MIR MUNSHI AALA SULTAN MUHAMMAD KHAN AND HIS SERVICES TO AFGHANISTAN

Sarfraz Khan* Noor Ul Amin**

Abstract

This paper aims to examine life, works and services of Mir Munshi Aala Sultan Muhammad Khan for the development of Afghanistan. A well versed man in Persian (Dari) and English invited by the Afghan Government to assist the Amir Abdur Rahman to run the affairs of the state, especially, to translate correspondence of the Amir with the British Indian Government. He offered invaluable services towards constitutional development in, bringing political stability to, and strengthening Independence of Afghanistan by adeptly assisting Amir in negotiating Afghan borders with her neighbors. Sultan Muhammad Khan authored/edited several books, contributing towards Constitution making road map and state affairs of Afghanistan. He had to flee Afghanistan, following successful conspiracies in the Court of Amir, in Kabul, dubbing him a British government’s spy. He was subsequently imprisoned in Lahore by the British Indian government. His friendship with the royal physician, a British lady, Dr. Lillias Hamilton, enabled his release from jail. His services as Afghanistan’s Ambassador in England were also significant.

Key Words: Early life, Mir Munshi Aala in Afghanistan (Chief Secretary), British spy or Afghanistan’s spy, Ambassador to England, a lawyer from Christ’s College, Cambridge, his works as well as Dr. Lillias Hamilton’s novels, sons of Sultan Muhammad Khan.

Introduction

Afghanistan found itself caught between two great rival powers, i.e., British Imperialism in India and Czarist Russia, during the ‘Great Game’, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Afghanistan needed a ruler, who could secure and safeguard her interest, despite presence of both imperial powers and their covert and overt activities to subdue Afghans. Amir Abdur Rahman (r. 1880-1901), following death, in 1863, of his grandfather, Amir Dost Muhammad Khan (r.1826-39 and 1845-63) had to fight numerous wars of succession to secure throne of Afghanistan. Banished from Afghanistan in 1868, he took refuge in Tashkent, till he returned to northern Afghanistan in March 1880 and recaptured Afghan throne, in 1880, with the support of the British. After a great loss and bloodshed during fratricidal wars, Abdur Rahman successfully established a government in Afghanistan. Later Afghanistan became a buffer, between two rival imperial powers. Amir Abdur Rahman in Afghanistan raised a standing army to quell internal rebellion and strengthen the country in face of external agression. He was also able to dilute influence of the liberals over the state by intimidating and deporting political rivals. In 1880s, thousands of Kandahari families left for Persia along with Sardar Muhammad Yaqub, victor of Miawand. Other political deportee families included: Charkhi, Tarzi, and Musabeheen/Yahya Khels. They departed for India and Ottoman Empire from Afghanistan, in fact, were exiled by Amir Abdur Rahman.

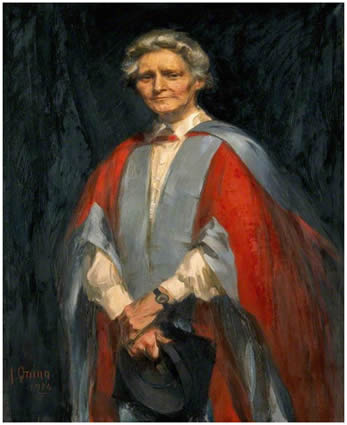

Amir Abdur Rahman demarcated Afghan boundaries with the Czarist Russia, in 1885 and with British India, in 1893. Inside Afghanistan, he introduced various reforms to develop Afghan society. The Amir hired various people from diverse regions and held periodic consultations with them. Such consultants included: Dr. John Gray (1857-1929), an English Physician from British India; Dr. Lillias Anna Hamilton M.D., (1858–1925), an English pioneer female doctor, successor to Dr. John Gray as court physician (1894 to 1898) of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan; Munshi Abdur Razaq of Delhi, a well-known printer; Chaudhry Sultan Muhammad Khan (1862-1931), a translator, secretary and Ambassador from Punjab and Dr. Abdul Ghani (1864-1943) later founded Habibia School, his brother Najaf Ali (1860-1949) translator and sub-editor. Dr. Lillias is also known for authoring two novels on Amir Abdur Rahman, one published in 1900, the second, unpublished, still lying in India office record. Sultan Muhammad Khan wrote several books and worked on highest positions in royal Afghan administration.

Early Life

Information on the early life of Sultan Muhammad Khan is scanty. One of the most important sources has been writings and speeches of his son, the renowned poet, Faiz Ahmad Faiz. The book compiled and edited by Sheema Majeed, Culture and Identity: Selected English Wirtings of Faiz. Oxford university press, USA 2006 sheds some light on the subject. Vassilyeva, Ludmila Alexandrovna in her book ‘Pervarish Loho Qalam, Faiz Hayat aur Takhliqat’ (Nurturing Tablet and Pen, Faiz Life and Works Oxford university press Karachi also devotes some space to it. Rashid Hameed’s article in Urdu, Faiz Ahmad Faiz ‘Sawanhi Khaka’ (Life Sketch), Saleem Ahmad’s article written in Urdu, ‘Kala Qadir ka Chervaha’ (Shepherd of Kala Qadir) and an article published in The Daily Dawn, on 11 Feb. 2011 on Centenary Celebration of Faiz Ahmad Faiz also briefly point towards life of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s father, Sultan Muhammad Khan, son of Sahib Zada Khan.

