmers (1930), Alai-Alai! Alpenarchiv D.A.V. 04. 01. 1965, 1601.

- Turkestan as canvas

While Vámbéry’s expedition, a few years before the establishment of the Russian General General gouvernement Turkestan in 1867, still had the feel of an adventure journey, the numerous expeditions around the turn of the century increasingly aimed at exploring specific areas. Willi R. Rickmers (1873-1965), descendent of German ship-owners and Tyrolean tourism pioneer, alone carried out five such expeditions before 1913 (1894, 1895, 1896, 1898, 1906), accompanied on some of these by his wife Mabel (1866-1939), a British orientalist. His endeavours were still dominated by a desire for discovery, a lust for adventure and a romantic outlook expressed in stereotypical terms, such as ‘New World’, ‘Orient’ and ‘wilderness’. The search for ‘original’ and ‘virgin’ places was paramount. His descriptions betray the nostalgia of the traveller, which can often be interpreted as a response to the disorientation caused by the bewildering pace of progress in his own society. Cenci von Ficker (1878-1956), one of the participants of the expedition of 1906 describes her farewell from Turkestan and its mountains in melancholic terms, rather like a last sunset: “We returned on the large caravan route that links the traffic of the rich Beks at the edge of the mountains with Samarkand and Bokhara. These were days of magnificent riding, early in the azure scent of an autumn morning, and late in the deep luminance of the earnest evening steppe. Soon the mountains were at our back, then alongside us and became drawn-out uplands, then flatter and eventually petered out. In the end it is just the steppe making waves and mingling in the south, gray and uniform, with the horizon.”

‘Turfan’ research, and especially the expeditions organised by the German Ethnological Museum in Berlin in 1902 and 1914, greatly contributed to substantiating the cultural studies notion of the ‘Silk Road’ and the (re)construction of an historical region and its relational networks. The Turkestan expedition of the D.u.Oe.A.V., in 1913 must be seen in its contemporary context of the search for lost languages and forgotten worlds. In the alpinist exploration of the vertical aspect , the European spatial ascriptions of the Orient merged with the blank spots on the map and the high mountains as ‘virgin’ and therefore ‘romantic’ place of specific longings. Rickmers wrote about it in the journal of the Alpenverein (which, at the turn of the century, had more than 80,000 members in the German-speaking countries – which says something about the enormous impact of this publication): “It fairly teemed with long mountain ranges, mysterious glaciers and countless peaks (…) one may safely say that these represented the last large ‘New World’ of Alpinism.”

- Turkestan as Constructed Space

German-speaking geographical research at the turn of the century, in its pursuit of a definitive ordering of the world, was looking for general, timeless, if possible ‘naturally’ arguable criteria for spatial delimitations outside administrative, ‘artificial’ classifications of the modern state. Two attempts deserve to be mentioned in the context of the spatial delimitation and/or the construction of Turkestan. First, there is the approach of Willi R. Rickmers as a result of the 1913 expedition. In the introduction to his book, Rickmers writes: “The Duabasappliedto Turkestan is an innovation which I have chosen for practical reasons (…) This area which I call the Duab contains everything that is typical of and common to various overlapping or subdivided conceptions such as Turkestan”.(Fig.10)

Fig. 10. “The Duab of Turkestan.” Sketch by Rickmers. Geographical situation of Duab. Rickmers (1913), Duab, 2.

Rickmers was well aware that he was about to construct a supposedly homogenous cultural area. In the last instance, the ‘Duab’seemed to him just as artificial as the ‘Alps’ as pretended unity. All the same, Rickmers tried to find objective criteria for his thesis. For him, the Duab, as part of Turkestan, lay between the rivers Amu Darya and Syr Darya and was characterised by the opposition in its natural landscape of dry steppes and deserts on the one hand and glaciated high mountains on the other. For Rickmers the river Zeravshan (Russian Зеравшан) becomes the symbol of cultural landscape dependencies between the mountains in the south-east, rich in water, and the dry areas of the north-western plain. This river, as live link between the cultural centres of Samarkand and Bukhara – before losing itself in the Kara-Kum desert– became the metaphysical image of the Duab itself (Fig.11)

“The Zeravshan is history, history of the landscape, history of mankind. Do you want to hear it, the silent snowflake of conception, the power of solid ice, the thunder of the river birth, the lust of youth, the manly calm stream and the dying murmur! – Then go and listen to the waters of the Zeravshan.”

