The Trans-Afghan Pipelines: From Pipe-Plans To Pipe-Dreams

Imran Khan*

Introduction

This paper aims to evaluate the prospects of building a natural gas trade and transport pipeline infrastructure, transiting Afghanistan and integrating the energy producing, surplus Central Asian and the energy consuming, deficit South Asian economies. The project has been called TAP after Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan signed a pipeline pact in 2002, and alternatively TAPI after India was invited in 2006 to join the project. In this article, TAP denotes the proposed trans-Afghan pipelines (TAPs). Tracing back to the emergence of Turkmenistan in 1991 as an independent oil and gas producing/exporting republic in the post-Soviet new energy world order, in 1994 Argentina’s Bridas which has in recent years partnered with a Chinese corporation in East-Asia and joined forces with British Petroleum in Latin America, proposed a TAP gas project following a successful exploration venture in Turkmenistan the preceding years. Union Oil Companies of California (Unocal), a US oil company that has been dissolved and merged in Chevron which Bridas approached for partnership on the gas project, in 1995 came up with a rival TAP gas pipeline.

That pursuit of prospective partnership has culminated into a no-threads-barred polarizing competition — and into a simultaneous cooperation. At a time when the Afghan war continued unabated, being abetted by ethnic, religious warlords and regional power politics, the TAP projects’ stakeholders, such as states and their administrations, their companies and their intelligence agencies, have all pursued partisan interests and agendas. Whether it was Saudi energy concerns DeltaOil and Ningarch or Pakistani governments of the centre-right Nawaz Sharif of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML) and the center-left Benazir Bhutto of the Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP), they were divided in their support of Unocal and Bridas and the consortia they constituted. The US, which had by then evolved a Caspian policy of multiple non-Russian, non-Iranian pipelines, threw its geopolitical weight behind Unocal which was courting the Taliban regime, while other regional powers such as Iran, Uzbekistan, Russia and India backed the anti-Taliban northern front of Uzbek and Tajik warlords. This geostrategic posing and equiposing has evolved a stasis, a stalemate, over the project. As a consequence, the pipeline projects have been on the anvil of Afghanistan conflict for more than one and a half decade, to no avail.

On the crossroads of the ongoing Afghan war, the TAP gas project has a circular history, of prospects on-again and off-again. As the Afghan warlords, either by internal forces or as external proxies, have changed hands over power in Kabul, prospects of the project have been phasing from extended periods of lows and into highs. Consider, for instance, the rise of the Taliban in September 1996 with the fall of Kabul and the fall of Taliban regime from the helms of power in the aftermath of the US declaring the ‘war on terrorism’, both gave a fillip to the prospects of the TAP projects. This paper, however, contends the TAP project as ‘pipe-dreams’. This assessment is based on the geopolitical predicament of the states and the South-Central Asian regions (greater Central Asia) the pipeline route involves. Along the route, Afghanistan is in a state of a seemingly ‘forever’ war, Baluchistan in southwestern Pakistan is mired in a state debilitating separatist insurgency, and Pakistan and India are locked in a relationship of perpetual animosity. Divided by disputed borders, these states constitute a disputatious neighborhood. Equally crucial is the pragmatic (involving a simultaneous competition and cooperation) geopolitics of energy security, for profits, power and primacy, over the transportation of geographically landlocked and geostrategically stranded Central Asian energy Dorado that muddles prospects of the TAP project by offering better and commercially viable alternatives.

Comprising four parts, the first section of the paper outlines briefly the history of TAPs, reflecting on the geopolitical developments and dynamics that have altered the prospects (from promising to being plummeting) of the TAP projects. Part two enunciates a framework for evaluating the feasibility of a pipeline project. Assessment of the prospects of building a trans-Afghan pipeline in the backdrop of a partisan and polarized geopolitical game of energy security follows. After analyzing the geopolitical, economic factors that have reduced TAPs as ‘pipe-dreams’ and rendered the TAP projects as ‘dry-holes’, the paper concludes that how a prospects enabling environment could be forged that could end the stasis.

The Trans-Afghan Pipelines (TAPs):A Geopolitical History

Proposed to integrate Central Asia’s energy-producing economies with the South Asia’s energy-consuming economies along a north-south geographic axis, the trans-Afghan oil and gas transit and trade route has also been described as a ‘North-South Energy Corridor’ (including a route transiting Iran). This has been reminisced as the resurrection of the ancient overland Eurasian trade routes, collectively described as the Silk Route, when Khyber and Tochi passes on the present Pak-Afghan borders served as the key transit and transportation points in and out of South Asia from and to Europe across the Central Asian transit area. In other words, the TAP was a plan meant to transport and trade gas and oil from the Russia’s near ‘southern abroad’ (including Central Asia and the greater Caspian Sea basin) across the energy ‘land-bridge’ Afghanistan to far ‘southern abroad’ (South-West Asia and the greater Indian Ocean region), providing an opening to the CARs’ landlocked energy resources onto open sea trading routes and into regional markets.

The idea of building a ‘north-south’ energy corridor came in the wake of the epoch-making disintegration of the Soviet Union in December 1991, a ‘fat-tail’ development that has altered the political map of the region just as the geopolitical milieu of the world. Consequently, the Central Asia Republics (CARs), in the eastern Caspian Sea basin, has moved centre stage on the world’s energy geography as a new energy frontier. Subsequently, a new energy “rush” has also followed. (The first “rush” had occurred in the western Caspian Sea basin in the Baku region of the post-Soviet Azerbaijan. That began in 1870s when Russia leased oilfields to the Noble Brothers for development, who would later design the world’s first oil tanker Zoroaster and develop a network of crude oil pipelines, and culminated in 1900 when the Baku oilfields produced more than a half of oil the world produced then). Ever since, the geopolitics of energy security has evolved in Central Asia just as in the greater Caspian Sea region, pivoting on energy trade and transport via oil and gas pipelines transiting peripheral Eurasian regions into energy markets in Asia and Europe. Of the ensuing pipeline tangle, Iran has constructed a pipeline under a gas-swapping deal with Turkmenistan — and also imported oil by ships through the Caspian Sea from Kazakhstan. Russia has developed another pipeline to its Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, consolidating its stranglehold over the Kazakhstan energy in particular and Central Asia in general. The United States in collaboration with Turkey has built a non-Russian, non-Iranian oil pipeline from Baku to Ceyhan (the TBC pipeline) along the Mediterranean Sea shores, partially eroding Russia’s energy trade monopoly in Eurasia. China has routed two pipelines, building an oil pipeline from an onshore field in Kazakhstan and inaugurating a gas pipeline from Turkmenistan crisscrossing Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

Up staged by rival pipeline plans, the proposition of a trans-Afghan gas pipeline, and the geopolitics it has ushered in, has manifested a historical reversal of fortunes and an epochal change of roles for Central Asian and South Asian energy economies. The Central Asian “heartland” (as Sir Halford J. Mackinder in The Geographic Pivot of History described it) has evolved from being a transit and trade land-bridge of a greater Eurasia to being a landlocked energy-exporting province. Spatially and economically, the South Asian “rimland” (as an eminent US Naval historian, Alfred Mahan, put it), at the confluence of the World “Ocean” and the “World Island” (the Eurasian landmass), has become partly an energy importing and exporting as a transit arena (Pakistan and Afghanistan in some ways retained their historic roles as trade, transit geographies).

