Ancient Peshawar:

Historical Review of Some of its Socio-Religious and Cultural Aspects

(3rd BCE - 7th AD)

Syed Waqar Ali Shah*

India, due to its fertile soil and riches, had always remained a big source of attraction for the Western world in general and Central Asia in particular. Fortune seekers in the form of invading armies or individuals, from all around the world, repeatedly took the route of India to accomplish their unfulfilled desires. Looking at the topographical outlook of Central Asia (big deserts, and Mountainous ranges with less chances for cultivation) one can easily conclude that there were very less opportunities and means of subsistence for human kind. It was this factor that encouraged them to look and shift towards neighboring India known for its riches and opportunities at various phases of its history.

In all this story of need and greed, the location of Peshawar gave it a distinct status of its own. Being placed next to the famous Khyber Pass it turned out to be the resting place or abode of quite a good deal of visitors, travelers and invaders of India, and occasionally from India. People invading or moving towards India had to make use of this border town to re-energize and refresh themselves and their beasts for their onward move. All types of deficiencies were adequately met and taken care before the re-start of the journey. The interesting thing to note over here is that the number of visitors was never any problem for Peshawar. If, for individuals and smaller groups the town of Peshawar catered the needs, for large numbers and armies the whole of Peshawar valley opened its arms in reception. So space was never any issue, which made Peshawar a favorite and a place of choice for the invaders. This geographical and strategic status of Peshawar was there with it, in all phases of its history. For the sake of clarity it seems appropriate to mention that the focus of our discussion, in this paper, will be the activities in and around the city of Peshawar.

Peshawar was part of different Trans-Indian and Indian governments including Acheamenian, Macedonian, Mauryan, Greco-Bactrian, Saka, Sytho-Parthian, Kushan, Hepthalite, Turki Shahi and Hindu Shahi (870-1021 AD). With all those governments and setups Peshawar enjoyed status of either capital, local capital or an important post. It usually happened to be centrally located, in a sense that on both Indian and Central Asian sides it was governed by one authority. In the presence of some physiographical distinctions like being surrounded by mountain ranges and river Indus, which can conveniently serve as a natural boundary too, the worth of Peshawar was always exalted for the successful continuation of rule and authority in either direction. The study of history reveals that whenever there was a strong single government on both sides of Peshawar, its worth got multiplied both strategically and culturally. To the extent that at time it even wore the crown of government and authority by being the capital of those governments. It also happened to be and served as the center of cultural and philosophical moves like that of Buddhism, Gandhara Art and Islam. Peshawar not only accommodated and welcomed these new ideas and cultures but after being thoroughly tainted with those also provided an effective and successful base for their furtherance towards other directions. The promotion of Buddhism in Central Asia, and Islam in India owe much to the service of Peshawar.

Nomenclature and Location

There is a variety of names available for Peshawar linked with it for some distinct reason of their own. These include:

Parshapur (the land of Parshas on the basis of the long sway of Persians (Achaemenids) in this region); Pesh awardan, which in Persian language means the ‘one coming forth;’ Bashapur meaning the ‘City of the King;’ Munshi Gopal Das referring a tradition recorded by Hamdulah Mustawfi, the author of Nuzhatul Qulub credits Sassanian emperor Shahpur (240-73 AD), son of Ardeshir, for the reconstruction of Peshawar. It was because of this act of emperor Shahpur that the city is said to be named after him that with the passage of time became Bashapur (Peshawar). Posha-pura This name is taken from one earliest written record of Peshawar. It was inscribed on a rock, in Kharoshiti language, found at a place called Ara, near Attock dated 119 AD. Sten Konow argues that Posha represents Pushpa which means flowers in Sanskrit language. If this suggestion is accepted then the phrase Posha-pura would mean ‘The City of Flowers.’ Folusha: Buddhism comprises one significant part of the history of Peshawar. It was this Buddhist link that attracted visitors from different parts of the world, particularly China, to come and place their reverences to one of their holiest sanctuaries. Now these Chinese visitors and pilgrims to Peshawar were also responsible for minting some new names and pronunciations or expressions to the city. One such Chinese pilgrim Fa-hian who visited Peshawar in 400 AD recorded it as Fo-lu-sha. Another Chinese visitor to Peshawar, Hiuen Tsang (629-645 AD), calls it Po-lu-sha-pu-lo. The famous Muslim historian and geographer al-Masudi (871-957 AD), also known as the 'Herodotus of the Arabs' for he wrote a 30-volume history of the world, spelt Peshawar as Pershadwar. Purshawar or Purushavar: Abu Rayhan Al-Biruni (973-1048 AD), the Arab geographer and historian records two variants for Peshawar; Purshawar and Purushavar. The Peshawar Gazetteer records a Hindu tradition that the name Parashapur was after a Hindu king called “Purrus” or “Porus.” That Hindu tradition says that the name Peshawar has got its roots from that seat of government of Hindu king Purrus or Porus. However we could not substantiate with evidence the existence of any Hindu king with these titles from any other reliable source.