They agree that Faiz’s father was a landless peasant, employed by land owning peasants, to cater to their cattle, in a village, Kala Qadir, named after two poor brothers, Kala and Qadir, in District Sialkot. ‘I used to take the cattle out of the village and I found there was a school, a little distance from the village. I would leave the cattle to graze and attend the school’ Faiz quotes his father.

Acknowledging his inherent capacity instantly, his village school teacher not only allowed him to attend his class but also encouraged him to continue studies. This became a daily routine, he took the cattle out to graze, left them a while in the field, reached school for previous day work to be checked and get work assigned for the day, and return back to his cattle. He progressed swiftly and passed his village school examinations in 1873 ahead of all the other children. He earned a scholarship of two rupees a month, of Education Department Govt. of Punjab. He was admitted, in 1874, to Govt. High School at a distance from his village. He had to walk back and forth to school covering long distance during inclement weather. He passed High School examination in 1880 with distinction. During studies he assisted lawyers at the district Courts to pay for his expenses. He earned fame as the “educated” son of the village.

Sultan Muhammad Khan had been good looking intelligent, polite young man. Easy going as he was earned him friends every where and he survived in all sorts of company. After completing education at Sialkot in 1883 he continued higher education at Lahore and found abode free of cost in a local mosque. His voice was soft and fit for ‘qirat’ (reciting Quran), hence, began delivering private recitations of the Quran. After his studies and return in the evening to the mosque instead of resting, he fulfilled any task apportioned to him. Moreover, he worked at Lahore Railway Station as a ‘coolie’ (porter) to earn additional income to support his family back home in the village. He was untiring to the extent that hard labour could not be lower his interest in education. He demonstrated extra ordinary ability in learning languages and developed fluency in English and Persian, the two leading languages of the region besides the local Urdu. Sultan Muhammad Khan developed grip over Persian and English at school, in the evening he attended mosque to learn Arabic and religion. Sardar Amir Muhammad,Councilor of Afghanistan came to offer Juma prayer in the Hind Sharif Mosque. After Juma prayer, Sultan Muhammad Khan held conversation, both in Persian and English, with Afghan Councilor and immensely impressed him, this eventually led to his hiring by the Afghan Councilor to translate documents of Persian into English.

Departure to Afghanistan

Faiz described the scene, ‘when he (Sultan Muhammad Khan) was living in this mosque, it so happened that an Afghan grandee was Counsel to the Government of the Punjab. He used to come and pray in this mosque. He saw this young boy and rather liked him and said, ‘Look, we want an English interpreter for Afghanistan”. It shall be taken into account that the Afghan Amir, at that time, was trying to establish closer links with the rulers in British India in order to consolidate his own rule in Afghanistan. Anyone who could assist in furthering this goal was welcomed as friend. Therefore, Afghan Councillor offered Sultan Muhammad Khan briskly an appointment to tutor his own household, in English, initially. Later, in 1888, Afghan councilor took Sultan Muhammad Khan to Afghanistan and introduced him to Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman Khan. The Amir offered him a job of translator in his court. He was to translate documents and letters written in Afghan Persian (henceforth, Dari) of Amir into English and letters written in English to Amir into Dari.

It may be safely assumed that anyone fluent in English and Dari, who could assist in mediation and negotiations with the British was considered a valuable asset by the Afghan rulers. This fluency in English and Dari and hardwork earned Sultan Muhammad Khan eventually the position of the Mir MunshiAala (Chief Secretary). He ably performed the job of Royal interpreter conducted all correspondence and negotiations with the British.

These were tumultuous times in Afghan history, rival competing powers, Czarist Russia and British India, both were busy in power game, intrigues and spreading rumours inside and outside Afghan court. There were rumours that Amir was severely ill and suffered from deadly disease which has adversely affected his mobility. Though Amir’s sickness did generate numerous rumours amongst Afghan courtiers and much discussion in India, Britain and Russia, Sultan Muhammad Khan, in his official “biography” of Abdul Rahman Khan, barely makes a passing reference to the Amir’s sickness. It is evident that the secretary, witness to Amir’s frequent attacks of “gout”, did not disclose to neither Amir’s own subjects nor Britain or Russia, how severely ill Amir had been. Amir’s immobility and worsening mental condition subjected him to hallucinations, paranoia, mania and other psychotic disorders directly affected internal and foreign policy of Afghanistan. Relevant quarters, both internal and external, could be encouraged to depose him and replace by someone qualified better mentally and physically, to protect British interests in the region.

The illness of Abdur Rahman Khan has been recounted by two British physicians, John Alfred Gray and Dr. Lilias Hamilton who recurrently attended the Amirduring 1880s-90s. John Alfred Gray in, At the Court of the Amir: a Narrative (1895), 1st addition and My Residence at the Court , refers to Amir’s illness, diagnoses, and symptoms. Hamilton, though wrote two novels about Amir of Afghanistan: A Vizier’s daughter; and The Power that Walks in Darknesses, did not mention Amir’s illness in either. She did not record any memoirs of the time she spent in Kabul, however, upon her return to England, in 1898, she extensively delivered talks on Afghanistan and did publish short articles in British journals and magazines, where she spoke about Amir’s illness. Sultan Muhammad, at the court of the Amir, met and befriended Dr. Lillias Hamilton, the court physician, a British Lady, in the service of the Amir. In addition, numerous other Europeans and Afghans at the Amir’s court published details of the king’s sickness, or reported privately to the government in India on his condition, albeit from a layman’s view point.