The TAP gas pipeline could be tracked back to 1994. As the Cold War ended, Bridas, an Argentinean energy corporation, founded in 1948 as a family business in Latin America, ventured in Eurasia (Russia’ Siberia) in 1987 and Turkmenistan after the Soviet Union socialist, straightjacket and centralized, economy was dissolved in 1991. As being the first international post-Cold War investment, Ashgabat partnered Bridas. In a joint venture, Bridas leased Yashlar gas and Keimir oil fields in eastern and southern Turkmenistan (sharing 50:50 and 75:25% respectively). Gas was successfully explored at Yashlar and exported north to Russia via a Gazprom run pipeline network. However, Bridas wanted to trade its gas south to “alternative markets”, as Bridas’ Chairman Carlos Bulgheroni called it, of Pakistan and India in South Asia and of China in South-East Asia. Finally, it chose the trans-Afghan southern route instead of the trans-Central Asian eastern route.

In 1994, Bridas’ CEO Bulgheroni proposed a TAP gas pipeline project to Ashgabat. Fascinated and enthused, President Saparmurat Niyazov (also know as Turkmenbashi, father of all Turkmens) readily endorsed the project. As a “special emissary” of Turkmenbashi, Bulgheroni liaised with Pakistan, as a prospective market for Turkmen gas under the proposed TAP project. Then, Bridas mapped a 1,400 kilometers route, between Yashlar in eastern Turkmenistan and Multan in southern Pakistan. That included Herat in southeastern and Kandahar in southern Afghanistan and Baluchistan in southwestern Pakistan. It also proposed to extend a section of the pipeline across the great wall of distrust to northwestern Indian, Faizabad, and even still other sections to Iran and other CARs. It planned an “open-access”, open-end gas export-import pipeline, providing other regional producers and consumers access to its energy trade, transit and transport infrastructure. The objective was to increase probability of building the pipeline, improve long-to-medium term commercial viability of the project and neutralize or up-set competition to it from other gas export and import rival projects. The following year, a team of technical experts led by Bridas’ Transportation Manager, Louis Sureda, toured Afghanistan and surveyed the route. Cost of the project was estimated 2.5 billion US dollars.

In February 1996, Bulgheroni while boasting the pipeline as a peace-making project secured a “right of way” for 30 years from Burhanuddin Rabbani, the then ‘interim’ Afghan President, after an extensive and challenging diplomatic maneuver on the Afghan landscape. In November that year, Gen. Rashid Dostum, an Afghan warlord who had consolidated in Herat bordering Iran his fiefdom, acquiesced to the project too. That month, the Taliban also reached a pipeline accord with Bridas. Prior to being deposed by the Pakistan Muslim League later in the year, the PPP government in Islamabad reached an agreement with Bridas on importing 20 billion cubic meters (bcm) gas on a take-and-pay term. Wanting the pipeline to become operational by 2001, the company planned a 30 months construction period. Given the Taliban’s opposition to foreign direct investment by western companies and international financial institutions, Bridas constituted two consortia. For building a pipeline inside Afghanistan, Bridas hammered out a 50:50 “trans-Afghan-Pakistan pipeline partnership” with a Saudi Arabian company, Ningarch, which was backed by Saudi intelligence agency. To constitute the second consortium, Bridas’ executives approached Russia’s Gazprom, United States’ ExxonMobil, Amoco and Unocal and Pakistan’s Crescent Group. This would become a critical watershed, game-changer, page-turner development in the evolution of the geopolitics of TAPs, holding in stock an upset for Bridas.

Thereafter, the trans-Afghan pipelines have evolved in four phases. Corresponding to the ebb and flow of the Afghan war, four different-without-a-distinction TAP projects were proposed: The pre-9/11 2001 Unocal’s CentGas Pipeline and Central Asian Oil Pipeline (CAOP) and the post-9/11 Asian Development Bank (ADB) supported TAP gas and oil pipelines. However, the TAP oil projects remain peripheral to gas pipelines and were hardly pursued beyond the initial propositions. This, in part, was due to the geographical proximity and geological substantiality of Turkmenistan’s natural gas reserves, and rhetorically to the country’s limited oil reserves (estimated the country’s oil reserves 0.5 billion barrels and as of 2006 produced 163,000 barrels) and the other CARs’ commercially committed reserves.

In 1995 Unocal, a defunct Houston-based US oil concern that was founded in 1890s and floundered in 2005 after being merged in Chevron as a result of a Sino-American corporate battle that began with a CNOOC Ltd 18.5 US dollar ‘big bid’, proposed a variant of Bridas’ gas pipeline. That was named after the Central Asian Gas (CentGas) Pipeline consortium Unocal constituted in 1997. The CentGas pipeline was 2,090 kilometers, stretching from a Soviet-era Daulatabad gas-field in southeastern Turkmenistan across south-eastern Afghanistan and southwestern Pakistan to northwestern India to New Delhi. Unocal also proposed a parallel trans-Central Asian oil pipeline across Afghanistan, i.e. the Central Asian Oil Pipeline Project (CAOPP). The latter one was designed to link Russia’s Omsk oilfield in Siberia across Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, connecting Turkmenistan’s Chardzhou oilfield en route to Pakistan’s coastal city of Karachi, in Sindh, via Baluchistan.

That year in September, Unocal concluded a 30-year “gas pricing” pact with Pakistan amid a surging hope of the Taliban restoring peace to the war-ravaged Afghanistan. They were expected to bring the state back from the brinks of balkanization, establish a centralized but ethnically pluralist popular government in Kabul with a writ reaching far and wide in east and west, north and south, centre and periphery. A year later, after overtaking warlords in eastern Afghanistan in a military victory one after another, they seized power in Kabul in September 1996. As their onward march continued into northern Afghanistan, in May 1997 Pakistan (the PML government of Nawaz Sharif), Afghanistan and Turkmenistan on the sidelines of an Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) summit in Ashgabat signed a ‘framework agreement’. They agreed on a feasibility study on the pipeline by Unocal. In October, a “tripartite commission” was instituted. Thereafter, Unocal (holding a 46.5% share) partnered Saudi Arabia’s DeltaOil Company (15%) to constitute later on the CentGas consortium, with Russia’s Gazprom (10%), Turkmenistan’s Turkmengaz (7%), Japan’s Iotochou (6.5%), Indonesia’s Petroleum Inpex (6.5%) and Pakistan’s Crescent Group (3.5%).

While putting pieces of the project’s jigsaw together cautiously and successfully being supported the US government which in 1995 has evolved a geostrategic posture on the Caspian Sea and littoral region after years of geopolitical pondering (containing Russia, Iran and China were its main policy planks), Unocal suffered a setback on geopolitical front. In August 1998, the US Central Command in the Indian Ocean fired cruise-missiles at suspected al Qaeda hideouts and training-camps in southern Afghanistan along the Pakistani border. Consequently, Unocal was left with no option than to put its project on an “indefinite hold”. Subsequently, it closed its offices in Pakistan (closing its operation, it established since 1970s) and Afghanistan (including two vocational training centers in Kandahar and Mazar e-Sharif). In December, it abandoned the CentGas consortium, as did Gazprom earlier, squandering 20 million US dollars on the rogue Taliban regime. Marty Miller, a senior Unocal official, dubbed the pipeline as a “dry hole” (that refers to a failed oil exploration well). Miller also commented the project would not be revisited unless Afghanistan was pacified and a stable popular government was in place in Kabul. Pressure at home front surged too, with US senators and human rights activists, among others the then First Lady and now US Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton, criticized Unocal for its overlooking the Taliban human/women rights abuses. President Bill Clinton’s administration also was pressured.