Location

Peshawar is located in the Northwest of India as well as Pakistan. At the moment it is the capital of Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa province of Pakistan. On the other hand this Peshawar title also stands for a larger land mass including all the territory in the valley of Peshawar. Peshawar valley comprises of five districts including Charsadda, Mardan, Swabi, Nowshera, and Peshawar, known for their fertility and produce. According to one estimate it covers an area of some 8,800 square miles, lying about 1,100 feet above sea level.

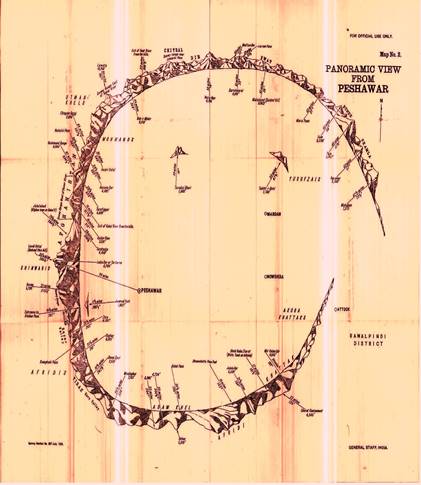

This Peshawar valley was protected from north, south and west, like a crescent, by mountains. The open end of this crescent of mountains, towards east, is covered by yet another natural boundary in the form of Indus River. Prof. Shafi Sabir relates the geography of Peshawar with a house having four openings. On the three mountainous sides of the valley there are passes which serve as doors of entry to it. In the north is the historical Malakand pass (Shah Kot). For long ages it has served as a route for travelers from Russia, China and Kashghar to Peshawar valley. In the south is the Kohat pass and in the west is the Khyber Pass. Khyber begins from the Tartara hills of the Suleiman Mountain. At places it is about a mile wide but at some places it shrinks to a mere few hundred yards. This narrow, rugged, barren and serpentine pass has romantic attraction for travelers and a peculiar attraction for one well versed in the military arts and affairs. Anyone coming from the eastern door is obstructed by the river Indus. In this way we find well defined boundaries of the valley of Peshawar being protected from all side by one strong natural defense system. (Map 1)

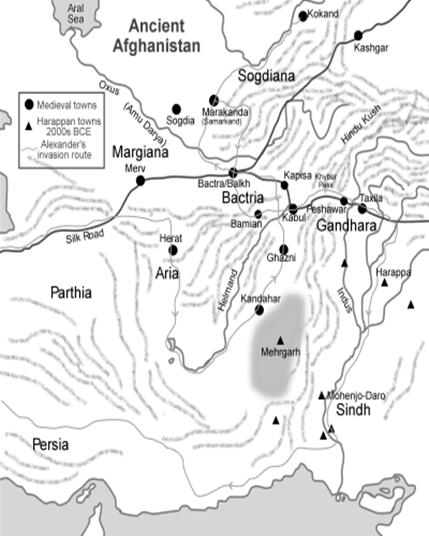

Top priority for any progressive military regime remains to secure the economic veins of any region. The topographical protections and natural fertility of the land with some exceptional irrigational blessings also rendered Peshawar a distinct enhanced status of its own kind. This status of Peshawar received one natural boost when turned out to be a part of the famous Silk Trade Route of medieval times. This proximity gave it a high status with the traders and trade caravans to meet and exchange their commodities here at Peshawar. Being a part of South-Central Asia it literally turned out to be one very important part of the famous Silk Route. (Map 2)

The geo-strategic importance of Peshawar can be judged from the fact that the Mughal King Humayun thought that if he can take control of Peshawar, he can easily control India. Even the British, for the protection of Peshawar, upgraded Nowshera, Kohat, and Jamrud etc. in terms of military oriented establishments.

