Defense and Security Ties

The US-Kazakhstani security ties including in “non-proliferation has been a cornerstone of the relationship” says the US State Department, which again stressed that “Kazakhstan showed leadership when it renounced nuclear weapons in 1993” (DOS-BN 2009). In this area the US has helped Kazakhstan, under treaties signed on 13th December 1993 and multi-lateral ones committed to even earlier (DOS 1992, pp. 1-2), as noted below, to remove nuclear warheads, weapons-grade materials , and their supporting infrastructure. The US under the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program spent U.S. $ 240 million in assisting Kazakhstan eliminate WMD and their related infrastructure (DOS-USRWK 2012). As many as 1,410 nuclear warheads were removed from their weapons, including from about 104 SS-18 ICBMs (many of which were targeted at the U.S.) and either converted or sold (EKUSA 2010). Perhaps in anticipation of this the US Department of Defense signed a “Memorandum of Mutual Understanding and Cooperation in the field of Defense and Military Relations” with the Kazakh Ministry of Defense on February 14th, 1994. Later building upon the successes of their post-Sept. 11 security co-operation, the same parties consolidated their ties in this field further by signing the “Memorandum of Consent on Mutual Intent to Implement the Five-Year Military Cooperation Plan 2008-2012” on 1st February 2008. As the website of the Kazakh Embassy in the U.S. states: “(these) plans cover the area of strengthening the fighting and peacekeeping capacities of Kazbat, airmobile forces, naval forces, as well as the development of military infrastructure in the Caspian region” (EKUSA 2013). This memorandum continues and improves upon the security cooperation tradition established under the September 2003 five year military cooperation accord.

Kazakhstan’s armed forces participate not just in the American IMET, FMF and CT bilateral assistance programs but it also joins-in, multi-laterally, in NATO’s Partnership for Peace program. The US Central Command conducts numerous bilateral events of military cooperation with the Kazakh Defense Ministry and its other agencies. These events range from mere information exchanges to full military exercises. Quantitatively, these events are rising in numbers, continually over the years. As a non-NATO member Kazakhstan was yet further accommodated within Western security structures under NATO’s Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP), Operational Capabilities Concept (OCC) and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC). As mentioned before, in a multi-lateral context Kazakhstan has already signed on and stands committed to a number of long pre-existing security-related agreements, that have a strategic dimension, even from earlier on, including the START Treaty and Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty both of 1992, the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1993 and the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 2001(DOS-BN 2009; DOS-USRWK 2012). The on-going periodic launches of a range of pyrotechnics from the Baykonur Cosmodrome, near the Kazakh town of Tyuratam, should be seen in this context. Both Kazakhstan and the U.S. are concerned, nonetheless, but for mostly different reasons.

American BDA in the Strategic Realm - American aid to Kazakhstan, as mentioned elsewhere, is not all confined to politico-legal, socio-economic and developmental sectors alone. An important policy area of developmental assistance is the defense and security sector. Principally, the U.S. urged and supports Kazakhstan’s adherence to all previous arms control agreements and treaties. Kazakhstan has benefited from various security-related assistances too. In the realm of defense, almost from the beginning, the U.S. had been involved in defense reform in Kazakhstan. The U.S. Department of Defense launched the CTR program in 1992 to facilitate the dismantlement of weapons of mass destruction across the former Soviet Union, including within Kazakhstan (Dec. 1993). It has helped in the conversion and management of at least four nuclear facilities. Being successful over the years, this program has been continuing also since its renewal in 2006. In this context, an amendment to the Nunn-Lugar program was signed on 13 December 2007, prolonging the same till 2014 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MFARK) 2008). This program promoted denuclearization and demilitarization. Specifically, Kazakhstan has co-operated with, ironically, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) on matters such as nuclear materials safeguards and non-proliferation issues. With U.S. assistance, Kazakhstan closed 221 nuclear test tunnels at the Semipalatinsk Test Site (STS) by Nov.2012 (DOS-USRWK 2012). The world’s only nuclear desalinization fast breeder reactor at Aktau had about 300 metric tons of enriched uranium and plutonium spent fuel, in storage pools, to be properly secured (Nichol 2013a, p.63). The U.S. government’s involvement in the handling, variously, of this radioactive material, of reactor BN-350 in the Mangyshlak Atomic Energy Complex at Aktau, has continued beyond 2010 to the present.