While it continued to rival Unocal in a US court of law, challenged Ashgabat’s contract obsolescing tactics in an international commercial court of arbitration, and on the geopolitical ‘chessboard’ of central Eurasia, Bridas received a buck off the Unocal’s bust. With Unocal out in the wilderness, the company made a comeback by securing a pipeline deal from the Taliban in August 1998. The Taliban’s acquiescence could have been a reaction to the US missile strikes. With that, Bridas moved centre stage, outflanking Unocal. The Bridas-Unocal duel for the gas pipeline (and for profit, power and primacy) dates back to April 1995 when Bridas’ Bulgheroni introduced Unocal CEO Roger Beach to President Niyazov in New York as a prospective partner. Soon after, a Unocal delegation visited Ashgabat and persuaded Niyazov. In October 1995 President Niyazov, buoyed by the attention of a US company and a possible US backing in its wake, singed a pipeline deal with Unocal in New York. However, when Unocal abandoned the CentGas project, in April 1999 Niyazov renewed the suspended deal with Bridas. In July the US and United Nations imposed sanctions on the Taliban regime and the TAP project thawed, to be revisited by President George W. Bush and his energy league led by Vice President Dick Cheney. The Bush administration replenished US pipeline diplomacy, which Deputy Secretary Strobe Talbot forged for the greater Caspian Sea region in October 1995. Taliban delegations, one after another, were courted and hosted in Washington, Berlin and Riyadh. Washington funnelled 125 million dollars to the Taliban regime as “drug war funds” and humanitarian assistance. These financial bounties accompanied US bullying and brinkmanship. Offering a “carpet of gold”, Washington reportedly had ordered the Taliban to surrender Osama bin-Laden, close terrorist camps and grant transit rights to US energy companies. As the Taliban refused to make concessions, the US threatened them with a “carpet of bombs”, to no avail too.

Then came in 2001 the 9/11 terror strikes on the US soil. In reaction, the White House declared a ‘war on terrorism’ on ‘the axis of evil’ of Islamist terrorists and Jihadi networks worldwide. A month later, the Taliban regime was bombed, followed in 2003 by bombing of Iraq, which analysts have described as ‘resource’, ‘oil’ and ‘pipeline’ wars’. As the Taliban militia and al Qaeda militants welted under US bombing out into southern Afghanistan and across the Durand Line into Pakistan’s tribal areas, the TAP pipeline project received a fillip. Wendy Chamberlain, the then US Ambassador in Islamabad, called on Pakistan’s Minister for Petroleum and Natural Resources, Usman Aminuddin, on 9 October 2001, to discuss likelihood of the TAP project. After a surrogate, satellite administration was installed in Kabul, Pakistan’s Chief of the Army Staff-cum-Chief Executive, General Pervez Musharraf, and Afghanistan’s ‘Interim’ President, Hamid Karzai, agreed in-principle in February 2002 to pursue the project in their countries’ common interests. The following month, President Karzai in a meeting with his Turkmen counterparty Niyazov in Ashgabat discussed the possibility of revisiting the gas pipeline. In May, they singed a “framework” agreement on the gas pipeline project. In the accord, they also intended to constrict an oil pipeline. A “steering committee” was instituted to actuate the project.

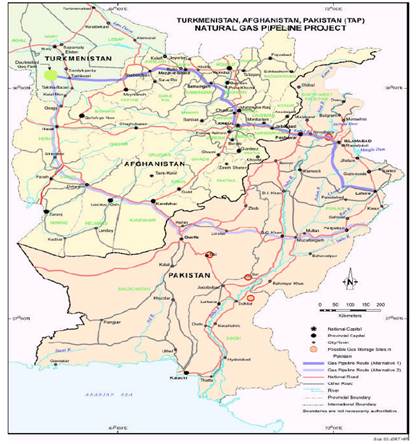

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) was engaged as a “development partner”, which undertook several feasibility studies on the pipeline. While espousing the “southern route” (the Herat-Kandahar, Quetta-Multan and New Delhi axis), ADB also proposed an alternative “northern” route, across Mazar e-Sharif, Kabul and Jalalabad (Afghanistan), Peshawar, Rawalpindi and Lahore (Pakistan), and in later stages be extended to Ahmadabad (India). (See a map of the TAP gas pipeline by ADB). Eight year after since Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan has singed the “framework” agreement, prospects of the TAP gas project are being dwarfed by the ongoing Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan and the continuing Baluch insurgency in Pakistan. On a trajectory of dwindling prospects of realization, the pipeline is dubbed varyingly but for almost identical reasons as a “no brainer”, “moon-shot”, pipe-dream, pipeline to nowhere and a political pipeline.

Analyzing Prospects of Energy Pipelines: A Primer

Pipelining energy resources is a complex, long-gestation and graduated process. A number of factors — constants and variables — manifest to various degrees prospects of energy pipelines. Ranging from geopolitics to geoeconomics, geographic contiguity to geological endowment, these influences dovetail into a feasibility evaluation pyramid. Of these, geopolitical predicament (including, among others, security situation, political circumstances, relations between states, border regime) of a given region constitutes the base of the pyramid and energy economics (comprising supply and demand for oil or gas) makes the tip. Constructing a pipeline infrastructure (a network of pipes, compressors and power generators) requires a huge up-front investment in billions. Pre-construction, a complementarity of oil or gas demand and supply is established, compatibility of geopolitical interests of prospective trading partners is contrived, conduciveness of security environment is conceived, and a dispute settlement mechanism is composed. All of them have critical bearings on immediate prospects of routing a pipeline network and long-term viability of such a capital intensive venture. A pipeline once built cannot be modified, its throughput (capacity) ramped up or reduced — a pipeline that operates below a ‘throughput’ capacity pipeline runs into commercial losses. As painstaking is the process of building a new pipeline, assessing the prospects of a proposed pipeline is as stock-taking exercise. Before committing to analyzing prospects of the TAP project, outlining an overarching analytical framework for evaluating the prospects of energy trade, transport and transit pipelines is necessary. That is deciphered in this section.

Rationalizing energy demand and supply complementarity is a necessary first step in evaluating the prospects of a proposed pipeline. End to end, the presence of energy (oil and gas) gushing economy at one end (in other words, threshold) and energy guzzling economy at the other end (read, wellhead) in a reasonable geographic proximity (in range of 3,000 kilometers) is a precondition, a project starter. Therefore, given the fact that a pipeline is a dedicated supply chain, an energy supplier’s (suppliers’) capacity for production and willingness to prefer a single, dedicated market over an open, diversified market for exporting oil and gas resources, and a consumer’s (consumers’) demand (net importer) for and agreement to import in the long run, is determined. That is formalized through sales and purchase agreements (SPAs). Beforehand, volumes of gas/oil are defined and pricing formula agreed upon (including a mechanism for price revisions). Once that complementarity of demand and supply is found, the process phases into technical and engineering aspects of a pipeline development project.