Foundation of the City

Munshi Gopal Das in his book Tarikh-i-Peshawar (History of Peshawar) fixes the responsibility for the start or foundation of Peshawar to the Persian Achaemenids dynasty. According to him it was one Hoshang Pashedao, son of Siyamak and grandson of Kaiumars, who founded the city. When Hoshang entered eastern Afghanistan of which Peshawar Valley was also a part he found it under the control of some Hindu Raja Pardaman. Hoshang after getting control of the valley laid foundation of a city called ‘Farsawar’ which later on was known as Peshawar.

Hayat Khan in his book Hayat-i-Afghani (written in 1867) tells us that the city after being destroyed once was rebuilt on the same site by one Hindu Raja Bikram. The name of that Hindu Raja provided Peshawar with yet some other names in history. These names were Bikram or Bagram. This title of Bagram was used by Mughal King Babur and some Pushto poets like Khushal Khan Khattak, Rehman Baba and Kazim Khan Shaida. However, according to Hayat Khan the name given to it by that Hindu Raja was ‘Purshor’, which ultimately became Peshawar.

For the foundation of Peshawar Dr. Moti Chandra relates a story referred in a French work which says that ‘a deity in the form of a shepherd pointed to Kanishka a place where to rise the highest stupa of the world and the city of Peshawar was founded there.’ Now if we try to analyze this view of Dr. Moti that the city was developed around the stupa of Kanishka that happened to be quite distantly located in terms of time we will be required to ignore all the past references for the foundation of the city, which in my opinion would not be fair. Whatever may be the reality behind the real start of this city; recorded history tells us that the city we know today as Peshawar attained its actual fame and glory under the Kushans, a Central Asian tribe of Tohorian origin, somewhere over 2,000 years ago.

Peshawar as Part of Gandhara

Peshawar and the city of Taxila were the most significant cities of the kingdom of Gandhara. They happened to be the capitals of the different kingdoms of the past. Peshawar saw probably the best days of its prosperity and recognition due to being the center for some Indo-Greek, Scythian, Parthian, and Kushana empires. Besides socio-cultural advancement under those regimes it was blessed and beautified by nature through enchanting rivers, mountains, valleys and climate. Gandhari, the mother of the Kurus of the Epic Age who fought the Mahabharata war was the native of this region.

Gandhara Art

Gandhara art evolved in the Peshawar valley when it was ruled by the Kushan dynasty (200 AD). Being initiated and developed at Peshawar it was basically a merger of Greek, Syrian, Persian, and Indian artistic tastes. In Buddhism it got its strongest source or medium of expression. To the extent that there is a thought that the art was promoted and developed for the propagation and popularization of Buddhism through visual means among the masses. The art usually revolves around Buddhism and Buddha who is attended by gods and devotees in the panels. Various expressions of this art show the exalted and prominent position enjoyed by Buddha among other human beings. Each and every important scene belonging to the life of Buddha transformed to Gandhara Art.

Gandhara art entered upon a new phase with the coming of Kushana rulers in Peshawar (1st to 5th AD); particularly in its initial phase (75—225 AD) it crossed milestones of its history. As a matter of fact it was during the Kushana period that the unification of Gandhara art and Buddhism took place. The rise of Mahayana Buddhism during this period under the patronage of Kushan king Kanishka (128—151 AD) was one significant impact of this unification. For the first time ever in the history of Buddhism Buddha was represented anthropomorphically (in figure art). Under the patronage of Kushana rulers (1st-2nd Century A.D.) this new school of art flourished and received a great push in the Gandhara region, i.e. Peshawar and its surroundings. Because of the strategic geographical position of the region, the new discipline also started moving swiftly in all direction resulting in its introduction and establishment. This on its turn also gave way for the further extension of this art through mingling and interactions with foreign and other established ideas.