Dr. Gray reported, in 1888, that Amir suffered a “long and severe” attack of “gout”, the worst and most prolonged period of sickness that Abdur Rahman Khan had ever experienced i.e., for nearly six months. The Amir did not wish anyone, except his most intimate advisors and family, to observe impact of disease on him including: his physical inaction; periods of unconsciousness, and disturbed mind. His secretary was able to cover Amir’s illness, though rumours still spreaded and remained in currency. Growing belief in Amir’s death or incapacity encouraged rebellion in Afghan Turkistan, leading to proclaimation of Amir,in Mazar-i-Sharif, of Ishaq Khan, son of the former Afghan Amir, “Azam Khan. This compelled Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, in December 1888, to write to the Viceroy in India to replace English physician, Dr. Gray, ostensibaly by a “gout” specialist. It seems Sultan Muhammad had gradually earned Amir’s trust, owing not only to hard work but also by keeping confidencial his diseases and his tactics during parleys with British India. He rose to the position of Chief Secretary (Munshi Aala) in 1892 and entered into wedlock with the niece of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan.

Afghan courtiers, felt annoyed and fearful of Sultan’s growing stature and influence and conspired to create rift between Amir and non- Afghan Sultan Muhammad, but Amir paid no attention to their complaints knowing his competence. The year 1893 marks beginning of Joint British-Afghan demarcation survey that covered 2450 km long border known as Durand Line eventualy resulted into buffer zone between “Great Game” rival British and Russian interests in the region. Following paragraph can provide ample evidence to Amir’s depth of trust in Sultan Mahomed Khan:

“I had arranged for Mir Munshi Sultan Mahomed Khan to sit behind a curtain without being seen or heard, or his presence known of by anyone else except myself, to write down every word they spoke to me, or among themselves, either in English or Persian. He wrote in shorthand every word uttered by Durand and myself, and this conversation is all preserved in the record office.”

The Amir conducted most vital negotiations to demarcate borders and define fate of his country with Sultan’s assistance. The inclusion of Sultan Muhammad Khan into inner circle of Amir can be further substantiated by the following excerpt from Amir’s biography where he talks about return of Durand’s Mission. “Two days before their departure all the English members of the Mission, together with Abdur Rahim Khan (their Oriental Secretary), Afzal Khan (British Agent at Kabul), and Nawab Ibrahim Khan, were invited by my son Habibullah to dine with him in the Baber Gardens. They were there received by my sons Habibullah and Nasrullah, and by Ghulam Haidar Khan (Commander-in-Chief), Mir Munshi, and two or three of my officials.”

The following excrepts may give reader the idea and nature of conspiracies prevalent at Amir’s court:

In 1894, Dr. Hamilton a replacement of Dr. Gray arrived in Kabul from India and attended him during the worst part of Amir’s illness. His hand caused substantial pain and the Amir had ordered many executions and confiscations of property. After examining Amir she realized, “his was not a trouble for which I could treat him single-handed or for which, indeed, he could be treated successfully under any circumstances in Kabul. He was suffering from a disease which must, I knew, eventually be fatal”. The appearance of blood in the urine, for her, pointed towards “haemorrhage” of kidneys,. The native hakim, fearing Amir’s imminentdeath and mindful of his own life, blamed Hamilton’s prescriptions for patient’s turn to worse, result of her medicines. Hamilton reported grave nature of Amir’s illness to Salter Pyne (1860-1921), another European in Kabul who at that time was acting as a secret news gather for the British government. This can be verified by urgent telegram informing Calcutta that the Amir was “hourly expected to die” from a “haemorrhage of the kidney”. Hamilton’s life was in danger due to successful intrigues of the Amir’s native hakim. She believed that in case of Amir’s death, she will face execution or imprisonment on the charge of poisoning the Afghan ruler. She kept a fast horse tethered near the entrance to the palace to flee, in the event of the Amir’s death till. Habibullah, Amir’s son personally reassured her and pledged his protection to Hamilton in case of his father’s death.

Hamilton had been very close and affectionate to Sultan Muhammad Khan; was well aware of the conspiracies hatched by the courtiers; advised him “to be aware about the changing situations and moodes of the rulers”, she elaborated that today’s “kind King might be cruel tomorrow”, what was in hand of him had to be saved. Thus, Sultan heeding her advice transferred all his wealth abroad through her and she became his finance minister. Alarmed,, in 1897, sensing changed situation of the court,Sultan Muhammad Khan decided to flee Afghanistan. Along with Imam Bakhsh, his guard,at night, he swiftly but secretly left for Hindustan on horse’s back. Upon arrival at Lahore, he was arrested by the British officials and put into jail. Wondered Sultan Muhammad Khan, “why he was sent to Jail”? He was arrested as an Afghan spy and placed in custody in the same Lahore fort where Faiz Ahmad Faiz was to be imprisoned many years later. Sultan Muhammad could secure his release from British government’s jail through good office of Dr. Hamilton.

There exists general agreement that Sultan Muhammad earned trust of the Amir and also wrote Amir’s biography, “The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman vol: I & II ’, there is disagreement about his departure from the Afghan court. One version, more widely believed that the increased trust of the Amir upon his Chief Secretary, invited jealousy and envy against him since he was not an ethnic Afghan and had no family or other connections within the court (his wife, niece of the Amir, died within two years of his marriage). He fled Afghanistan following warning of intrigues against him and on advice of Dr. Hamilton. She agreed to transfer his accumulated wealth to London in her name.