Following that, a blueprint of pipeline infrastructure is designed on the basis of terrain and temperature, demand and supply, distance between wellhead and market. A paper pipeline is built, outlining parameters and fundamentals of a pipeline network. A preferred, and in some cases compared with alternative, transit route is identified, length and breadth of a pipeline measured, throughput (volume) capacity defined. These are critical building blocks for building a gas pipeline. Transiting and transporting gas, either through pipelines or liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals, is more laborious logistically, far more tedious technically and more complicated topographically than oil. Natural gas flow is affected by changes in weather, variations in length and modifications in pipeline structure. A gas pipeline is worked out within certain limitations, requiring “grid balancing”, heating up (in winter), maintaining a steady stream. Natural gas has “reconnecting problems” and restoring a disrupted flow is costly. Owing to these technical factors, a gas pipeline through an unstable region is avoided. Utilizing a pipeline’s full capacity is important too, for a pipeline operating below capacity is lesser cost effective and competitive.

This pipeline blueprint is substantiated by commercial (gas or oil trade) agreements and political (legally binding sovereign) guarantees. Creating a right “balance of interests” in a project and agreeing on a clearly defined rules and procedures for implementing and operating a pipeline is a next logical step. Likewise, necessary are signing sovereign state agreements on trading, transiting and transporting oil and gas, reaching SPAs between a project development and pipeline construction consortium and states, defining upper and lower limits for rents, royalties and prices (reaching a plateau between expensive and cheap gas/oil). Dispute settlement mechanisms and price adjustment formulas are finalized, foreshadowing potential grey areas of disputes. A unanimous, overarching legal regime is instituted, whereby hammering discrepancies out in legal frameworks of states and to protect the venture against obsolescing bargaining measures by stakeholders. To shore up necessary capital and investment (in billions), a consortium or consortia of national and private companies is constituted, whereby splitting losses and profits.

Pipelining energy has geographical and geopolitical determinism. As logistical determinism can be identified the lack of and the necessity to develop a transmission infrastructure and geological determinism can be defined by the existence and nonexistence of limited and abundant oil/gas reserves, a pipeline’s geographical determinism is manifested by either spatial location of energy resources, access to sea or being landlocked and distant from markets or proximate to consumers. In this light, the Central Asian oil-gas Dorado is landlocked, distant from seashores, but is contiguous to lucrative, both matured and maturing, energy markets in Eurasia. Topping pipeline viability determinants is geopolitics, being defined as the pursuit of natural resources and possession of strategic geographic areas/locations either by means of military power or economic prowess, coupled with geoeconomics. Reflective of political, economic, security and strategic priorities of the states and corporations (multinational or national) involved in the geopolitics of energy security, they can equally buck or bust a pipeline project — as well other building blocks. In other words, they can render a project as a pipe-dream or a reality. Moreover, hence, a pipeline project is wrought in a geopolitical predicament and is fraught with geopolitical risks. Manifesting imperial hubris and engendering monopoly control, the prospects of a pipeline are determined by inter-states relations, intra-states political and strategic circumstances, intra-regional security conditions, strategic and security posturing. At the same time, an energy pipeline can be an economic lifeline and could be a geopolitical faultline having a potential to funnel energy resources from oil and gas fields to markets and fuel resources wars. Similarly, they can create mutually beneficial co-dependencies and cause mutually harmful conflicts.

Pipelines integrate, horizontally as well as vertically, energy economies across a swathe of sovereign (purely transit, partly trading) territory and involve a pooling of energy and economic resources. Beyond this configuration of co-dependent trade relationship, pipelines as mentioned above also create natural monopolies. Building this end-to-end, devoted energy trade, transit and transport infrastructure is essentially the pursuit of energy security. That is an uninterrupted, cost-effective, sufficient and environmentally friendly supply of oil and gas, among other resources like coal, uranium and water. This can be accomplished by means of building security blocs, coalescing geostrategic partnerships, developing military bases and deploying forces across energy bearing and transit regions, creating economic linkages, making investment in up-and-down-stream projects. A pipeline assimilates all these elements of energy security, providing a steady, predicable, dependable, long lasting, cost effective and environmentally efficient energy supplies. Beside supply and price predictability, the ultimate prize, however, is profit, power and ultimately primacy in a globalized geopolitics.

By these measures, if energy is the lifeblood of modern hydrocarbon-propelled industrialized-economies, energy pipelines are the lifelines of primates in power politics. For building and operating pipelines, peace and security along the routes is crucial. Hence pipelines are built in peace, not in wars, and if built without peace states may wage wars to protect them against religiously motivated terrorism and political motivated ethnic violence. Equally critical, in the same vein, is the nature of relations, both to peace and pipeline, between states prospecting partnership in a pipeline project, given the fact that pipelines can be built in a geopolitical concord, not discord. Thus, routing pipelines is a manifestation of the commonalties of interests and the complementarities of strategies. Geopolitical discords among would-be protagonists and partners and political instability along a pipeline route are feasibility faultlines.

The Tap ‘Greater Central Asian’ Energy Projects: Pipelines for Peace, Mired in ‘Resource’ Wars

Case in point is the trans-Afghan Turkmenistan-Pakistan (and India) gas pipeline project. The geological, geographical (distance, not disputes), geoeconomic and energy-economic feasibility determinants are conducive and complementary. Debilitating, however, is geopolitics, as the project proposes to bridge energy producers and consumers of Central Asia and South Asia across a war zone (Afghanistan and Baluchistan) that rivals not only proposed but also the commercial viability of existing (such as Russian and Iranian) pipeline networks. This section after describing briefly the geo-energy, economic complementarities highlights the geopolitical incompatibilities and geographical incongruities that have dwarfed the prospects of the pipeline, being described as a pipe-dream.

The TAP project’s energy wellhead and threshold economies are correspondingly paired and are complementary. The supply deficit of Pakistan and India is in league with Turkmenistan’s supply surplus. Turkmenistan is a gas gusher, boasting a stranded 71,000 billion cubic feet (bcf) commercially exploitable reserve of proven gas. Pakistan, on the other hand, is a gas guzzler, projecting a staggering 164 million tones of oil equivalent (mtoe) gas demand by 2030 — accounting for 45 percent of its primary energy supply mix of 361 mtoe. As the former is a net (the world’s sixth leading) gas exporter trading 639 bcf of the total 2,234 bcf it produced in 2006, the latter is Asia’s leading gas intensive energy economy, prospecting an estimated 141 Mtoe supply lag by 2030 (expanding from a projected 22 mtoe in 2015) in the past 27 years. Between 1980 and 2007, its gas consumption has increased from a just 300 bcf to 1,088 bcf. By including India, the energy-economic complementarity of the TAP project curves up, increasing prospects of the project.