Buddhism in Peshawar

Buddhism was first founded in eastern India around 520 B.C. by Buddha (563-483 BC) and it reached Gandhara in the 3rd century B.C. courtesy to the excessive interest of Ashoka. King Ashoka provided the first royal patronage to Buddhism while king Kanishka provided the second royal patronage. The fifth of Ashoka's Edict at Shahbaz-Garhi indicates that Ashoka regarded Gandhara as a frontier country 'still to be evangelized'. According to Sinhalese chronicle the Mahavamsa, Gandhara was converted to Buddhism during Ashoka's reign by the apostle Madhyantika somewhere around 256 B.C. Gandhara received its second impetus towards Buddhism during the reign of great Kushan king Kanishka. With Gandhara being the center of his vast kingdom and his excelling dedication towards Buddhism an all impressive link of Peshawar and Buddhism was established. It turned out to be a landmark feature for both Peshawar and the religion. One can say that Peshawar enjoyed an all times high status and worth as a result of Kanishka’s commitment. On the other hand Buddhism also witnessed a rapid growth of it philosophy in all direction around Peshawar as a result of this interest of the sovereign. Slowly and gradually Gandhara attained a very high spiritual status amongst the Buddhist for it being the home of some of their monasteries and relics. One can even say that it became the 'second holy land' of the Buddhists frequented by the Chinese converts who were absolutely satisfied with the visit without making further pilgrimage to the Ganges basin. Hiuen Tsang in giving a picture of the Buddhist Gandhara relates that about a thousand Buddhist monuments existed in Gandhara alone.

Fourth Buddhist Council at Peshawar

The Buddhist activities started with full force in Peshawar when Kanishka became a Buddhist. It was from here that Buddhism travelled to Swat, Gilgit, Tibet, China, Afghanistan, Central Asia, Mongolia and the Far East. The next targets achieved by Buddhism happened to be Korea and then Nara in Japan, the country of Mahayana Buddhism. Kasyapa Matanga, a Buddhist missionary from India, went from Peshawar and introduced Buddhism in China somewhere about the first century AD while Asvaghosa and Nagarajuna stayed in it to compose the Mahayana Buddhist texts. Majority of the Buddhists of the world are Mahayanists. Kanishka fully patronized and propagated this sect of Buddhism. With Kanishka perched at the highest pedestal of government at Gandhara, the time was best ripe for any major show of Buddhism. Kanishka convened the fourth Buddhist Council (conference) in Gandhara, somewhere around the middle of 2nd century CE. Most probable venue for this congregation could be Peshawar, capital of the rulers, where once stood the great monastery and stupa of Emperor Kanishka. It was attended by about 500 monks, including Vasumitra, Asvaghosa, Nagarajuna and Parsava. Vasumitra was the President and Asvaghosa the vice President of the conference. It is said that the Mahayana Buddhism formally rose after this period. Voluminous commentaries on the three Pitakas were prepared. The entire Buddhist literature was thoroughly examined and the comments were collected in the book Mahavibhasha. The decisions of the conference were engraved on copper plates and deposited in a stupa specially built for this purpose. Taranath, the Tibetan historian informs us that the conference settled disputes between eighteen schools of Buddhism which were all recognized as orthodox. Kanishka planted the sapling of the Bodhi tree in Peshawar under which the Buddha had achieved the enlightenment at Bodh Gaya in India.

Buddhist Monuments in Peshawar

During the Buddhist period Peshawar was studded with a number of sacred structures – stupas and sangharamas (Monasteries)—which drew towards itself a number of travelers and turned it into a veritable place of pilgrimage for the followers of Buddha. Unfortunately most of these monuments have disappeared altogether, others are in the process of decay, and only a few have survived the ravages of time and man. Gor Khatree, Shahji Ki Dheri (Hazar Khani) Buddha’s Begging Bowl, Buddha’s Casket, Kanishka’s Monastery, Bodhi Tree (Pipal Mandi-Dhaki Nalbandi) etc are among some of the very famous and important Buddhist relics of Peshawar.

Brahmanical Religions in Peshawar

Religious history of the period reveals that despite the outstanding Buddhist influence upon the region Brahmanical religion in all its variety of sects was largely in vogue in those times. It so often challenged Buddhism in Peshawar. These Brahmins were responsible for the persecution of Buddhist in the history of this region. Somewhere in the 2nd century BC, when Pushpamitra overthrew Muriyan dynasty, he on the instigation of Brahmin priests persecuted the Buddhist, massacring their monks. Some popular Brahmin cults of the region were:

Shivaism was one popular religion at Gandhara centuries preceding the Christian era. This is supported by the archeological finds from the Sindhu Valley consisting of prototypes of Shiva as Pasupati and his emblem the Shiva-linga. Some early Greek writers like Strabo refer to the tribes of Punjab and Gandhara like Siboi and Oxydrakai as regarding themselves as descendants of Shiva. The early Indian coins hailing from Taxila bearing theriomorphic and anthropomorphic figures of Shiva also tell us for the popularity of Shivaism in this region. Similarly some coins of Indo-Greek king Demetrius who ruled in Gandhara around 200 BC bear the figure of Shiva’s emblem, the trident on the reverse. Even during the Kushan era at Gandhara Shiva succeeded in maintaining its distinct identity which is evident from the fact that the coins of the Kushana rulers like Kadaphises II, Kanishka, Huvishka and Vasudeva contain the figure of Shiva and his emblems like trident and the sacred bull.