Another plausible reason of Sultan Muhammad departing the Afghan court can be that the Amir appointed him Ambassador to England due to his meticulous service during parleys with Durand’s mission, confidentiality, intelligence and faithfulness. Whatever the situation, before 1898. Sultan Muhammad left Kabul and after a brief stay in Kala Qadir, proceeded to United Kingdom. There, in addition to his duties as the Ambassador of the Amir of Afghanistan to the British Court, he also got himself enrolled at Cambridge University to earn a law degree. Sultan Muhammad had previously been working on the Dari version of the Amir’s biography which the Amir personally had partially dictated to him. The English version was published, in 1900, entitled, The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman Vol.1 & Vol.2 in haste since the Amir was extremely ill at this time.

British Indian Government on the other hand had been considering him an Afghan agent, a spy. The report was based on Sultan Muhammad Khan’s interview granted to Sir Salter Pyne in1896-7 stating he had "fled" Afghanistan to avoid the Amir’s wrath and eventually spent some time in London. It was only after his return to India a few years later that it was clear that he had been acting as the Amir's agent all the time.

Meanwhile, the younger cousin brother of Sultan Muhammad Khan, Nabi Bakhsh, the Principal of Islamia College Lahore (1892-1898) introduced Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam Punjab, Lahore to the Government of Afghanistan, during reign of Amir Abdur Rahman. In April 1895, Sultan facilitated his visit to Afghanistan to collect financial assistance for the Anjuman. He stayed seven days as state guest with prince Nasrullah Khan, son of Amir Abdur Rahman. His salary and travel expenditures were paid by Afghan host. On 1st October, 1895, Prince Nasrullah Khan proceeded to England via Lahore; and donated Rs.1000 to the Anjuman.

In United Kingdom

Upon release from Lahore Fort, in 1897, Sultan Muhammad Khan decided to visit United Kingdom and secured admission in Bar at Law at Cambridge University. Amir Abdur Rahman found out that “the gentleman is now in Christ’s College, Cambridge University” and he appointed Sultan Muhammad Khan Ambassador of Afghanistan to United Kingdom, in London,. Hence, in 1898, Sultan Muhammad Khan became the Ambassador of Afghanistan in London. He served in this capacity for three years; and also completed his Bar at Law there. Sultan Muhammad continued his service as Ambassador after death of Amir during reign of new Amir Habibullah in 1902-1905 too. In London, Sultan Muhammad had opportunities to meet Indian noted Muslim personalities from India such as Allama Iqbal (1877-1938), Sir Shafi (1869-1932), Sir Fazal Hussain (1877-1936) and Sir Abdul Qadar. He began practice as a Barrister in London in 1905 and continued till 1907. He decided to return to his native village in 1908, voyaged from England to Bombay and by train to Lahore and Sialkot. He had been in Sialkot and began practicing law and also married fifth time. Sultan Muhammad was awarded the title of ‘Khan Bahadur’ in 1908 by the crown. His Afghan wives finally joined him in Sialkot too. Youngest wife, barely older than some of his daughters was Sultan Fatima (mother of Faiz) was the daughter of a landowner in the nearby village of Jessar. In 1909, Sultan Fatima gave birth to first son, Tufail Ahmed, followed three years later by second Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Two more sons, Inayat and Bashir were born too. All Sultan’s sons, except Bashir, a physically and mentally disabled child from birth, rose to prominent positions in their careers. Tufail Ahmed, a judge, Faiz, a teacher, Editor and eminent poet, Inayat, a Major in the Army. Sultan Muhammad of Kala Kader, well acquainted wit British and Afghan aristocracy easialy moved in the British aristocracy much of his pictures, preserved by his successors are witness to it. He was bestowed upon numerous decoration and honours by the British crown including the title of “Khan Bahadur”and vast tracts of land in Sargodha.

Works

Sultan Muhammad Khan’s intellectual and literary contributions include: “The Constitution and Laws of Afghanistan”, conmrising 164 pages, published in London, in 1900 by Jon Marry Printing press; Biography, The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan,in two volumes, printed in 1900, by John Murray, AlbemAree Street London, reprinted, in 1980, by Oxford University Press, Karachi. The original version vol.1 of the book contains 295 pages, Note of the publisher, preface, twelve chapters and list of illustrations. Sultan Muhammad Khan’s “The Constitution and Laws of Afghanistan” comprises an introduction ten chapters and two appendices. First chapter begins with Historical Outline and last Chapter is comments on Private Law. The professed aim of writing this book has been to compare private and constitutional laws of Afghanistan with advanced European countries. His research question has been how far laws and customs practiced in Afghanistan were based upon ancient oriental customs and Muhammadan law? Additionally, how much Afghanistan, in terms law, borrowed from India and other neighbouring countries? He also tried to distinguish contribution of Amir Abdur Rahman in this regard. He fondly refers to Wheeler, former stae Secretary that Amir Abdur Rahman was the first ruler of Afghanistan who made official work formal by constructing a Government Secretarite, in his supervision

The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman Vol.1 & Vol.2 reveals originality of Sultan Muhammad’s work. The author states that:

“…the first part of the book was written by Amir himself and I am depositing in the British Museum, oriental reading room, a copy of the original. The rest was written in my hand writing from the Amir’s dictation, during the time of my holding the office of Mir Munshi.”