Logistically the route is feasible too: Routing across south-eastern Afghanistan to southwestern Pakistani province Baluchistan, the pipeline has been proposed to integrate with the country’s extensive gas distribution network (totaling 56,400 kilometers) or reach Gwadar port for onward exports to Asian and world markets. ADB has conducted a number of technical, logistical surveys on the pipeline and has worked out a basic project design, considering the pipeline economically, commercially and logistically feasible. Moreover, the TAP pipeline has been supported by other international financial institutions, such as the World Bank (WB). Even still, the pipeline falls within the US’ greater Central Asian geostrategic project (integrating Central Asia and South Asia via energy transmission networks) and Caspian Sea policy posture (building multiple pipelines, containing Iran and Russia), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s (SCO), Economic Cooperation Organization’s (ECO) and Association of South Asian Countries’ (SAARC) regional energy security and trade cooperation frameworks, and within the working dynamics of the Friends of Democratic Pakistan (FODP) caucus and the international coalition (including US/NATO, named as International Security Assistance Force, ISAF) for a secured, peaceful and prosperous Afghanistan and stable Pakistan (or the AfPak region).

Notwithstanding a plethora of pipeline feasibility positives, the TAP project stands tall among pipeline plans that have crowded Central Asia in 1990s as a ‘pipe-dream’, a ‘dry-hole’. This is due, in particular, to the geopolitical realities of Central-South Asia and the political circumstances of would-be-partners countries, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. For the following reasons, the project has been cynically described as a shot-in-the-moon, pipeline-to-nowhere and political pipeline, with its prospects being premised on a paradigm shift in the geopolitics towards the restoration of peace, the reformulation of inter-states relations and the restructuring of security paradigm.

- Afghanistan: A Feasibility Quagmire: Afghanistan is the TAP project quagmire. The apparently lasting Afghan war, festering for nearly 30-odd years, has made the country a “spectacularly unsuitable as a transit country”. With the government under siege in Kabul by a mounting Taliban insurgency and a larger than state Afghan warlords. By sustaining anarchy, they have been cashing on poppy cultivation and narcotics trade and have been reigning supremely on the periphery. A fragile Afghanistan, which former US ambassador to Afghanistan and then Iraq dubbed as an energy “land bridge”, is a pipeline ditch, curtailing its prospects as a doable economic venture.

Constructing a pipeline through south-eastern Afghanistan, where (in Helmand province) the British forces could not reconstruct a power generation plant, is a nightmare because it involves restraining human toll and refraining capital cost at the hands of the Taliban. Anyhow, even if a pipeline is built, too frequent disruptions could make maintenance of the pipeline for an operating company costly. Protecting the energy transmission infrastructure also will cause the Afghanistan National Army, the Afghan National Police or the NATO/ISAF/US forces a strategic exhaustion, as Baluch separatists are causing Pakistan.

- Baluchistan: A Viability Quicksand: The problem of protecting a pipeline and keeping the project running undisrupted continues across the Durand Line, as the war zone expands eastward into Pakistan’s southwestern Baluchistan province. The Taliban after being dislodged from Kabul are suspected to have headquartered in Quetta and constituted the so-called “Quetta Shura”, a nerve center of the ongoing Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. They have been bombing oil trucks en route to Afghanistan and attacking NATO/ISAF forces in that country by crossing the fractious, fluid border over (having more than 250 crossing points and comparatively few security posts). The US reportedly has threatened drone missile and overland surgical strikes against the Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan.

Baluchistan is an ethnic cauldron too. Spatially the largest, Baluchistan is sparsely populated (comprising more than 40 percent of the area and nearly 4 percent of the total population), gas-producing (second after Sindh) and economically poor province. Baluch nationalists who feel deprived, impoverished and marginalized at the hands of Pakistan’s civilian, military and Punjabi elites have continually waged a ‘resource war’ on the country. They destroy energy installations and gas transmission infrastructure and kill government officials, security forces and Punjabi settlers (whom they consider occupiers) in sporadic targeted attacks. They have sustained a civil war in the province since 1950s. Different factions (tribal groups) demand varyingly greater ownership of natural resources, greater governing and political autonomy and even a greater, independent Baluchistan (comprising Baluch population and provinces in Afghanistan and Iran, overlapping the greater Pakhtunistan) state.

As a consequence of these phantasmagoric insurgencies continuing unabated, Pakistan constitutes the eastern fringe of the pipeline quagmire. Similar to Afghanistan, Baluchistan being the transit route, in particular, is the pipeline viability quicksand and Pakistan being a trading partner, in general, is the feasibility wildcard. With the Pakhtun Taliban holed up in the tribal areas, the Punjabi Taliban, based in Punjab, launch terror strikes inside the mainland Pakistan and across the border in India.

- India-Pakistan: Prospective-Partners, Perennial-Enemies: In spite of being slated as potential energy trade partners, Pakistan and India make a hostile neighborhood, as do Pakistan and Afghanistan. Boasting one of the largest standing armies and bullying each other with a nuclear arsenal, they have been in a state of cold war. They talk peace (composite dialogue process) and wage wars (three full-scale wars). Among a slew of territorial and water conflicts, they dispute Jammu and Kashmir. Each state, following the 1948 Kashmir war, is occupying a half of the territory, divided by the Line of Control (LoC) the two states agreed in early 1970s, while posting ownership claims to the other half as being intrinsic to their ‘geo-bodies’. Divided by a great wall of mistrust and hostility, each state considers the other as an existential threat. New Delhi has been accusing Pakistan of waging a covert, clandestine war against it in the Indian-held Jammu and Kashmir (IHJK) and launching terror strikes against civilian targets in its cities and citizens. Islamabad, on the other hand, has been suspecting India of working against Pakistan from Afghanistan, abetting the Baluch insurgency.

In such an environment of open-hostility building a pipeline for peace is a project in utopia, a naïveté. India cannot rely on Pakistan for the supply of a strategic raw material such as oil and gas or energy security, which has during the twentieth century evolved as the foremost (second only to territorial integrity) national security concern, pivoting on a pipeline that transit an arch-enemy’s territory. For Indians, though dependency on Pakistan, or even co-dependency relationship with it, that could ultimately engender a monopoly control allowing Islamabad a stranglehold over its economy, is a geopolitical misnomer and a geostrategic capitulation.

Although India has never been forthcoming, while engaging New Delhi in pipeline diplomacy, Pakistan nonetheless has been bulwarking India’s reach to its ‘extended’ neighborhood in Western and Central Asia, barring rather than bridging its way to the energy rich regions. Strategically, they have been engaging each other, whereby pursuing their policies of benign but malignant containment. So doing, Islamabad has been subjecting the TAP gas project to India-resolving-the-Kashmir-dispute-first (which implies India acceding IHJK to Pakistan) and India has maintained a Pakistan-back-rolling-the-terrorist-infrastructure-first policy. India, which accords the pipeline economies of scale, for geostrategic reasons has been pursing a ‘one-step forward, two-step backward’ approach towards the project, thereby remaining non-committal.

- Afghanistan-Pakistan: Swapping Imperialistic Designs: Disputed borders that delineate the trans-Afghan arc of the Islamic insurgency, the cauldron of ethnic instability and the crucible of interstate hostility drain the TAP project of any remaining prospects. Afghanistan and Pakistan, just like India and Pakistan, are disputatious neighbors, contesting the legality and political relevance of the existing frontier, the Durand Line. Being a colonial legacy that Pakistan inherited as an international frontier after the partition of India in 1947, the border was marked in the early 1890s by the British India government and the ‘Iron Emir’ Abdur Rehman of Afghanistan.