In the post-Kushana rulers times Shivaism survived in Gandhara under Sassanian patronage. One gold coin, issued under the sovereignty of Shahpur I (AD 256-264) shows Shiva grabbed in Sassanian dress. Shivaism must have enjoyed an elevated status during the Hun King Mihirakula who was not well disposed towards Buddhism or Buddhists and was an ardent devotee of Shiva. The Chinese traveler Hiuen-Tsang has left account of two shrines related to the Shiva cult. One was situated on the top of a high mountain about 50 li or so to the north east of Polusha, modern Shahbazgarhi. The shrine was that of Bhimadevi, the consort of Ishvaradeva (Shiva). The other temple was dedicated to Mahesvaradeva at the foot of that mountain. These two shrines were very important in the 7th century AD and were “great resort of devotees from all parts of India.” In the Mahabharata we find a tirtha named Bhimdevisthana beyond Pancha-nada, in the account of various sacred places of India. It seems that this Bhimdevisthana of Mahabharata is actually the Bhimadevi shrine which Hiuen-Tsang is referring.

The discovery of Shiva-image (Mahesha also called Trimurti) from Charssada also tells us that Buddhism was not the only religion practiced at Gandhara. The deity is three-headed, three-eyed, and six-armed, and stands before the bull nandi, holding the damaru, trisula and kamandalu. The style is Indianised Gandhara art of the third century AD. Vasubandhu, a famous Brahman of Peshawar, tells us about two sects of Shivaism, Pasupata and Kapalika in the Gandhara.

One latest discovery and theory forwarded by M. Nasim Khan is regarding Gandhara being either the first or one of the earliest abode of Shivaism in India. His theory revolves round some of his discoveries made at a place called Kashmir Smast near Mardan. The icons, plaques and masks, ceremonial and other pots, moveable and immoveable inscriptions, seals and sealings, coins, jewellery and other personal ornaments found at the site ties its links with an altogether unknown past.

Another branch of Brahmanism known as Saktism was also quite popular in the Gandharan society. The places where the Devi or Sakti was worshiped were known as the Pitasthana. One such Pitasthan was situated at Peshawar that was visited by Hiuen-Tsang and mentioned as a great center of Saktism.

Karttikeya Worship

The inscription on the relic casket discovered at Shah-ji-ki-Dheri, outside Ganj gate of Peshawar shows that Karttikeya worship was popular with the Buddhists at the time of Kanishka. The inscription talks about some Mahasena that according to Sanskrit texts means Karttikeya. The discovery of some sculptural remains of god Karttikeya belonging to the earlier and later periods show that the worship of Karttikeya cult was strongly patronized by the local people of the region.

The Cult of Folk-gods

Worship of folk-gods was also practiced at Peshawar, from old times. Yaksha Puja was an important cult both in Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical faiths during the time under consideration. A detailed list of Yakshas who were associated with different places of North Western India is given in the northern Buddhist literature, Mahamayuri. The popular Yakshas of Gandhara were Pramardana and Vaikritika. According to a Parthian amulet a Yaksha named Bis-Parn occupied Puska-vur. Here Puska-vur is undoubtedly identified with the ancient Purushapura i.e., modern Peshawar. The Yaksha Bis-Parn has been identified with Visvapani, “the fifth of the Dhyani Bodhisattvas” in northern Buddhism. Though Peshawar or Purushapura is not mentioned in Mahamayuri list, Gandhara is referred twice. With the passage of time these Yakshas became famous as local gods and goddesses and some interesting myths and mythologies were created around them.

Sun Worship

The sun has been honored by number of old cultures. It was a source of power and energy, light and warmth. It was what made crops grow every season and promised prosperity to many. Some cultures went to the extent of adoration of it for its grandeur and excellence. We have not sufficient data to say with any certainty that how much sun worship was popular at Peshawar (Gandhara) in its earlier history. Nevertheless, there are certain archaeological findings that help us draw some image about it, based on documents. There are some coins issued by the Kushana Empire that bear the figure with the name Miiro (Mihiro) by its side. Similarly one of the white marble sculptures of the 5th century A.D. discovered from Khair-Khaneh in Afghanistan represents the solar deity and his acolytes. This is one most important sculpture that throws some light on the popularity of solar cult of the region in the post-Kushana period.