Fig. 11. “In the Valley of Serafshan.”Ficker (1908), Turkestan, Photo W. R. Rickmers.

In the last instance, Rickmers’ spatial construction is also based on the dominant ‘Orient Romanticism’, which cannot be captured with natural science approaches:„Turkestan was only a town before it became one of the greatest expressions in modern history and geography (…)The Duab is a place with the atmosphere of Turkestan“.

The second attempt at identifying Turkestan in natural landscape is only superficially more objective. The Austrian geographer Fritz Machatschek (1876-1957), a student of Albrecht Penck’s, one of the most influential geographers of the fin-de-siècle) visited the area several times before the First World War and in 1921 published his Landeskunde von Russisch Turkestan based on these travels. Adventure, nostalgia and personal impressions are less prominent with Machatschek. The people and settlements in the photographs become extras and framework for his descriptions of the natural landscape. While Machatschek uses the mountain ranges in the south as ‘natural’ criteria to delimit Western Turkestan as a geographic unit, in the north he moves on to landscape contrasts and the decisive interaction of cultural landscape elements (Fig. 12).The “culture of the oasis territories could not be conceived without the masses of snow in the mountains that enable the rivers to give life where without them there would have to be the silence of the desert”. Consequently he seems to have been aware of the difficulty of physically delimiting Western Turkestan, just as Rickmers was before him, when he writes,“ that the essence of the Orient has to be more felt than it can be defined, Western Turkestan is a real piece of the Orient, in fact, in many ways the Oriental features here still come out in greater purity”.

Fig. 12. “The Borders of Western Turkestan.”Machatschek (1921), Landeskunde, 9.

Even though Machatschek admitted that this spatial delimitation – similar to the Alps – did not exist before for the local population, the fact that the local spatial ascription differed greatly from that of the European explorers was not taken up by contemporary Western European exploration of Turkestan. “Never has this land been understood by its indigenous population as a unit”.

- Occupation and Appropriation of Turkestan

Outwardly delimiting a space initially creates a definable territory, incremental occupation and appropriation follow with measuring and inventorying what is inside. Classic German regional geography as represented by Machatschek in his work on Western Turkestan carries out such systematic spatial description par excellence. Exploratory travels, such as those in 1913 and the German-Soviet Alai-Pamir expedition of 1928, which seamlessly picked up where the earlier one had left off, provided the data to fill in the blank spots inland by and by. Imperial, colonial and postcolonial territorial claims manifested themselves in this type of appropriation.

As early as the 1870s, Fjodorovič Ošanin (1844-1917) , in the course of the ongoing conquest by the Russian Empire, had conceived of calling West-Pamir ‘Peter the Great’ . By exploring the vertical, the later Alpenverein expeditions moved the toponymyon to a larger scale. Geophysicist Heinrich v. Ficker (1881-1957), also participating in the 1913 expedition, suggested a systematic approach. The Romanov mountains should be subdivided into two ranges, that of Peter the Great and that of Catherine the Great. In this way the Russian imperial claim to the territory was inscribed into the mapped landscape. In their representation of the numerous landscape sub-units, the cartographers of the D.u.Oe.A.V., also incorporated local names coined by the indigenous population. The expeditions of1913 and 1928 put down further specific territorial markers. They allow us to deduce contemporary claims of each period as well as ideological links, for instance during the German-Soviet expedition. A few examples: ‘PikSydow’ (Reinhold v. Sydow, long-time chairman of the D.u.Oe.A.V., 1851-1943); ‘PikFicker’ (Heinrich v. Ficker, participant in the 1913 expedition); ‘Finsterwald glacier’ (Sebastian Finsterwalder, 1862-1951, geodesist, developed glaciological photogrammetry); ‘Muschketow glacier’ (IvanVasilevičMušketov, 1850-1902, geologist); ‘Fedschenkoglacier’ (Alexei PavlovičFedčenko, 1844-1873, geographer). In the vicinity of the Fedschenkoglacier there are the highly symbolically named ‘Notgemeinschaftsgletscher’ (‘emergency association glacier’, German Research Association - Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) and ‘Academy glacier’ (Soviet Academy of Sciences). The maps also include ‘German mountain names’ analogous to the Alps, such as ‘Hohe Wand’, ‘Dreispitz’, ‚’Talleit’, ‘Jorasses’, ‘Kalkwand’, etc. (see Fig. 5)

It would be a rewarding and exciting task in itself to systematise these toponymic namings and renamings in the course of the 20th century, both in linguistic terms and in their political statement as a highly visible part of public space.