Kazakhstan has since 1994 been having an active partnership with the Arizona National Guards, including by co-exercising in the recent Steppe Eagle 2016. Particularly, but not exclusively, after the terroristic attacks of September 11, 2001 Kazakhstan had offered the U.S., intelligence sharing, opening of air corridors and even allowed the use of its airfields. Confidential sources say that a number of bases in eastern Kazakhstan were considered for this purpose. Specifically, the Kazakh defense ministry says the U.S. government requested the use of military bases at Taraz and Taldykorgan. The U.S. is involved in the reform of the Kazakh armed forces. The U.S. helped Kazakhstan’s Defense Ministry in areas of military reform including in creating an adequate Kazakh force structure. The U.S. helps increase the professionalism of the Kazakhstani military, by providing the required training and equipment, so that they can better protect their sovereignty and territorial integrity. Remarkably, Kazakhstan has the only Humvee center in Central Asia. To strengthen Kazakhstan’s Caspian shore defenses the U.S. had provided “$20 million for radar and intercept boats” (Legvold 2004, p. 3). Joint exercises also aim to improve inter-operability of Kazakhstani forces with the U.S. military. The capacities of the Kazakh forces to participate in counter-terrorism and peacekeeping operations abroad, as per NATO Partnership, United Nations and Coalition goals, were enhanced (DOS-FOA 2013).

In this regard, Kazakh military personnel, including 27 (49 according to wikipaedia) combat engineers and sappers, participated in coalition operations in Iraq in 2003, under OIF (2003-2008), and helped clear about 1.5 million mines per year there. Under the Partnership for Peace (Pfp) Trust Fund, Kazakhstan destroyed numerous conventional landmines/explosives, within its own territory and did similar activities in Iraq too. In fact, it destroyed about 4 million mines there, asserted the Kazakh Embassy (EKUSA 2013). Their experience there prepared them for later peacekeeping duties with both the United Nations and NATO. Kazbat (created in Jan. 2000) has involved itself, remarkably, in peacekeeping duties, under UN mandate, in Iraq. It had thus, multi-laterally, been “incorporated in UN Blue Helmets” and NATO inter-operability, a U.S. objective, was also gained by Kazakhstan, thereby (Centre of Foreign Policy and Analysis 2003, p.20). Even presently, Kazakhstan enjoys the best level of bilateral military and technical cooperation with the U.S., amongst all the CIS states. Russia’s legitimate concerns on NATO affairs, involving the FSU, had been moderated to an extent, through the creation of the NATO-Russia Council, which allows Russia some inter-face ability, without giving it veto power over any NATO moves. It is under this background, of lukewarm but tacit approval, that NATO, with strong U.S. backing, helped and helps restructure even the Kazakh military, as hinted to earlier. In this context, Kazbat which, actually evolved from the earlier CENTRASBAT had been transitioning to KAZBRIG at least since 2008, if not earlier. It would be an added peacekeeping asset to the lean 32 brigades-full Kazakhstan Army.

The U.S. Central Command organized various cooperative security-related events in Kazakhstan, in its AOR and elsewhere too. It also co-operates bilaterally and participates in bilateral military exercises. Kazakhstan and the United States have hosted joint exercises, including series named such as Balance, Cooperative Nugget, Combined Endeavor, Zhardem, and Regional Cooperation Exercises. The annual series called Steppe Eagle began in July 2003. Steppe Eagle 2011 was held from August 9-19, 2011 at the IIiy (Ilysk) range, focusing on peace-keeping interoperability. The two week long Steppe Eagle 2013 started on 10 Aug. and the drill involved assessing the operational capability of the long restructuring KAZBAT. With the KAZBRIG alas represented, at stage 2 of the Steppe Eagle 2016 held at Stanford, U.K., by at least 270 personnel, the series has quite successfully continued to the present times. In direct military to military cooperation, Kazakhstan participated and still participates in the American IMET and FMF programs. Kazakh military officers attend the George C. Marshall Centre programs. Security assistance includes English-language and military professionalism training, via IMET program. The U.S. seems to believe that military exchanges, visits and various other forms of engagements, with the Kazakhs, would be useful tools in exposing the Kazakhs to the military practices and values of the U.S. and in building goodwill and credibility, generally.

When it comes specifically to security, the U.S. helps the Government of Kazakhstan (GOK) to draft effective legislation and improve enforcement of existing laws, by providing relevant training to customs and other enforcement officials, to tackle all manner of trafficking in of narcotics, persons and WMDs. It has helped procure detection equipment for border guards. In the area of security assistance, the U.S. helps Kazakhstan by providing training and equipment to combat transnational threats such as WMD technology and materiel proliferation, increase border security, counter-terrorism co-operation, especially after the advent of the so-called “war on terror”, and to address other seemingly “lesser” security related threats such as money laundering, terrorism financing, illegal drugs and trafficking in persons, illegally. “Specifically, the United States is supporting the GOK’s plans to build a WMD interdiction training facility, and providing regional enforcement training for Kazakhstan and its neighbors” (DOS-FOA 2013).