Peshawar in the Accounts of Chinese Travelers

Buddhism gained grounds in China due to the missionaries sent from Peshawar. This was the reason why Peshawar attained a sacred position for the followers of Buddhism and pilgrims from near and far visited the holy places located here. The account of these travelers is an important source for the writing and rewriting of the ancient Indian history/ Pakistan history or Peshawar history. These foreigners included Koreans as well as Chinese, mostly the followers of Buddha. Though they came here probably for obtaining knowledge and enlightenment about Buddhism but their records also furnish with some really valuable information about the land, its geography and politics. The visitors included Fa Hien, Song Yun, Huan Tasang and Huei-ch-ao. They have left some valuable information about the city and its surroundings. Of all the visitors Huan Tsang sharing of geo-political environment of Gandhara and its surroundings is more extensive and valuable.

The first Chinese traveler to come to this region was Shi Fa-Hien. He came to Peshawar in the beginning of fifth century AD. He was a Buddhist monk and belonged to a place in China called Shansi and later went to Changan to study Buddhism. However, he was never satisfied with the material available over there. This led him along with some of his colleagues to undertake a journey to India in search of books which were not available and known in China. This coming and search of Fa Hien at Peshawar also leads us to conclude that this region was enjoying a unique reputation for its knowledge and learning in the Buddhist world of that time. Fa-Hien left Changan in AD 399 for India. During his stay in India he kept an accurate record of day-to-day knowledge which later composed the history of his travels. He returned to china in 414 AD and died at the age of eighty-six, in the monastery of Sin at King-Chow.

Fa-Hien left some very interesting information about Peshawar. He calls it Fo-lu-Sha and makes a distinction between Gandhara and Peshawar. For him Gandhara stood for Pushkalavati (Charsada) and he does not say that Peshawar was the capital, either in Kushan or earlier times. Fa-Hien also tells us about some relics and religious places of Buddhism at Peshawar. These included the stupa of Kanishka at Shahji-ki-Dheri, and the begging bowl of Buddha. For the stupa he said that it was 400 feet in height and “adorned with all manners of precious things.” For him it was superior to all other “topes” in ancient India, both in height and beautification. About the begging bowl he says that it was placed at a stupa served by more than 700 monks. The place was called Patra Chitaya and the begging bowl long remained enshrined there in a vihara.

The next Chinese visitor to Peshawar was Hwai Sang who came here in 500 AD. However, he is reported to have left less account of the city. Next in 518 AD another Chinese traveler Sung Yun visited the kingdom of Gandhara. From his record we learn that the kingdom of Gandhara was at war with the king of Kabul. At the time of his visit the Huns were enjoying authority in the region and he thought that they were responsible for the destruction of Buddhism. About the common people he says that they were Brahmans and had great respect for the law of Buddha.

The important and rich in information, about the city, of all these visitors was the visit of Hiuen Tsang. He visited Peshawar in the seventh century (somewhere in between 629-645 AD) and found the towns and villages deserted with few inhabitants. He left a valuable account of his travel.

The kingdom of Gandhara is about 1000 li from east to west, and about 800 li from north to south. On the east it borders on the river Sin (Sindh). The capital of the country is called Po-lu-sha-pu-lo; it is about 40 li in circuit. The kingdom is governed by deputies from Kapisa. The towns and villages are deserted, and there are but few inhabitants. At one corner of the royal residence there are about 1000 families. The country is rich in cereals, and produces a variety of flowers and fruits; it abounds also in sugarcane, from the juice of which they prepare “the solid sugar.” The climate is warm and moist, and in general without ice or snow. The disposition of the people is timid and soft; they love literature; most of them belong to heretical schools; a few believe in true law. From old time till now this borderland of India has produced many authors of Sastras; for example, Narayanadeva, Asanga Bodhisattva, Vasubandhu Bodhisattva, Dharmatrata, Manorhita, Parsva the noble, and so on. There are about 1000 Sangharamas filled with wild shrubs and solitary to the last degree. The stupas are mostly decayed. The heretical temples, to the number of about 100, are occupied pell-mell by heretics.