Conclusion

In the early 20th century, German and Austrian researchers played a key role in the spatial construction of ‘Turkestan’. At the same time these actors found in Turkestan a welcome canvas onto which to project their own fears of loss. These had their roots in frantic modernisation and the structural change that accompanied it, from an agrarian to an industrial society that swept through Europe in the early 20th century. Often this development led to a loss of orientation, to flight and the search for some primitive or untainted place. Some thought, they would find it in the Alps, stylised into spaces where traditional life persisted. The Alpenverein, its officials and members can be seen as driving forces for this narrative. From a European perspective, in addition to the Alps, the Orient and here particularly the ‘historical’ but not identical spaces Turan/Turfan/Turkestan seemed to provide a suitable canvas for such projections.

There were many different approaches to Turkestan. On the one hand, the European but also the Imperial Russian and later the Soviet expeditions all tried to define this space, to order it and thus to constitute and construct it externally. Internally the aim was to inventory its content and thus take it over symbolically as well as physically. On the other hand, and involuntarily, the Europeans discovered in their idea of Turkestan a corrective of their own supremacy claims to the world. European self-assuredness and hegemonial concepts of occidental supremacy took a massive blow as the Oriental high cultures and their long history became better understood.

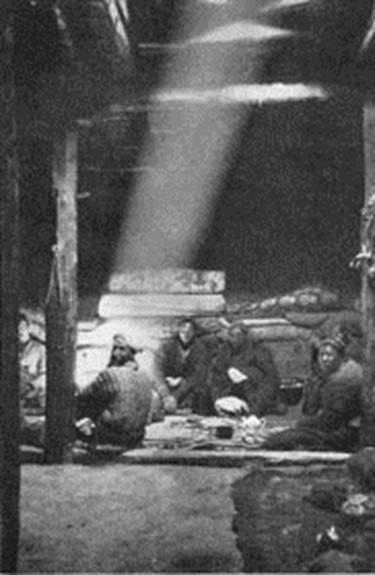

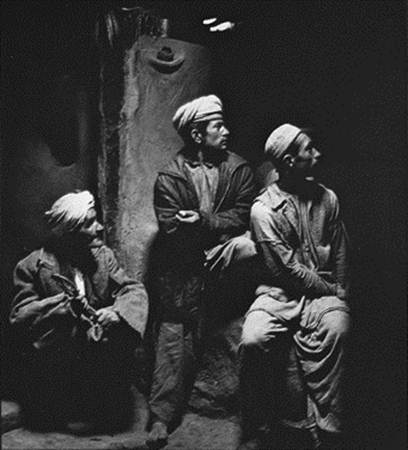

The example of the 1913 expedition of the D.u.Oe.A.V., showcased in this essay, clearly illustrates the contemporary influence of existing images about this area. However, this expedition and its activities and exploration of the high mountains also contributed to changing this European space of refuge for good. Moreover, this expedition documents the ongoing (re)development of older images as well as the reconstruction of the socio-political context of territories. The German-Soviet Pamir expedition of 1928, again led by WilliR. Rickmers, underlines this. Subsequent endeavours (1958, 1975 and 1988) must of course be related to their relevant social context but received substantial influences from the narratives and/or chronotopoi of their predecessors (see Fig. 13-14).

Fig. 13. “Inside a winter house in AltinMasar”. Borchers (1930), Gebirge, Photo 77.

Fig. 14. “Inside a great lounge of a farm building in Selkei”. deGrancy(ed.) (1978), PhotoRaunig, Nr. 54.

Further References

Borchers Philipp & Karl Wien, (1929). Bergfahrten im Pamir. In: Zeitschrift des D.u.Oe.A.V. 60, 64-142.

Borchers Philipp, (1931). Berge und Gletscher im Pamir, Stuttgart.

deGrancyRoger Senarclens& Robert Kostka (eds.), (1978). Grosser Pamir. Österreichisches Forschungsunternehmen in den Wakhan-Pamir/Afghanistan, Graz.

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (ed.), (1929). Die Alai-Pamir-Expedition, 1928. Vorläufige Berichte der deutschen Teilnehmer, Berlin.