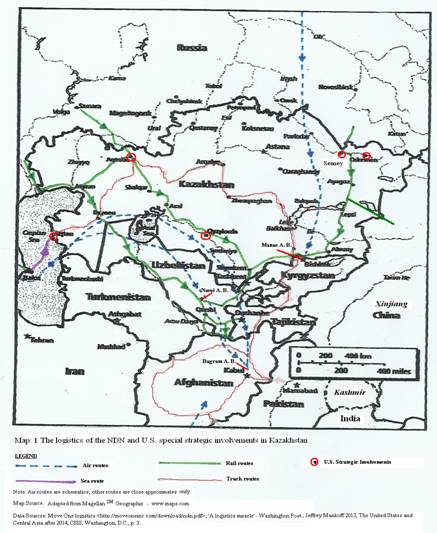

The U.S. supports the anti-terrorism Rapid reaction force and had helped in the refurbishment of security helicopters. Despite the broad range of its defense and security cooperation with the U.S., Kazakhstan has avoided having any U.S. bases on its territory and had since July 2005 demanded the U.S., interestingly, via the SCO to set a timetable to quit even its existing bases elsewhere in Central Asia (NCAFP 2007, p. 6; Kukeyeva and Baizakova 2009, p.41). Simultaneously, however, in the context of the United States’ impending so-called “exit” from Afghanistan, Kazakhstan has earnestly extended its co-operation and support to the NDN, an American-led logistics arrangement (as we saw earlier in Map 1), at uneconomically higher costs, that was intended to reduce supplies transiting Pakistan, by relying more on, the apparently more reliable, routes and ports of northern Eurasia. In this regard, Kazakhstan advocated the increased use of Aktau, presumably for containers, that then brought in U.S. $17,500 in transit fees each, and which transshipped via Poti (Mankoff 2013).

Conclusions

Eyeing the obese soft underbelly of the Soviet Union, including the affairs of Soviet Kazakhstan, was a favorite American Cold War pastime. Yet a liposuctioned off independent Kazakhstan received, at best, a lukewarm reception from the United States in comparison to the NIS of the Baltic, Caucasia and even, Kazakhstan’s step-mother, Russia itself, upon its independence. Despite the, paradoxically, euphoric slow start, over the past two decades and a half, U.S. - Kazakhstan relation shows a gradual upward trend, tri-lineally in strategic, economic and political terms, exactly in that order of relational strength. Remarkably, even the tragic September 11th episode had a positive impact on these relations too.

Despite that initial euphoria at Kazakhstan’s independence and the early geo-strategic imperatives to be addressed, via the establishment of diplomatic and security relations with it, generally, relations between Kazakhstan and the United States only proceeded incrementally, between the years 1995 to 1999 and this pattern continued somewhat similarly thereafter between 2000 to 2003 but with a change of focus in policy, aimed later more on counter-terrorism. In this context, Central Asia, generally, and Kazakhstan particularly was already poised to gain positively, when the monstrously tragic Sept. 11, 2001 terroristic attacks took place, on iconic and strategic buildings in key U.S. cities. Sure enough, the U.S., instantly, realized the strategic importance of the Central Asian region to its national security, as a result. Accordingly, President Bush reoriented America’s attention back to the Central Asian region from Clinton’s, well-advised but rather premature, indulgence with India.

In these periods too, two general trends were discernible in Kazakhstan-U.S. interactions. Firstly, after the deflation of its initial high expectations in its relations with the U.S., Kazakhstan had been, understandably, quick to reinvigorate its lessening ties to Russia. This, in turn, served to dampen somewhat American keenness to deepen its relations with Kazakhstan. Second, as energy, particularly oil including its equities, facilities and discoveries expand and became available for foreign participation (as we saw in the section on Energy Dealings) in Kazakhstan and its environs, the U.S., as pushed by its well-entrenched oil lobby, began to appreciate even more, the need to develop greater ties with Kazakhstan (Legvold 2004, pp.1-2). Nevertheless, a number of issues did and do bug the relations between these two countries. These included the U.S. occupation of Iraq, uncertainty about American’s real agenda for the Af-Pak hyphenation, American lukewarmity towards the Muslim Central Asian region, generally, and America’s attitude towards Islam and Muslims and, particularly so, the Western bracketing of terrorism with Muslims (Nazarbayev 2003, p. 29).

Over the recent decades and varyingly through the various administrations, the U.S. has broadly kept to its strategic objectives in Kazakhstan. As the lone superpower desperately clutching to its fleeting unipolar moment, it has used the same to pursue its security, political, economic and strategic interests, as elsewhere, in Kazakhstan too. Similarly, Kazakhstan in keeping with the foreign policy dictum of its, then de facto, Father of the Nation has pursued the same by seeking to meet its economic, security, political and developmental needs, through its relations with the U.S., which, by the way, occupies the fifth circle in Kazakhstan’s favorite foreign policy model. Both these countries were, and still are, trying to compensate somewhat for the diminishing opportunities and rising challenges in their traditional domains, by gradually seizing the new and rising opportunities in different sectors, presented by each to the other. Kazakhstan sees in the U.S., a hedge against a potentially imperialist, reverting Russia and, the U.S., in turn, sees Kazakhstan as a key Eurasian foreground to transplant, if haltingly, sustainable freedoms in and around Eurasia. In thus pursuing their strategic intercourse, Kazakhstan sought to refrain from relapsing into international isolation and the U.S. seeks thereby, to refrain from courting Eurasian irrelevance.