However, an eminent Afghan scholar, Muhammad Hassan Kakar, in his book, Afghanistan A Study in International Political Developments 1880 – 1896, argues:

“… it is not an autobiography in its entirety, however, for only the first part, covering the events of Abd al-Rahman’s early life up to his arrival in Afghanistan, was written by the Amir himself. The manuscript is undated and preserved in the Mss[sic.--] Department of Kabul Public Library. It is not definite when the Amir wrote it, but in 1303/1886 it was published under the title of pandnama-i-dunyawa din, (a Book of Advice on the World and Religion). Sultan Mahomed has simply incorporated its English translation in the so-called Autobiography of the Amir.”

Hassan Kakar further comments on second part of the book:

“About the rest of the book, Sultan Mahomed, a Panjabi native of “humble” origin in the service of Amir Abd al-Rahman as an interpreter and secretary (munshi), claims he wrote it as dictated by the Amir himself, but this is not true. In 1895,

Mr. Gray, the Amir’s former physician sent him his book, “My Residence at the Court of the Amir” – a collection of personal impressions of rather insignificant matters.”

According to Hassan Kakar, Amir Abdur Rahman was displeased with the book and later his son and successor, Amir Habibullah Khan, expressed extreme displeasure at Sultan Muhammad. Resultantly, he was never allowed to return to Kabul, despite the fact that he was tutor of Amir Habibullah Khan. Although, some Indian governmental circles considered Sultan Muhammad was sent abroad to spy for the Amir of Afghanistan. However, others believe that Sultan Muhammad was a spy of British Indian Government rather than Amir of Afghanistan. Upon discovery that he worked for British Indian Government his own pupil Amir Habibullah Khan did not allow him to come back to Afghanistan. Sultan Muhammad Khan passed away in 1931 in Sialkot.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that Sultan Muhammad Khan worked not only to preserve and strengthen independence of and stability in Afghanistan but also assisted in modernization of and promotion of constitutional rule in Afghanistan. He tried to tightly guard Amir’s secrets despite prevalence of spies of the British and Russian government in the Afghan Court. Although, he was accused of being a spy of the British government, his services for the advancement of Afghanistan cannot be undermined. Keeping in view his political and constitutional services, literary contribution, and his work as Mir Munshi Aala (Chief Secretary) especialy, during parleys of the Amir with British Mission to demarcte Afghan borders, and the trust Amir reposed in him testifies to the fact that he remained a friend of Afghanistan. This can be also substantiated by the fact that he was arrested by and jailed in Lahore Fort by the British Indian Government where later Faiz ahmed Faiz was jailed by the successor Pakistani government who opposed British an US imperialism in 1950s. Moreover, suffice to say that not only Amir Abdur Rahman (who trusted him) appointed him as Afghan Ambassador to England for three years but his successor Habibullah Khan, reposing confidence in him, also allowed him to continue as Ambassador till 1905.

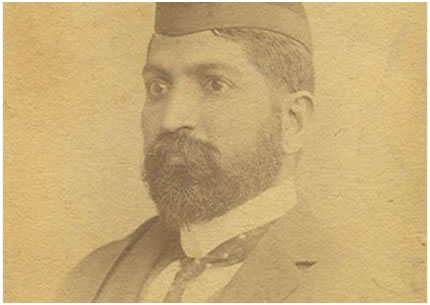

Faiz's father, Sultan Muhammad Khan

(Mir Munchi Aala in Afghanistan 1888-1898)

A painting of Dr. Lillias Hamilton, Sultan Muhammad’s friend at the Afghan court (1894-1898)

Bibliography

Ahmad, S., (2009): Kala Qadir Kaa Charwaha (Urdu). Islamabad: Quarterly Adbiyat, Academy Adbiyat Pakistan.

Centenary Celebrations of Faiz Ahmad Faiz. The Daily Dawn, Islamabad, dated 11.02.2011.

Dupree, L. (1980): Afghanistan. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Elphinstone. (1998): Account of the Kingdom of Caubul. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi.

Ghani, A., (1989): A Brief History of Afghanistan. Najaf Publishers, Lahore.

Gray, J. A., (1987): My Residence at the Court. Darf Publishers Ltd, London.

Hameed, R., (2009): Faiz Ahmad Faiz: Sawanhi Khaka. (Urdu). Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, Islamabad.

Hamilton, L., (1900): A Vazir’s Daughter. John Murray, Albemarle Street, London.

Hamilton, L., (n.d): The Power that Walks in Darknesses (Unpublished Novel). The Indian Office Record, typescript copy.

Jameel, S. M., (2013): Zikr-e- Faiz (Biography) (Urdu). Cultural Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi.

John, A. G., (1995): At the Court of Amir: A Narrative. Richard Clay & Sons, London.

Kakar, H. K. (2011): Government and Society in Afghanistan: The Reign of Amir 'abd Al-Rahman Khan (Cmes Modern Middle East Series). University of Texas Press, Texas.

Kakar, H. M., (1971): Afghanistan: A Study in International Political Developments 1980-1896, Punjab Educational Press, Lahore.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., (1900): The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-II. John Murray Albemarle Street, London.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., (1900): The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-I.. John Murray Albemarle Street, London.

Khan, M. S. M., (1900): The Constitution and Laws of Afghanistan. John Murray, London.

Latif, A., (2003): Judiciary in Afghanistan Since the Days of Amir Abdur Rahman. Peshawar (Unpublished Ph.D dissertation), submitted to Area Study Centre, University of Peshawar, Peshawar.