Against this backdrop, Kabul until the 1979 communist Saur Revolution pursued the policy of a ‘greater Pukhtunistan’. Kabul has been claiming, in part by New Delhi’s prodding, Pakhtun dominated regions of Pakistan as parts of the Afghan territory. Pakistan has been counterpoising Afghanistan’s policy indiscretion by pursing a ‘Strategic Depth’ policy. That strategy has been improvised to avoid a two fronts war and install a friendly government in Kabul. Even a weaker, fractured Afghanistan was preferred over a stable, strong and an Indian friendly one. This defensive-offensive geostrategic posture underpinned by Pakistan’s threat perception has been interpreted by analysts as the Pakistan Army’s effort to make Afghanistan Pakistan’s fifth province. As a consequence of this abysmally failed strategy, Pakistan confronts an unstable and a suspicious Afghanistan on one hand and a Taliban, Islamist insurgency and a militant backlash on the other.

- Making ‘Pipelinistan’, Shoring-Up Geopolitical Buck: In addition to the foregoing feasibility negatives, the TAP gas project has no geopolitical buck, a pipeline feasibility determinant that could trump other feasibility detriments. Unless an overarching, overshadowing geopolitical buck is improvised, a pipeline is unlikely to be actuated by means only of political declarations, policy postures or constituting steering committees, and even by reasons of economic and commercial viability and profitability. With this buck, in which national energy companies serve as corporate conduits, a pipeline could be routed through a region without the precondition of peace being met. Cases in point of the pipelines built without peace in transit regions: Whether it was the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC), Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) and Sino-Kazakh oil pipelines, or the Sino-Turkmenistan (trans-Central Asia) gas pipelines, all have cut geo-political-economic busts dynamics through and crowded rival projects out, including the TAP gas-oil projects.

Contrary to those, the TAP project has invoked a polarized, not a concerted and coherent, effort. Whether it was the Bridas-Unocal competition, Saudi energy concerns DeltaOil partnering Unocal and Angarsk allying Bridas (as did Saudi intelligence), a divided Pakistani ruling elite with the PPP government (resisting, in part, US bullying) supporting Bridas and that of the PMLN backing Unocal, all manifest a piecemeal and polarized effort. However, whatever cooperation the 2002 framework pipeline agreement could muster was hijacked by would-be-partners for promoting their partisan, and at times rival, agendas. The trilateral ministerial Steering Committee convened since its first meeting in 2002 more than eight times was reduced to a talking shop, failing to shore necessary geopolitical support up for the project. Similarly, as much fractured has been cooperation over the project as fierce the competition. Russia, China, Iran, Turkey have all pragmatically pursued their energy trade, transport and transit plans, diverting Turkmen and Central Asian oil and gas reserves the TAP projects proposed to market in South Asia.

Having a stringent competition, too much of insecurity along the route and too little a geopolitical backing, the TAP project has remained for too long a period (about 15 years) on the anvil, to no avail. Among the numerous rival projects the TAP gas project faces, the Iran-Pakistan (IP), or the expanded Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI), gas pipeline is more potent. Although the pipeline confronts US opposition under the Iran-Libya Act sanctions, the route instead of crossing the shattered state Afghanistan enters Pakistan after traveling a 1,000 kilometer distance in Iran. Equiposing the US’ containment policy, Russia supports the project that could reduce the chances of diversion of Turkmenistan’s gas from its pipeline monopoly and give Moscow stakes in the South Asian energy markets. Tehran has already constructed a major section of the IP-line within its borders and has reached agreements with Pakistan on the project (recently in 2009 and 2010). However, with its economy in a perpetual depression, its debt servicing liabilities and constrained by the war on terrorism, Pakistan’s inability, in the long run, to pay for the gas, let alone funding construction of the TAP pipeline, without Indian partaking in the project, increases the plausibility of the ‘pipe-dream’ prognosis.

Ending the Stalmate, Overcoming the Stasis: Is there a Way Out?

Together with geoeconomic, geographical and geological factors, the contours of a trans-border, multinational, multibillion investment, oil and gas (trade, transit and transport) pipeline infrastructure are set in and determined by geopolitical predicament (circumstances and security conditions) of a given region in general and the geopolitics of energy security in particular. Combined, these can equally bust and buck the prospects of a pipeline project. Thus, shoring an overarching geopolitical buck up for a project is a necessary strategy to trump and overshadow refraining geopolitical circumstances and restraining security conditions to pipelining energy resources.

Given the geopolitical predicament of the grater Central Asia, the TAP gas project for the foreseeable future — apparently as long as Afghanistan continues to be a war zone — remains a ‘pipe-dream’. For, it is mired in a seemingly unending long war in Afghanistan, and is marooned by the polarized, partisan but pragmatic energy geopolitics. Unless peace returns to Afghanistan, India reconciles with Pakistan as an energy transit and trade partner, and Pakistan grants greater autonomy to Baluchs and seeks a political solution, instead the military one, to the conflict, prospects of the project are unlikely to improve. Thus unless Afghanistan is pacified and writ of the state pivoting on Kabul restored, Pakistan is stabilized by appeasing the Baluch nationalists and putting out the Taliban insurgency out, India revisits Pakistan as an partner country by resolving amicably the existing territorial and water disputes, and Pakistan, Afghanistan and India reconfigure the disputed frontiers by recognizing them as de jure international borders and establishing trading links, the TAP project will continue to remain a “dry-hole”, a shot in the moon. Critical also is the three countries agreeing to stop using ethnic minorities and religious majorities in each other’s territories as “political pawns in complex power games” . Forging a new security regime in the greater Central Asia, along the route, can help the stakeholders engaged achieve a level playing field and ultimately actuate the much anticipated and prospected project.

Improvising a geopolitical buck also is needed, because the prospects of the TAP gas project are severed by geopolitics and will take geopolitics to serve it. Only an unprecedented good-will between the states involved will develop a basis and a rationale for an energy-economic interdependence. Re-crafting national security strategies, reconsidering national geostrategic pursuits, and re-defining regional security regime, in turn will determine the level of good will and define contours of cooperation. The stakeholders, therefore, should collectively take appropriate measures and marshal necessary means, ramping up prospects of building a pipeline across Afghanistan. That includes reconciling differences, resolving disputes, reframing legal, political and structural regimes, working out risk mitigation and management measures. This should be gradual, sequential and orderly not sweeping and drastic, each succeeding step complementing a preceding one. Ultimately, the prospects of the TAP project could be upped on a positive trajectory, and so could be the post-construction commercial viability of the project.

Bibliography

Ahmed Rashid, The Resurgence of Central Asia: Islam or Nationalism? (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1994).

Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia (1999).

Ahmed Rashid, Descent into Chaos: The U.S. and the Disaster in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia (The US: Penguin, 2008).

Alex Whiting, ‘Afghanistan Still the ‘Sick Man’ of Asia’, Reuters, London, 20 June 2005.

Angelo Rasanayagam, Afghanistan: A Modern History (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005).

Andrew Heywood, Politics (London: Macmillan, 1997).

Asia News Channel.

Asian Development Bank (ADB), Technical Assistance for the Feasibility Studies of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan Natural Gas Pipeline Project, TAR: STU 36488, December 2002.