On the political front, unlike Russia and China who found the status quo advantages, the U.S. has been, rightly and responsibly, concerned about the halting democratic development in Kazakhstan. It has long viewed corruption, clientelism, weak pluralism, lack of freedom of association and other human rights abuses with legitimate concern. As noted herein earlier and also as generally reflected in the larger literature, Americans have regularly raised these issues and America’s developmental assistances, in the politico-legal and socio-environmental sectors, have largely been addressed to pursue these issues. While Kazakhstan’s 1991, 1999, 2005, 2011 and subsequent presidential election records may not all measure up to European standards, the U.S. is right to acknowledge the democratic improvements, however haltingly, that has taken place over successive elections, including in the legislative ones, in Kazakhstan (EKUSA 2012). However, outside observers, including clear third parties, too are right in feeling that America’s energy interests do override its, seeming, democratic concerns in Kazakhstan and that there is still much more to be desired, in this regard (Kessler 2006; Yazdani 2007).

Given how the year 2000 U.S. elections actually undermined American democracy, Kazakh leaders may be forgiven for looking up instead to Yeltsin’s manner of nominating his successor, as a more practical, if not also worthy, model to emulate, in their own succession exercise when it inevitably arrives in the future, at least they would then not have to judicially short-circuit genuine democracy, which they, despite being recent democratic converts, truly value, when doing so. As we saw elsewhere, given America’s certainly deeper democratic traditions, the U.S. was able to pursue its relationship institutionally, that despite changes in and of U.S. administrations and even internal turf wars, the U.S. did manage to continually build-up its ties with Kazakhstan. Whereas Kazakhstan, on the contrary, being new to the Western democratic philosophy, badly needed the comforting tutelage of its pioneering Leader (or its de jure Father since June 2010), not only to stabilize and strengthen its statehood, including by invoking the Astana Spirit, but also to anchor, smoothen and hopefully, secure its American relationship, at least in these formative decades. Therefore, in the interest of the emergence of a, genuinely, democratic future Kazakhstan, the U.S. must allow the Kazakh “El Basy” to run his, well- anointed and now legislatively-safeguarded, lifetime course fully, as per the apparent wishes of his peoples and the U.S. should just soberly jog along to reap the lasting benefits of a consequent stronger relationship. Recklessly, doing otherwise, even simply to please an immature opposition pack, would, I think, only be like unsaddling a George Washington in full gallop, and that too at mid-stream!

In the economic sphere, despite being an economic power, the U.S. lack of any direct border or boundary with Kazakhstan, truly showed its effect. While we saw their bilateral trade and other economic ties continually growing, these have not been as impressive as Kazakhstan’s economic ties with either China or Russia, both of which amicably share borders with Kazakhstan and enjoy the consequent economic boon, thereby. As we saw too, the U.S. had invested rather heavily in the Kazakh energy sector, being acutely aware of the economic vulnerabilities of rent-seeking economies like Kazakhstan to the Dutch-disease, the U.S. was right in launching the Houston Initiative to nurture entrepreneurship and take Kazakhstan on the, hopefully sustainable, path to economic diversification, that may bring in greater socio-economic spin-offs. In these contexts and more, as we have seen, the U.S. had offered much technical assistance. Despite the challenges in the region, the U.S. – Kazakhstan relationship has been quite significant in strategic, investment, business presence, development assistance and trade terms. To be sure, the U.S. business presence in Kazakhstan has had a relatively positive import on the Kazakhstan economy. The increase in investments, except in the oil sub-sector perhaps, and business involvement of U.S. corporations and their joint–ventures have, inevitably, boosted demand for the U.S. dollars and this would depreciate the Kazakhstan tenge and tiyn, thereby hopefully, creating spin-offs for the Kazakh economy.

Being from a society that had willy-nilly became heterogeneous over time, Kazakh leaders have been keen to interact and gain insights from other similar societies, where immigrants have overwhelmed the natives in most, if not in every sphere, often resulting in latent native bitterness. In this regard, not just mighty indifferent America but even affected Asian “Tigers” such as Singapore and Malaysia served and serve as case studies from which Kazakhstan can, did and do learn on how this disturbing phenomenon was and is variously managed and the bitterness tactfully addressed, sometimes still to the natives’ continuing silent dissatisfaction. Hopefully, the Kazakh leaders would draw the right lessons, also from the bottoms of these afflicted societies, so as not to repeat the follies, arising usually at their insulated tops.