Finsterwalder Richard, (1929). Das Expeditionsgebiet im Pamir. In: Zeitschrift des D.u.Oe.A.V. 60, 143-160.

Maurer Eva, Wege zum Pik Stalin. Sowjetische Alpinisten 1928-1953, Zürich.

Rickmers Willi R., (1929). Die Alai-Pamir-Expedition 1928. In: Zeitschrift des D.u.Oe.A.V. 60, 59-63.

Rickmers Willi R., (1930). Querschnitt durch mich, München.

SidikovBahodir, (2002). “Eine unermessliche Region“. Deutsche Bilder und Zerrbilder von Mittelasien (1852-1914), Berlin.

* Privat-Dozent Mag., Dr. Kurt Scharr, Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck, Institut für Geschichtswissenschaften/Geographie, Innrain 52, 6020 INNSBRUCK, AUSTRIA. Kurt.Scharr@uibk.ac.at

Between 1867 and 1917 the area of today’s Turkmenistan, in combination with adjoining areas, was part of the Russian Empire and called General gouvernement Turkestan (from 1886 TurkestanskijKraj). In 1918 this became the Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic of Turkestan. In the years 1924/25 this region was split into several Soviet republics including Turkmenistan. In 1991 Turkmenistan became an independent state.

Cf. Arnberger Erik, Die Kartographie im Alpenverein (Wissenschaftliche Alpenvereinshefte 22), München-Innsbruck, 1970. Aurada Fritz, 100 Jahre Alpenvereinskartographie. Die Alpenvereinskarte und ihre Entwicklung, Sektion Edelweiß des Österreichischen Alpenvereins, Wien, 1962.

BachtinMichail M., Chronotopos, Berlin 2008 (German edition).Бахтин М. М., Формы времени и хронотопа в романе. Очерки по исторической поэтике. Вопросылитературыиэстетики, Москва 1975, 234-407 (first published in Russia).

Rickmers Willi R., Die Berge des Duab von Turkestan. In: Jahrbuch des D.u.Oe.A.V. 39 (1908), 109-130.

See also the excellent work by TormaFranziska, Turkestan Expeditionen. Zur Kulturgeschichte deutscher Forschungsreisen nach Mittelasien (1890-1930) (1800/2000 Kulturgeschichten der Moderne 5), Bielefeld, here 21 u. 47. WolkersdorferGünter, Geopolitische Leitbilder als Deutungsschablone für die Bestimmung des “Eigenen“ und „Fremden“. Torma Franziska, Paradoxe Räume? Zur semantischen Konstruktion des Pamir als geo- und kulturwissenschaftlicher Forschungsraum. In: Lentz & Ormeling (eds.), 181-191.

v. Ficker Cenci, Turkestan und sein Gebirge. In: 15. Jahresbericht des Akademischen Alpenklubs Innsbruck, Klubjahr 1907/1908, Innsbruck 1908, 1-14, hier 13.

Zieme Peter, Von der Turfanexpedition zur Turfanedition. In: Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst et al. (eds.), Turfan revisited. The first century of research into the Arts and Cultures of the Silk Road, Berlin, 13-18.

Rickmers Willi R., The Duab of Turkestan. A physiographic sketch and account of some travels, Cambridge 1913, 3.

Today the river is connected via a channel (originally named after XXIII Party’s Congress of CP of USSR) to Amudarja.

Machatschek, Landeskunde, 6. Machatschek referstoJunge Reinhard, Das Problem der Europäisierung orientalischer Wirtschaft, dargestellt an den Verhältnissen der Sozialwirtschaft in Russisch-Turkestan, Weimar 1915.

КириченкоА. Н., ВасилийФедоровичОшанин. Зоологипутешественник (1844—1917), Москва 1940 (with list of publications).

v. Klebelsberg Raimund, Die Pamir-Expedition des D.u.Oe.A.V. vom geologischen Standpunkt. In: Zeitschrift des D.u.Oe.A.V. 45 (1914), 52-60, here 54.

Rickmers Willi R., Vorläufiger Bericht über die Pamir-Expedition des D.u.Oe.A.V. 1913. In: Zeitschrift des D.u.Oe.A.V. 45 (1914), 1-51, Bemerkungen zur Kartenskizze Heinrich v. Ficker, 50-51.