Lee, J., (1991): Abd al-Rahman Khan and the Maraz Ul- Muluk. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ludwing, W. A., (2008): Biographical Encyclopedia of Afghanistan. Pentagon press Delhi.

Majeed, S., (Ed.)., (2005): Culture and Identity: Selected English Writings of Faiz. Oxford University Press, Karachi.

Past, R. J., and Gacek, T., (2009): Proceedings of the Ninth Conference of the European Society for Central Asian Studies. Cambridge Scholars publishing.

Ram, S. & Bajpai., (2002): Encyclopedia of Afghanistan Vol-III, Kingship in Afghanistan. Anmol Publications,India.

Reynolds, D., (2004): Christ’s: A Cambridge College over Five Centuries . MacMillan.

Saeed, A., (1992): Islamia College Lahore ki Sad Sala Tarikh (Urdu). Azhar Sons Printers, Lahore.

Saleem, A., (2009): Kala Qadir Kaa Charwaha (Urdu). Quarterly Adbiyat, Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, Islamabad.

Sheema, M., (2006): Culture and Identity: Selected English Wirting of Faiz. Oxford University Press, New York.

Sultan, M., (1980): The Life of Abdur Rahman Amir of Afghanistan. Oxford University press, Karachi.

Vassilyeva, L. A., (2013): Pervarish Loho Qalam, Faiz Hayat aur Takhliqat’ (Nurturing Tablet and Pen, Faiz Life and Works). Oxford university press, Karachi.

Vector, K., (Tr.and Ed). (1973): Poems by Faiz. Oxford University press, Karachi.

Warburton, R., (1975): Eighteen Years in the Khyber, 1879-98. Oxford University Press, Lahore.

Wheeler, S., (1896): The Amir Abdur Rahman. Frederick Warne & Co, New York.

* Prof. Dr. Sarfraz Khan currently serves as Director, Area Study Center, University of Peshawar.

** Ph.D., Research Scholar, Area Study Center, University of Peshawar, currently Lecturer, Pakistan Studies, Islamia College University, Peshawar.

Aitchison, C. U., A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads vol. 13. Original Text of Anglo Russian Convention 1907, p 125.

Charkhi Brothers, belonging to a village,Charkh, in the administrative district of Logar Province: Ghulam Siddiq Charkhi, Ghulam Nabi Charkhi and Ghulam Jilani Charkhi were sons of Amir Abdur Rahman’s famous General Ghulam Haider. They later supported King Amanullah and were hostile to a new dynasty established by Mohammad Nadir Khan. Ghulam Nabi Charkhi was executed in 1932; and Ghulam Jilani Charkhi in 1933 by Nadir Khan. Ghulam Siddiq stayed outside Afghanistan with exiled King Amanullah (d. 1962) and buried in Afghanistan. See: Ludwing, W. A., Biographical Encyclopedia of Afghanistan. Pentagon press, Delhi 2008, pp. 65, 95-96.

Tarzis,Muhammadzai of the line of Painda Khan, born in Ghazni, Mahmud Tarzi (1865-1933), son of a literary figure Ghulam Muhammad, pen name Tarzi, exiled in 1881. Mahmud received his early education in British India and then proceeded with his father in 1885 to Baghdad, Istanbul and later to Damascus. The caliphate of Islam had lost its luster and the Tarzi family comprising more than a dozen individuals, partly receiving financial assistance from the Ottoman Court. Mahmud equipped with both formal and practical knowledge returned to serve his country in 1902.

The Musabeheen Yahyakhel, descendants of Sultan Muhammad Khan, who ruled Peshawar as governor for the Sikhs. One of Sultan Muhammad’s sons, Yahya Khan, had followed Yakub into exile in India after the death of Cavagnari and the renewed British invasion in 1879. His son Muhammad Yousaf Khan had five children who played an important part in the development of modern Afghanistan. The five-Muhammad Aziz, Nadir Khan, Hashim Khan, Shah Wali and Mahmud were all educated in India and returned to Afghanistan, in 1901.

Abdur Rahman ascended the throne of Afghanistan with the British support, surrendered to them control of his foreign affairs, in lieu, of an annual subsidy of ₤80 thousand.

Ram, S. & Bajpai., Encyclopedia of Afghanistan Vol-III, Kingship in Afghanistan. Anmol Publications,India 2002, p 13.

Sheema, M., Culture and Identity Selected English Writings of Faiz. Oxford University Press, Karachi 2006, p 5.

Vassilyeva, L. A., Pervarish Loho Qalam, Faiz Hayat aur Takhliqat’ (Nurturing Tablet and Pen, Faiz Life and Works). Oxford university press, Karachi 2013, pp. 2-4.

Saleem, A., Kala Qadir Kaa Charwaha (Urdu). Quarterly Adbiyat, Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, Islamabad 2009, p 303.

The name of Sultan Muhammad Khan’s grandfather was Sir Buland Khan and the name of his father was Sahib Zada Khan.

Hameed, R., Faiz Ahmad Faiz: Sawani Khaka.(Urdu). Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, Islamabad, 2009, p. 306.

Sheema, M., Culture and Identity: Selected English Wirting of Faiz. Oxford University Press, New York 2006, p 19.

Sheema, M., Culture and Identity: Selected English Wirting of Faiz. Oxford University Press, New York 2006, p 29.

Sheema, M., Culture and Identity: Selected English Wirting of Faiz. Oxford University Press, New York 2006, p 26.