Given that the U.S. sought and seeks energy security through energy diversification, its strategic reach and deep involvement in the Kazakhstan energy sector, is totally understandable. Besides turning in tidy profits, especially for the U.S. and Kazakh private sectors, perhaps even indirectly via the Bahamas, Cayman Islands, Bermuda and their likes, this involvement helps Kazakhstan gradually reduce its dependence on Russia for its oil trade and thereby provided Kazakhstan with viable alternatives and also boosted its politico-economic leverage. However, the U.S. can better serve these objectives if it also enables Kazakhstan to export its hydrocarbons also via, their competitor, Iran to the world markets. Doing so may also encourage Iran to gradually tread a less hostile nuclear path and work with the U.S. towards bringing positive regional development. Furthermore, it is also easier, in this regard, for the U.S. to prevail on Russia to withhold nuclear weapons technology from states with questionable intentions, especially given their mutual allergy for, if nothing else, “Islamic” extremism. The oily (pun intended) involvements and technical assistances the U.S. gives Kazakhstan in the energy sector should similarly also advance reforms that would, in the future, prevent any recurrences of Zhanaozen-type of violence, given that that incident arose in an energy production-linked region (see details in Nichol 2013b, pp. 4-5).

In alluding to the occurrence of violence and its consequent sense of insecurity in parts of Kazakhstan, one can easily appreciate America’s increasing involvement in Kazakhstan’s defense and security spheres. Their involvement in the denuclearization issue has been appreciated even by the Kazakhstanis themselves, unlike in Ukraine where some bitterly view their case as tripartite nailing. Anyway, the U.S. has also been involved in Kazakhstan’s force restructuring and is providing security related assistances, as we have noted earlier. Some words of caution need to be added in these regards, though. As the U.S. drawsdown from Afghanistan also via Kazakhstan, it should be careful that the consequent financial windfall, not to mention too the deadly defense items via the EDA, it leaves behind enroute and the lethal trainings it imparted and imparts to the various Kazakhstani Special Forces, are all never abused and expanded upon innocent ordinary Kazakhs who may only be attempting to recover the basic socio-economic privileges that they have recently lost through the Soviet collapse, and similarly ensure that the religio-cultural rights that the Kazakhs have regained, thereby only recently, are not beastly trampled upon, therewith.

Both the U.S. and Kazakhstan have worked hard towards integrating Kazakhstan with the world economy. While these efforts are indeed laudable, the U.S., in particular, must cobble up the necessary facilitating arrangements regionally, and in the outer Central Asian region too, to ease the integration process, so that both the U.S. and Kazakhstan can derive the maximum benefit from their economic intercourse. Their ongoing mutual involvement in Afghan affairs, in these contexts, must be welcomed too. Being remote, land–locked and lacking direct borders with the United States, Kazakhstan’s sovereignty, independence and strategic survival could not be easily safe-guarded and promoted, without taking a regional approach in the pursuance and exercise of its emergent integration with the, larger, free world. With this in mind, Kazakhstan and the United States have consistently adopted a regional approach, if not also, as yet, within a viable regional framework, and worked for gradual regional integration in all respects, save the political.

Nevertheless, in a regional context, it was Uzbekistan that enjoyed primacy of American attention during these periods and preeminently so in the years following Sept. 11, 2001 (Legvold 2004, p.1). Despite Kazakhstan having more real estate and greater economic dynamics, it was and is Uzbekistan that boasts of a higher population in the region; it is again Uzbekistan that has centrality within a reconfiguring Central Asia, i.e. it borders most of the countries constituting the region, as academically defined, and Uzbeks are found, in significant numbers, across it; and it is Uzbekistan yet again that, by virtue of its centrality and its logistical connectivity, was more relevant in America’s earlier penetrative campaigns and subsequent on-going missions in an instability-ridden Afghanistan. In these contexts, while Kazakhstan was doubtless of greater strategic importance, Uzbekistan has a higher immediate critical value and is, in fact, the logistical key to dynamically lock the region together as a coherent whole for ensuring future regional development, which in itself is a crucial U.S. objective (‘Hanging separately’ 2003).

Politically, as we have seen, the region had and has a number of burning issues, especially pertaining to natural resources, to mutual tensions and rivalries, which all need to be benignly tackled, before any dream in this regard can be brought to fruition. When and if that happens, Kazakhstan, the region and even the facilitating U.S. may begin cutting much more ice globally, so to speak. Meanwhile, generally, multi-track dialog must be strengthened and regionally-minded, multi-faceted intercourses and exchanges, at every level, must be further deepened. As a parting shot, if I were to take the professed strategic objectives of the U.S. in Kazakhstan, as quoted earlier, seriously and tally America’s actual relational record, thus far, with Kazakhstan, in its doubtless lofty light, then I must conclude, as per my present scrutiny, that the U.S. had reasonably addressed those objectives, may be not as much as it ought to have, but still it had, as we saw nonetheless, taken the right steps, it had indeed walked the talk and is in step in the steppe, up to a point!

References

Aitken, J., [2009]: Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan. Continuum, London and New York.

________ [2012]: Kazakhstan: Surprises and Stereotypes after 20 Years of Independence, Continuum, London and New York.

American Chamber of Commerce in Kazakhstan. [2016]: online at <www. amcham.kz> .