Hiuen Tsang also tells something about any “royal residence.” It was a fortified or walled portion of the town, in which the Palace or the Royal Residence was located. Dr. Dani thinks this place to be comprised of area including the present Bala Hisar and Andar Shahr, surrounded and protected by Bara River at that time. Hiuen Tsang then gives account of some Buddhist sacred places like his begging bowl placed near Panj Tirath and the Pipala tree with its unique height (100 feet) and spreading branches. About Kanishka’s stupa at Shahji-ki-Dheri, he says that it was approximately 400 feet high and had large quantity of Buddha relics. To the west of this enormous stupa Kanishka also built a monastery. It was a two story building but was in much ruined form. Nevertheless, some monks were still there who professed Mahayana doctrine of Buddhism. His description of number of Buddhist stupas and Buddha's statues shows the archeological richness and importance of Peshawar with regards to Buddhism at that time.

The history of Peshawar is studded with multiple political and socio-cultural land marks. It had a note-worthy identity for the travelers and invaders, to and from India. Even the socio-cultural drives in India and Central Asia did not fail to consider for that worth. Peshawar witnessed some intensive military, literary, economic, ideological and other cultural activities at various phases of its history. However, due to some negligence on the part of recorders of history and also due to some non-conducive political environments, a good deal of multiple facets of its history needs to be restructured for the fair understanding of those missing links. The level of involvement of some high profile and well known political entities of their time on both Indian and Central Asian sides of Peshawar tells us about its strategic worth for them. They not only used it as an effective military base but also invested in its socio-cultural and economic arenas for the multiplication of their returns. Even today it is one vibrant hub of socio-political and economic activities of the region. One tangible irony of its history happens to be that this blessed status of strategic worth at times turned out to be a curse. The power centers in the surrounding or even located distantly in order to minimize chances of success of their opponents fell severely upon it causing repeated devastations and destabilizations of it. Keeping in view its established worth it is important that the region be paid extra ordinary attention for its security and effective positive role in the growth and development of itself and its environs.

Map 1: Valley of Peshawar

After: The Gazetteer of Peshawar District 1897-98

Map 2: Peshawar linked with Silk Route

After:http://www.palden.co.uk/palden/p4-afghanistan.html Retrieved on 16/5/2010

Bibliography

Al Beruni, Kitabul Hind. tr. E.C. Sachau, Alberuni's India, Vol. I, Lahore: Sh. Mubarik Ali, 1962.

Banerjee, J.N. Development of Hindu Iconography. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1974.

Banerjee, Radha. “Buddhist Art in India”, Kalakalpa. Journal of Indra Gandhi National Institute of the Arts. http://ignca.nic.in/budh0002.htm retrieved on 20/10/07.

Bidari, Basanta, Lumbini, Past Present and Future with Master Plan. Singapore: 2000.

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 1946-48, vol-XII

Cunningham, Alexandar. The Ancient Geography of India, The Buddhist Period. Varanasi: Indological Book House, 1963.

Dani, Ahmad Hassan. Peshawar: Historic City of the Frontier. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel, 1995.

Das, Munshi Gopal. Tarikh-i-Peshawar. Lahore: Globe Publishers, N.D.

Deambi, B.K. Kaul. History and Culture of Ancient Gandhara and Western Himalayas: from Saradha epigraphic sources. New Delhi: Ariana Pub. House, 1985.

Foucher, Alferd. Buddhique du Gandhara, tr. L.A. Thomas & F.W. Thomas, The Beginnings of Buddhist Art, London: H. Milford, 1917.

Goswami, Jaya. Cultural History of Ancient India (A Socio-Economic and Religio-Cultural Survey of Kapisa and Gandhara). Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1979.

Hasan, Mahmood ul. ‘The Pleistocene Geomorphology of the South-Eastern Part of Peshawar Vale’ PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, University of Peshawar, 1995.

Herzfeld, E. Kushano-Sassanian Coins, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India. No. 38, Coin # 7.

Ihsan H. Nadiem, Peshawar: Heritage, History Monuments. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2007.

Jaffar, S.M. Peshawar: Past & Present. Peshawar: S.M. Sadiq Khan Publisher, 1946.

Jenkins, Palden. Afghanistan: From Healing the Hurts of Nations. http://www.palden.co.uk/palden/p4-afghanistan.html Retrieved on 16/5/2010.

Khan, Muhammad Hayat. Hayat-i-Afghani. tr. Major Henry Priestly, Afghanistan and its Inhabitants, Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 1999.