Jamil, S. M., Zikr-e- Faiz (Biography) (Urdu). Cultural Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi 2013, p 46.

Saeed, A., Islamia College Lahore ki Sad Sala Tarikh (Urdu). Azhar Sons Printers, Lahore 1992, pp 18-20.

Sheema, M., Culture and Identity Selected Eglish Writings of Faiz (Urdu). Oxford University Press, Karachi 2006, p 18.

Lee, J., Abd al-Rahman Khan and the Maraz Ul- Muluk. Cambridge University Press, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 1991, p 209.

Kakar, H. K., Government and Society in Afghanistan: The Reign of Amir 'Abd Al-Rahman Khan (Cmes Modern Middle East Series). University of Texas Press, New York 2011, p 68.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-I. John Murray Albemarle Street, London 1900, p 270.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-I.. John Murray Albemarle Street, London 1900, p 146.

Khan, M. S., The Constitution and Laws of Afghanistan. John Murray Albemarle Street, London 1900, p 45.

Hamilton, L., The Power that Walks in Darknesses (Unpublished Novel). The Indian Office Record, typescript copy.

Dr. Lillias Anna Hamilton M.D., (7th February 1858 – 6 January 1925) was English pioneer female doctor and author. She was born at Tomabil Station, New South Wales to Mr. Hugh Hamilton (1822 – 1900) and his wife Margaret Clunes (nee Innes). After attending school in Ayr and then Cheltenham Ladies’ College, she was trained first as a nurse, in Liverpool, before going to study medicine in Scotland, qualifying as a Doctor of Medicine in 1890. She was a court physician to Amir Abdur Rahman Khan in Afghanistan in the 1890s, and wrote a fictionalized account of her experiences in A Vizier’s Daughter: A tale of the Hazara War,published in 1900. After a spell in private practice in London, she became Warden of Studley Horticultural College in the years before World War 1, leaving the College in 1915 to serve in a typhoid hospital in Montenegro under the auspices of the Wounded Allies Relief Committee. Her other published works include A Nurse’s Bequest, 1907. Similarly, she had typed a novel which could not be published still lying in the India office record, “The Power that Walks in Darknesses”.

In 1894, Dr. Lillias Hamilton arrived in Kabul from India. Before her arrival in Afghanistan, Dr. John Alfrad Gray was the court Physicain of Amir AbdurRehman (1888-1894). Hamilton arrieved in Kabul on 25th April 1894, Hamilton’s arrival in Kabul seems mysterious it was rumoured that Gray was suspected by Amir as British Agent. In her private letters she states despite poorrhealth,she proceeded to replace court physician, the costs of her road expenses were covered by the Indian government. Her former headmistress at Cheltenham Ladies' College, wrote to Hamilton: "We think you have received a special call from God to prolong, perhaps save, the life of the Ameer", Principal, Cheltenham Ladies' College to Dr. Hamilton, Oct. 1894, WHIML:PP/HAM/Ai. 70 Trans-Frontier Journal, June 1894, IOLR:SLEI/L/PS/7/75 fol. 109. 71 KN, 9-12 June 1894, IOLR:SLEI/L/PS/7/75 fol- 131 72

Unpublished record in the India Office Library and Records, such as the diaries of the various native news writers in Kabul, Qandahar, Heart etc., the confidential reports of British agents, diplomats and travelers, and translations of letters, proclamations and tracts by Abdul Rahman Khan himself, also provide considerable detail about the Amir’s mental and physically health.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-II. John Murray Albemarle Street, London 1900, p 273.

Kakar, H. M., Afghanistan: A Study in International Political Developments 1980-1896, Punjab Educational Press, Lahore 1971, p 147

The name of his wife was Sayra Jan, she was the daughter of Sardar Muhammad Rafiq Khan, the brother of Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, unfortunately, within two years, she died and buried in place namely Budkhak situated four miles away from Kabul city. She had given birth to a girl Bibi Gul. Later on at the age of eighteen Bibi Gul came to Jehlam and on ward to Sialkot. She had looked after Faiz Ahmad Faiz. Bibi Gul died in Abbotabad at the age of 50. See Jameel, S. M., Zikr-e-Faiz (Urdu). Cultural Department, Government of Sindh, Karachi 2013, p 31.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-II. Oxford University Press, Karachi1980, p 160.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-II. Oxford University Press, Karachi1980, p 161.

Lee, J., Abd al-Rahman Khan and the Maraz Ul- Muluk. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, p 176 .

Sir Thomas Salter Pyne, 1860 – 1921) was a British engineer based in Afghanistan. He was born in Shropshire and apprenticed to an engineer at the age of 15, becoming manager of a foundry and engineering works by 1879. In 1883 went out to India, where he worked for the merchant Thomas Martin for a few years. In 1887, when Martin was appointed Agent byAbdur Rahman Khan, the Amir of Afghanistan, he was sent by Martin to Kabul to be Chief Engineer of Afghanistan. There, as the first European to live in Afghanistan since the Second Anglo-Afghan War of 1879–81, he trained the local people to make guns, swords, ammunition, coins, soap, candles, etc. On behalf of Martin's firm, he built an arsenal, a mint and various factories and workshops, employing in total some 4000 workers. In 1893 he was sent to India by the Amir as a Special Ambassador, and at the conclusion of the negotiations was invested a Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI) and knighted by the British government in recognition of his services. He was also a vital contact with the Durand Mission who were defining the borders of Afghanistan. He left the Amir's service in 1899 because of failing health and was replaced by Thomas Martin's younger brother Frank. He died in 1921.