Balaban, E., [20 Nov. 2012]: ‘Arizona National Guard shares knowledge with Kazakhstan unit,’ National Guard News. Retrieved from http://www.nationalguard.mil/News/ArticleView/tabid/5563/Article, accessed on 3/02/ 2014

B.P. Global. [2013]: Statistical Review of World Energy (BPSRWE). B.P. p.l.c., London.

________ [2016]: B.P. Statistical Review of World Energy (BPSRWE) 2016, 65th edition, , B.P. p.l.c., London.

Centre of Foreign Policy and Analysis. [2003]: Kazakhstan the Crown Jewel of Central Asia, Press Service of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Kazinvest Adviser and Kazakhstanika, Kazakhstan.

Cummings, S.N., [2012]: Understanding Central Asia: Politics and contested transformations, Routledge, London and New York.

Daly, J.C.K., [2015]: ‘Central Asia Will Miss the Northern Distribution Network. Silk Road Reporters, 19 June 2015. Retrieved from http://www.silkroadreporters. com, accessed on 3 March 2017.

Dave, B., [2007]: Kazakhstan: Ethnicity, language and power. Central Asian Studies Series 8, Routledge, London & New York.

EKUSA (Embassy of Kazakhstan in the USA). [2016]: ‘Infographics,’ 2016, Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from <http:// kazakhembus.com/>, accessed on 6 March 2017.

_______ [2012]: ‘Kazakh Foreign Minister Yerzhan Kazykhanov’s Visit Further Strengthens Bilateral Dialogue,’ Feb. 2012, Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://kazakhembus.com/article/kazakh-foreign-minister-yerzhan-kazykhanovs-visit, accessed on 3 Feb. 2014.

_______ [2013]: ‘Kazakhstan-US Relations,’ Aug. 2013, Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://kazakhembus.com/Kazakhstan-US Relations, accessed on 3 Feb. 2014.

_______ [2010]: ‘President Nazarbayev Visits the United States April 12-13, 2010 for the Nuclear Security Summit,’ April 2010, Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://kazakhembus.com/article/president-nazarbayev-visits-the-united-states, accessed on 3 Feb. 2014.

Graeber, D.J., [2016]: ‘Commercial Production Started at Giant Kashagan Oil Field,’ UPI, 21 November 2016.

Hanging separately. [26 July 2003]: A Special Report, Economist. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/node/1921970, accessed online on 3 Feb. 2014.

Kasenov, O., [1995]: The Institutions and Conduct of the Foreign Policy of Postcommunist Kazakhstan,’ in Dawisha, A and Dawisha, K (eds),The Making of Foreign Policy in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. The International Politics of Eurasia Series, vol. 4, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, N.Y. and London.

Kazakhstan Emerges as a Major World Player. [20 Dec. 1999]: An Advertising Supplement, Washington Times.

Kazakhstan, MFARK (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan). [2008]: Cooperation of the Republic of Kazakhstan with the United States of America,’ Relations with Countries of Europe and America. MFARK (10-09-2008), Kazakhstan. Retrieved from http://portal.mfa.kz/portal/page/portal/mfa/en/content/policy/cooperation/europe_america/19 .

‘Kazakhstan-U.S. Investment Forum. [2009]: An official forum on U.S.-Kazakhstan investments, 23-24 November 2009, Harvard Club of New York City, New York, U.S.A. Program can be found online at <www.kazakhinvest.com>.

‘KBR Hired as Consultant by Kazakh Oil Producer. [4 March 2017]: KazWorld.info. Retrieved from http://kazworld.info, accessed on 5 March 2017.

Kessler, G., [15 May 2006.]: ‘Oil Wealth Colors the U.S. Push for Democracy,’ Washington Post.

Kukeyeva, F., and B. Zhulduz [2009]: ‘Realism and Middle Powers: A Case Study of Kazakhstan’s Foreign Policy,’ in Mohanty, Arun and Swain, Sumant (eds), Contemporary Kazakhstan: The Way Ahead. Axis Publications, New Delhi.

Legvold, R., [2004]: ‘U.S. Policy toward Kazakhstan,’ A discussion paper presented at: An International Conference on the Future of Kazakhstan’s Geostrategic Interests, Its Relations with the West & Prospects for Reform, 8-9 December 2004, Regent Almaty Hotel, Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Mankoff, J., [ Jan. 2013]: The United States and Central Asia after 2014, a report of the CSIS Russia and Eurasia program, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C.

NAC-KazAtomProm Annual Report 2015 2016, KazAtomProm, Astana.

National Guard. [March 2011]: ‘For the Media, Homeland Defense Fact Sheets, Global Engagement, State Partnership Program (SPP),’ Retrieved from http://www.ng.mil/media/ factsheets/2011/SPP%20Mar%2011.pdf

Nazarbayev, N., [16 May 1992]: ‘A Strategy for the Development of Kazakhstan as a Sovereign State,’ Kazakhstanskaia Pravda.