Khan, Muhammad Nasim, Treasures from Kashmir Smast (The Earliest Shaiva Monastic Establishment). Peshawar: 2006.

Konow, Sten. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. II, Kharoshthi Inscriptions. Calcutta: Govt. of India, Central Publication Branch, 1929.

Marshall, John Hubert. Archaeological Survey of India. Annual Report, 1913-14, New Delhi: Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, 2002.

Moti Chandra, Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1977.

Mukherjee, B.N. ‘Nanā on lion: a study in Kushāṇa numismatic art.’ Journal of Asiatic Society, vol. XIII, No’s 1-4, Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1971.

Quddus, Syed Abdul. The North West Frontier of Pakistan. Karachi: Royal Book Company, 1990.

Rajagopalachari, Chakravarti. Mahabharata. New Delhi: Hindustan Times, 1950.

Sabir, Muhammad Shafi. Story of Khyber. Peshawar: University Book Agency, 1966.

Sehrai, Fidaullah. “Peshawar’s Buddhist Past”. Dawn Magazine 6th March 2005.

Sehrai, Fidaullah. Hund: The Forgotten City of Gandhara. Peshawar: Peshawar Museum, 1979.

Sehrai, Fidaullah. The Buddha Story in Peshawar Museum. Peshawar: Peshawar Museum, 1978.

Smith, V.A. Coins of Ancient India. Delhi: Indological book House, 1972.

The Gazetteer of the Peshawar District, 1897-98. Compiled by Punjab Government, Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 1995.

Tsiang, Hiuen. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World. (tr.) Samuel Beal, vol. 1, Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, 1969.

Watters, T. Yuan Chwang’s Travells in India. London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1904.

Whitehead, R.B. Catalogue of Coins in the Punjab Museum. Varanasi: Indic Academy, 1971.

Zwalf, W. The Shrines of Gandhara. London: British Museum, 1979.

* Asstt. Prof., Department of History, University of Peshawar.

Sten Konow, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. II, Kharoshthi Inscriptions. (Calcutta: Govt. of India, Central Publication Branch, 1929), 165.

Hiuen Tsiang, Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, (tr.) Samuel Beal, vol. 1, (Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, 1969), XXXII.

Alexandar Cunningham, The Ancient Geography of India, The Buddhist Period, (Varanasi: Indological Book House, 1963), 12.

Al Beruni, Kitabul Hind, tr. E.C. Sachau, Alberuni's India, Vol. I, (Lahore: Sh. Mubarik Ali, 1962), 276.

The Gazetteer of the Peshawar District, 1897-98. Compiled by Punjab Government, (Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 1995), 44.

Mahmood ul Hasan, ‘The Pleistocene Geomorphology of the South-Eastern Part of Peshawar Vale,’ PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, University of Peshawar, 1995, 13.

Muhammad Hayat Khan, Hayat-i-Afghani, tr. Major Henry Priestly, Afghanistan and its Inhabitants, (Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 1999), 34.

Dr. Moti Chandra, Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India, (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1977), 9.

Ihsan H. Nadiem, Peshawar: Heritage, History Monuments, (Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2007), 45.

Radha Banerjee, “Buddhist Art in India”, Kalakalpa, Journal of Indra Gandhi National Institute of the Arts. http://ignca.nic.in/budh0002.htm retrieved on 20/10/07.

Alferd Foucher, Buddhique du Gandhara, tr. L.A. Thomas & F.W. Thomas, The Beginnings of Buddhist Art, (London: H. Milford, 1917), 21.

BK Kaul Deambi, History and Culture of Ancient Gandhara and Western Himalayas: from Saradha epigraphic sources. (New Delhi: Ariana Pub. House, 1985), 86-7.

E Herzfeld, Kushano-Sassanian Coins, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, No. 38, Coin # 7.

John Hubert Marshall, Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report, 1913-14, (New Delhi: Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, 2002) P1. LXXII.

Jaya Goswami, Cultural History of Ancient India (A Socio-Economic and Religio-Cultural Survey of Kapisa and Gandhara), (Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, 1979), 51.

Muhammad Nasim Khan, Treasures from Kashmir Smast (The Earliest Shaiva Monastic Establishment), Peshawar: 2006.

B.N. Mukherjee, ‘Nanā on lion: a study in Kushāṇa numismatic art.’ Journal of Asiatic Society, vol. XIII, No’s 1-4, (Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1971), 192-93.