Lee, J., Abd al-Rahman Khan and the Maraz Ul- Muluk. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, p 178.

Khan, M. S. (Ed.)., The Life of Amir Abdur Rahman, Vol-I. Oxford University Press, Karachi1980, p 28.

Hameed, R., Faiz Ahmad Faiz: Sawani Khaka.(Urdu) . Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, Islamabad, 2009, p 306.

Kakar, H., K. Government and Society in Afghanistan: The Reign of Amir 'Abd Al-Rahman Khan (Cmes Modern Middle East Series). University of Texas Press, New York 2011, p 38.

Khan, M. S., The Constitution and Laws of Afghanistan. John Murray Albemarle Street, London 1900, p 46.

Majeed, S. (Ed.)., Culture and Identity: Selected English Writings of Faiz. Oxford University Press, Karachi 2005, p 7.

Cunningham to Lee Warner, India Office, 14 Sept. 1897, IOLR : SLEI/L/PS/7/95 no. 959, the annual indexes of the Political and Secret Department.

Lee, J., Abd al-Rahman Khan and the Maraz Ul- Muluk. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1991, p 177.

Munshi Chiragh Din founder of the Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam Punjab, Lahore and his colleagues established it in 1884.The founding members of the Anjuman Himayat-e- Islam Punjab Lahore, besides, Munshi Chiragh Din, included Khalifa Hameedud Din, Maulana Ghulam Ullah Qasoori and Pir Shams-ud-Din. Kahlifa Hameed-ud-Din, Maulana Ghulamullah Qasoori became the first President and General Secretary respectively of the Anjuman.The aims and objectives of the Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam included: To counter the anti-Muslim propaganda of the Christian Missionaries; To establish Islamic educational institutions and Islamic social welfare for orphans; Launching monthly, later Weekly, Magazine, titled, Himayat-e-Islam. In 1884 to 1972, the Anjuman established five colleges including, Islamia College Lahore, Amir Habibullah Khan of Afghanistan, in 1907, inaugurated its new building.

Prince Nasrullah Khan, second son of Amir Abdur Rahman was born in 1874 in Samarqand during exile of his father in Russian occupied Turkistan. In 1880, his father reoccupied his throne, his elder brother Habibullah became the Prince. Nasrullah,not well versed in English,at the age of twenty, had the opportunity to meet the Queen Victoria during his visit to England in 1895. He met the Queen in Windsor while visiting Railway of Liverpool overhead. He had the opportunity to go to Paris, Rome and Naples and came back to Karachi on 16th October, 1895. He went to Kabul via Quetta, Chaman and Kandahar.

Saeed, A., Islamia college Lahore Ki Sad Saala Tareekh.(Urdu). Lahore:Azhar sons printers,1992, p 26.

Christ’s College was first established as God’s House in 1437 by William Byngham, a London Parish priest, for training grammar school masters. In 1505, with a royal charter from the King, the college was re-founded as Christ’s College. Lady Margaret Beaufort has been honored ever since as the Founders. Christ’s was noted for several eminent scholars who sought to harmonise traditional Christian faith with the new truths of natural science. These included Cambridge Platonists such as Ralph Cudworth , and William Paley, whose Evidences of Christianity (1794) remained set reading in Cambridge until the 20th century.

Quarterly Adbiyat, No 82. Islamabad: editor in Chief Fakhr-ul-Zaman, Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, 2009, p 306.

Saeed, A., Islamia College Lahore ki Sad Saala Tareekh 1892-1992. Azhar Sons Printers, Lahore 1992, p 39.

Sir Abdul Qadar (1874-1951) was an eminent lawyer, journalist and critic born in Lodyana. He was appointed as the editor of the first English newspaper “Observer” in 1895. He went to England for higher studies and returned to India in 1906 after completing his Bar at Law. He served in different influential capacities throughout his life. He served as Judge of High court (1921), President of Punjab Assembly (1922), minister of Education(1925), Participated in League of Nation conference in Geneva (1926), Member of Punjab Executive Council (1928), High Court Judge (1930), Member of viceroy Executive Council (1939) and Chief Justice of Bahawalpur High Court (1942) Sir Abdul Qadar was a lover of Urdu language. He started a literary journal of Urdu named “Mekhzan” having contribution of top literally critics and poets. He was a close friend of Allama Muhammad Iqbal and wrote preface of “Bang-e- Dara”, remained the president of Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam Punjab and wrote two travelogues”Darbar-e-khilafat” about Turk Caliphate and “Safar nama-e-Europe”.

Sultan Fatima was the fifth wife of Sultan Muhammad Khan, in 1908 gave birth to her first son Chaudhry Tufail Ahmad, M.Sc. Physics from Aligarh, later on a Judge, three years later, 1911, the second son Chaudhry Faiz Ahmad was born, the third son had been Chaudhry Inayat Ahmed, a Barrister, later he joined Army as Major and the last son Chaudhry Bashir Ahmad was physically and mentally disabled.

Ahmad, S., Kala Qadir Kaa Charwaha (Urdu). Islamabad: Quarterly Adbiyat, Academy Adbiyat Pakistan, 2009, p 310.

Sultan, M., The life of Abdur Rahman Amir of Afghanistan. Oxford University press, Karachi 1980, p 06

Kakar, M. H., Afghanistan: A Study in International Political Developments 1880-1896. Punjab Educational Press, Lahore 1971, p 219.