___________ [2001]: Epicenter of Peace. Hollis Pub. Co., New Hampshire.

___________ [1998]: Kazakhstan-2030: Prosperity, Security and Ever-Growing Welfare of All the Kazakhstanis, Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Washington, D.C.

___________ [2003]: The Critical Decade, First Books, London.

NCAFP. [2007]: Regional Security and Stability: Perception and Reality, a Roundtable on the U.S.-Kazakhstan Relationship, 4-6 March 2007, NCAFP, New York City, U.S.A.

Nichol, Jim 2013a, Central Asia: Regional Developments and Implications for U.S. Interests, CRS Report for Congress (RL33458), 9 Jan. 2013, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

___________ [2013b]: Kazakhstan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests, CRS Report for Congress (97-1058), 22 July 2013, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

Nysanbayev, A., [2004]: Kazakhstan: Cultural Inheritance and Social Transformation. The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, Washington, D.C.

Olcott, M. B., [1995]: The Kazakhs, (2nded.). Hoover Institution Press, Stanford U, Stanford, California.

___________ [2007]: Kazmunaigaz: Kazakhstan’s National Oil and Gas Company, A policy report of the Japan Petroleum Energy Center and The James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice U, Houston.

Oliker, O., [2007]: ‘Kazakhstan’s Security Interests and Their Implications for the U.S.-Kazakh Relationship,’ China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, 5(2).

Petroleum Kazakhstan Analytical Journal (PKAJ). [2016]: Retrieved from www.petroleumjournal.kz , accessed on 5 March 2017.

Potter, W.C., [17 Nov. 1995]: ‘The ‘Sapphire’ File: Lessons for International Nonproliferation Cooperation. Transition, 1(17).

Puchyk, K., [2 March 2017]: ‘Kazakhstan: A Leader in Global Nuclear Policy?,’ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved from www.thebulletin.org, accessed online on 5 March 2017.

Rashid, A., [4 Feb. 1993]: ‘The Next Frontier: Kazakhstan is a Magnet for Energy Firms,’ Far Eastern Economic Review.

Sagdiyev, B., [2007]: Borat: Touristic Guidings to Minor Nation of U.S. and A. and Touristic Guidings to Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, With Anthony Hines and Sacha Baron Cohen, Flying Dolphin Press/Random House, New York.

Sahib, H.M.A.B., [2016]: U.S. Relations with Central Asian States: A Study with Reference to Energy Resources Geopolitics from 1991 to 2012,’ Ph. D Thesis, University of Malaya, Malaysia.

Saudabayev, K., and N. Senator Sam (Foreword)., [2006]: Kazakhstan Nuclear Disarmament: a Global Model for a Safer World, Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, and Nuclear Threat Initiative, Washington, D.C.

Schreiber, D., and J. Tredinnick, [ 2008]: Kazakhstan: Nomadic Routes from Caspian to Altai. Odyssey Books/Airphoto International, Hong Kong.

Seisembayeva, A., [5 March 2017]: ‘In Kazakhstan, 35 of 40 Presidential Powers to be Redistributed under Final Draft Proposal,’ The Astana Times. Retrieved from www.astanatimes.com, accessed on 5 March 2017.

Shaikhutdinov, M., [2009]: ‘Kazakhstan and the Strategic Interests of the Global Players in Central Asia,’ Central Asia and the Caucasus. Retrieved from <http://www.ca-c.org/online/2009/journal_eng/cac-03/12.shtml>.

Shell Investor’s Handbook 2011-2015 2016, 14 July 2016.

Tarnoff, C., [1 March 2007]: U.S. Assistance to the Former Soviet Union, CRS Report for Congress (RL 32866). Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C.

The Sunday Times. [13 Feb. 2005]:Singapore.

The Washington Diplomat. [15 Jan. 2013]: Retrieved from <www. washdiplomat.com>, accessed on 18 Feb. 2017.

Tokaev, K., [2004]: Meeting the Challenge: Memoirs by Kazakhstan’s Foreign Minister, A.R. Shyakhmetov (trans.), Diplomatic Mission of Kazakhstan to Singapore, Singapore; and Keppel Offshore & Marine, Singapore.

Trickett, N., [16 Feb. 2017]: ‘Watch the Throne: Trans-Caspian Pipeline Meets Succession Politics in Kazakhstan,’ The Diplomat.

United States of America, CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). [1993]: Kazakhstan: An Economic Profile, National Technical Information Service (NTIS), Springfield, Virginia.

United States of America, DOC (Department of Commerce). [2008]: Statistical Abstract of the United States, NTIS, Springfield, Virginia.

United States of America, DOS (Department of State). [25 May 1992]: ‘US-Kazakhstan relations – joint declaration and Department of State statements,’ US Department of State Dispatch, U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C.