Ahmed Rashid, ‘Pakistan Crisis ‘Hits Army Morale’, BBC News, 13 September 2007.

Ayaz Amir, ‘A Banana Republic without Bananas’, Dawn, Islamabad, 01 February 2002, p.7.

C. Christine Fair, ‘Pakistani Attitudes Towards Militancy in and Beyond Pakistan’, Saving Afghanistan, V. Krishnappa, Shanthie Mariet D’Souza eds., (New Delhi: Institute of Defense Studies and Analysis, 2009).

Carollee Bengelsdorf, Margaret Cerullo and Yogesh Chandrani eds., The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmed (Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Charles van der Leeuw, Oil and Gas in the Caucasus & Caspian: A History (UK: Curzon, 2000).

Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Power and Money (London: Freedom Press, 1992).

Daniel Yergin and Thane Gustafson, ‘Evolution of an Oil Rush,’ New York Times, 6 August 1997.

Dilip Hiro, Blood of the Earth: The Battle for the World’s Vanishing Oil Resources (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2008).

Dr Sarfraz Khan and Imran Khan, ‘Sino-Indian ‘Quest for Energy Security’: The Central-West-South Asian Geopolitical Turf — Dynamics and Ramifications’, Regional Studies, Volume XXVII, Number 2 (Islamabad: Institute of Regional Studies, Spring 2009), pp.46-93.

Energy Information Administration (EIA), Turkmenistan Energy Profile, The United States Department of Energy (US DoE), 18 January 2007.

EIA, Pakistan Energy Profile, US DoE, 19 November 2009.

Fiona Hill, ‘Beyond Co-Dependency: European Reliance on Russia Energy’, ES-Europe Analysis Series (Washington: The Brooking Institution, July 2005), pp.7.

Frédéric Grare, ‘Pakistan: The Resurgence of Baloch Nationalism’, Policy Brief, No.29 (Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 2006).

Gawdat Bahgat, ‘The Caspian Sea Geopolitical Game: Prospects for the New Millennium’, OPEC Review, Vol. 23, No. 3, September 1999, p.199.

Guo Xuetang, ‘The Energy Security in Central Eurasia: Geopolitical Implications to China’s Energy Strategy’, China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, Vol.4, No.4 (US: Central Asia-Caucasus Institute, 2006), pp.21.

India Infoline News Service, ‘India Much Behind Pak in Gas Network: ASSOCHAM’, Mumbai, 5 May 2008.

Imran Khan, ‘Central Asia: Energy Pipelines, or Economic Lifelines’, World Security Network, New York, 14 December 2005.

Jennifer DeLay, ‘The Caspian Oil Pipeline Tangle: A Steel Web of Confusion’, Oil and Geopolitics in the Caspian Sea Region, Michel P. Croissant and Bulent Aras eds. (US: Prager, 1999).

M. J. Gohari, The Taliban: Ascent to Power (US: The Oxford University Press, 2001).

Maqsudul Hasan Nuri, ‘The ‘Afghan Corridor’: Prospects for Pak-CAR Relations, Post-Taliban?’, Regional Studies, Volume 20, Number 4 (Islamabad: Institute of Regional Studies, Autumn 2000).

Martha Brill Olcott, ‘International Gas Trade in Central Asia: Turkmenistan, Iran, Russia and Afghanistan’, Working Paper 28, Baker Institute for Public Policy (Houston: Rice University, Houston, May 2004).

Mark Zepezauer, Boomerang!: How Our Covert Wars Created Enemies Across the Middle East and Brought Terror to America (US: Common Courage Press, 2002).

Michael Griffin, Reaping the Whirlwind: The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan (London: Pluto Press, 2001).

Michael T. Klare, Blood and Oil: The Dangers and Consequences of America’s Growing Dependency on Imported Petroleum (NY: Owl Books, 2004).

Michael Klare, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: How Scarce Energy Is Creating A New World Order (England: OneWorld, 2008).

Paul Thompson, Central Asian Oil, Enron and the Afghanistan Pipelines, Center for Cooperative Research, 2002.

Prof. Aftab Kazi, Geopolinomics of Transit Routes between Central Asia and South Asia, Public Lecture at Social Research Center (Bishkek: American University Central Asia, 20 December 2006), pp.8.

Prof. Paul Stevens, Cross-Border Oil and Gas Pipelines: Problems and Prospects, UNDP/World Bank, June 2003, pp.130.

Rahul Tongia and V. S. Arunachalam, Natural Gas Imports by South Asia: Pipelines or Pipedreams? (US:Carnegie Mellon University, September 1998), pp.48.

Ralf Dickel, Cross-Border Oil and Gas Pipeline Projects: Analysis and Case Studies, the World Bank, 5 September 2001.

Secretary of Planning and Development Division ‘National Energy Needs’, Pakistan Development Forum (Islamabad: Government of Pakistan, 26 April 2005), pp.20.

Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (US: Penguin Books, 2005).

Zia M. Khan, ‘Fearing Operation, Militants Flee North Waziristan’, The Express Tribune, 3 June 2010, Karachi, p.9.

* Imran Khan works as political analyst at the Australian High Commission in Islamabad, and is specializing in the geopolitics of pipelines and energy security in southern Eurasia. He holds an M. Phil. from Area Study Center (Russia, China & Central Asia) at University of Peshawar, Pakistan. His dissertation was The Trans-Afghan Oil and Gas Pipelines: Prospects and Impacts. This article is based on a paper the author presented at a Friday seminar at the Center on 10 April 2009.

An Italian emigrant to Argentina, Alejandro Angel, instituted a small oil company at Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1948. Carlos Bulgheroni, the company’s current chairman, and his brother Alejandro Bulgheroni, vice-chairman, elevated Bridas to being a leading oil- fields and wells- operating company in Latin America. After being ranked as the third largest company in Americas and 40 years of experience in the newly developed Argentinean energy industry, in 1978 Bulgheronis projected their business internationally. In recent years, the company sold shares of its regional and international operations to British Petroleum, Amoco and CNOC. For insights in the company’s owners and operations, see Ahmed Rashid, Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia (1999), p.157.

Michael Klare, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: How Scarce Energy Is Creating A New World Order (England: OneWorld, 2008), pp.1-8.

Khalilzad used the phrase in a speech given at John Hopkins University in Washington. See Asia News Channel <http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/afp_asiapacific/view/113912/1/.html>

Ahmed Rashid, The Resurgence of Central Asia: Islam or Nationalism? (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1994).

By 1900, Baku was the “emporium of East and West” energy economy, as eminent historian of the energy geopolitics Daniel Yergin puts it, for the region produced 51 percent of the world’s crude oil production in 1901. For more details and a historical narration see, Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Power and Money (London: Freedom Press, 1992); Charles van der Leeuw, Oil and Gas in the Caucasus & Caspian: A History UK: Curzon, 2000); Gawdat Bahgat, ‘The Caspian Sea Geopolitical Game: Prospects for the New Millennium’, OPEC Review, Volume 23, Number 3, September 1999, p.199.

For a comparative analysis of these geopolitical perspectives, see M. R. Ronald Hee, ‘World Conquest: The Heartland Theory of Halford J. Mackinder,’ Pointer, Volume 24, Number 3, July-September 1998 <http://www.mindef.gov.sg/safti/pointer/back/journals/1998/Vol24_3/8.htm>

Martha Brill Olcott, ‘International Gas Trade in Central Asia: Turkmenistan, Iran, Russia and Afghanistan,’ Working Paper 28, Baker Institute for Public Policy (Houston: Rice University, Houston, May 2004), p.17.

British Petroleum (BP), Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2007, quoted in Klare, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet, p.120.

For this episode in the making of a new energy world order, see Klare, Rising Power, Shrinking Planet, pp.1-6.

John Imle of Unocal in an interview with Ahmed Rashid in 1999 said his company “spent approximately US$15-20 million on the CentGas project. This included humanitarian aid for earthquake relief, job-skill training and some new equipment like a fax machine and a generator.” See Ibid, p.171.

Mark Zepezauer, Boomerang!: How Our Covert Wars Created Enemies Across the Middle East and Brought Terror to America (US: Common Courage Press, 2002), p.138.

For a description of resources wars, see Dilip Hiro, Blood of the Earth: The Battle for the World’s Vanishing Oil Resources (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2008); Michael T. Klare, Blood and Oil: The Dangers and Consequences of America’s Growing Dependency on Imported Petroleum (NY: Owl Books, 2004).

See Paul Thompson, ‘Central Asian Oil, Enron and the Afghanistan Pipelines’, Center for Cooperative Research, 2002 <http://www.911review.org/Wget/www.cooperativeresearch.org/timeline/main/AAoil.html>

For details, see Maqsudul Hasan Nuri, ‘The ‘Afghan Corridor’: Prospects for Pak-CAR Relations, Post-Taliban?’, Regional Studies, Volume 20, Number 4 (Islamabad: Institute of Regional Studies, Autumn 2000), p.34; United Press International, 27 December 2002.

ADB, Technical Assistance for the Feasibility Studies of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan Natural Gas Pipeline Project, TAR: STU 36488, December 2002, p.7.

Vice-President of Unocal’s exploration and production division, Marty Miller, believed “The Afghan pipeline project was, as Steve Coll reported him, “as a ‘no brainer’ if only ‘you set politics aside’.” For more details see, Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (The US: Penguin Books, 2005), p.305.

Marty Miller’s another pessimistic description of the TAP project, while appreciating the pipe-plan’s “romantic, grandiose scale”, as Coll puts it. For reference, see Ibid. p.303.

Rahul Tongia and V. S. Arunachalam, Natural Gas Imports by South Asia: Pipelines or Pipedreams? (US:Carnegie Mellon University, September 1998), p.48.

For a study of the problems of building and assessing pipelines see, Prof. Paul Stevens, Cross-Border Oil and Gas Pipelines: Problems and Prospects, a Joint UNDP/World Bank Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme (ESMAP), June 2003, pp.130. Also Ralf Dickel, Cross-Border Oil and Gas Pipeline Projects: Analysis and Case Studies, World Bank, 5 September 2001. For technical, logistic and throughput details, also see Tongia and Arunachalam, Pipelines or Pipedreams, pp.48.

For analysis see Imran Khan, ‘Central Asia: Energy Pipelines, or Economic Lifelines’, World Security Network, New York, 14 December 2005 <http://www.worldsecuritynetwork.com/showArticle3.cfm?article_id=12207>; Dr Sarfraz Khan and Imran Khan, ‘Sino-Indian ‘Quest for Energy Security’: The Central-West-South Asian Geopolitical Turf — Dynamics and Ramifications’, Regional Studies, Vol. XXVII, No. 2 (Islamabad: Institute of Regional Studies, Spring 2009), pp.46-93.

See Fiona Hill, ‘Beyond Co-Dependency: European Reliance on Russia Energy’, ES-Europe Analysis Series (Washington: The Brooking Institution, July 2005), pp.7 <http://www.brook.edu/fp/cuse/analysis/hill20050727.pdf>

For energy data of Turkmenistan see, Energy Information Administration (EIA), Turkmenistan Energy Profile, The United States Department of Energy (US DoE), 18 January 2007. <http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/country_energy_data.cfm?fips=TX>. For energy statistics of Pakistan see, EIA, Pakistan Energy Profile, US DoE, 19 November 2009 . <http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/country_energy_data.cfm?fips=PK>. Also see a presentation by then Secretary of Planning and Development Division, the Government of Pakistan, ‘National Energy Needs’, Pakistan Development Forum (Islamabad: 26 April 2005), pp.20.

As far as gas consumption, intensity and infrastructure is involved, Pakistan is well ahead of India. Gas consumption in India is limited to 20 major cities that are connected by a gas distribution a 10,500 kilometers pipeline grid. Density of the pipeline network is 116 kilometers per million metric standard cubic meters a day (MMSCMD). Pakistan, on the other hand, with 1,050 major cities and small towns connected to a 56,400 kilometers long gas distribution network, having a density of 1,044-km/MMSCMD. Of the total, 31,000-km pipeline is serving only domestic consumers. As a result, Pakistan has 1.9 million gas consumers as compared to India’s half-a-million. For details see, India Infoline News Service, ‘India Much Behind Pak in Gas Network: ASSOCHAM’, Mumbai, 5 May 2008 <http://www.indiainfoline.com/news/innernews.asp?storyId=66747&lmn=1>

Jennifer DeLay, ‘The Caspian Oil Pipeline Tangle: A Steel Web of Confusion’, Oil and Geopolitics in the Caspian Sea Region, Michel P. Croissant and Bulent Aras eds. (US: Prager, 1999), p.71; Alex Whiting, ‘Afghanistan Still the ‘Sick Man’ of Asia’, Reuters, London, 20 June 2005 <http://www.alertnet.org/thefacts/reliefresources/11192674179.htm>; also Angelo Rasanayagam, Afghanistan: A Modern History (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2005).

Khalilzad used the phrase in a speech at John Hopkins University, Washington. See Asia News Channel <http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/afp_asiapacific/view/113912/1/.html>

For the history and evolution of the Taliban movement in the trans-Afghan region and its impact on the region’s security, see M. J. Gohari, The Taliban: Ascent to Power (US: The Oxford University Press, 2001); Michael Griffin, Reaping the Whirlwind: The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan (London: Pluto Press, 2001); also Rashid, Taliban. And for recent developments and analysis following the ‘War on Terrorism’, see Ahmed Rashid, Descent into Chaos: The U.S. and the Disaster in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia (US: Penguin, 2008).

C. Christine Fair, ‘Pakistani Attitudes Towards Militancy in and Beyond Pakistan’, Saving Afghanistan, V. Krishnappa, Shanthie Mariet D’Souza eds., (New Delhi: Institute of Defense Studies and Analysis, 2009), p.116.

Zia M. Khan, ‘Fearing Operation, Militants Flee North Waziristan’, The Express Tribune, 3 June 2010, Karachi, p.9.

Ahmed Rashid, ‘Pakistan Crisis ‘Hits Army Morale’’, BBC News, 13 September 2007 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6978240.stm>; Ayaz Amir, ‘A Banana Republic without Bananas’, Dawn, Islamabad, 01 February 2002, p.7. For the Baluch resistance movement see, Frédéric Grare, ‘Pakistan: The Resurgence of Baloch Nationalism’, Policy Brief, No.29 (Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 2006).