United States of America, DOS-BN. [April 2009]: Background Note: Kazakhstan, , Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/5487.htm, accessed on 31 Aug. 2009

United States of America, DOS-FOA., [1 June 2013]:‘Foreign Operations Assistance: Kazakhstan–Fact Sheet,’ Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs. Department of State (DOS), Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www. state.gov/p/eur/rls/fs/2013/212979.htm, accessed on 3 June 2014.

United States of America, DOS-FOA., [31 Aug. 2016]: ‘Foreign Operations Assistance: Kazakhstan–Fact Sheet. Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, Department of State (DOS), Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://2009-2017.state.gov/p/eur/rls/fs/2016/261453.htm, accessed on 4 March 2017.

United States of America, DOS-FOAA., [20 Jan. 2009]: ‘Foreign Operations Appropriated Assistance: Kazakhstan–Fact Sheet. Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, Department of State (DOS), Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/ p/eur/rls/fs/103634.htm , accessed on 9 Aug. 2013.

United States of America, DOS-USRWK., [16 Nov. 2012]: ‘U.S. Relations with Kazakhstan–Fact Sheet. Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, Department of State (DOS), Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/5487.htm , accessed on 9 Aug. 2013.

United States of America, EIA (Energy Information Administration).[ 26 Aug. 2013]: ‘Caspian Region,’ EIA Country Analysis Briefs. U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, D.C. Available online at <http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/Caspian/Full.html>.

United States of America, FTD (Foreign Trade Division). [2016]: ‘Trade in Goods with Kazakhstan. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/, accessed on 23 Feb. 2017.

United States of America, FRD (Federal Research Division). [1997]: ‘Foreign Policy,’ LOC Country Study: Kazakhstan, ed. Glenn E. Curtis, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/ cstdy:@field(DOCID+kzO, accessed online on 18 Aug. 2008.

United States of America. [2016]: The World Factbook 2016. CIA (Central Intelligence Agency), Last updated on 31 Dec. 2016, Retrieved from <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/ the-world-factbook/geos/ kz.html>, accessed on 12 Feb. 2017.

United States of America, USAID., [1997]: ‘USAID Country Profile: Kazakhstan. US Agency for International Development (USAID), Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.info.usaid.gov/countries/kz/kaz.htm, accessed online on 18 Aug. 2008.

USKBA (U.S. – Kazakhstan Business Association)., [2014]: Available online at <www.uskba.net>.

‘US Resettles Five Guantanamo Prisoners in Kazakhstan. [31 Dec. 2014]: Al Jazeera America. Retrieved from http://www.america.aljazeera.com, accessed on 3 March 2017.

Washington Post, various issues between the years 1951-1991.

Weitz, R., [2008]: Kazakhstan and the New International Politics of Eurasia. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, John Hopkins University-SAIS, Washington, D.C.

Weller, R. C., [2006]: Rethinking Kazakh and Central Asian Nationhood: A Challenge to Prevailing Western Views, Xlibris Corporation, Bloomington, IN.

Winrow, G.M., [1995]: Turkey in Post-Soviet Central Asia, RIIA, London.

Yazdani, E., [2007]: U.S. Democracy Promotion Policy in the Central Asian Republics: Myth or Reality? ,’ International Studies, 44(2).

Yerzhan, B.A., [2009]: ‘Foreign Policy of Kazakhstan,’ in Mohanty, Arun and Swain, Sumant (eds), Contemporary Kazakhstan: The Way Ahead. Axis Publications, New Delhi.

Including, 600kg of, previously, forgotten ones from the Ulba fuel fabrication plant at Ust-Kamenogorsk (today’s Oskemen), in 1994 under Operation Sapphire.

Given that nearly 500, of the about 1,000, Soviet nuclear tests took place in test sites across Kazakhstan, one may cautiously assume that, there are still hundreds of vents, if not also tunnels, to be properly secured out there. At least 86 of those tests were aerial, 30 on ground, 340, variously, underground; 498 tests were conducted and, it is said, about 616 devices were detonated, so in short the sums, disturbingly, appear a little difficult to add up!

In this context, Kazakh natives who have been under extra judicial detention in the U.S. base in Guantanamo for alleged ties to the Taliban and/or Al-Qaeda include Yaqub Abahanov, Ilkham Turdgyavich Batayev, Abdallah Tohtasinovich Magrupov and Abdulrahim Kerimbakiev. On this, see: <http://www.dod.mil/news/May2006/ d20060515%20List.pdf>. All these Kazakhs have subsequently been released. Like America’s other new friends in Eurasia, Kazakhstan too indulged a departure-poised Obama, by further accepting at least 5 Guantanamo non-Kazakhs transferees, such as the two Tunisians and three Yemenis that Kazakhstan accepted (‘US Resettles Five Guantanamo…’ 2014).

For an authoritative, if not also official, American interpretation of the context of the Kazakh input in the request, see National Committee on American Foreign Policy (NCAFP) 2007. See also Weitz 2008, p 125.

Beyond this research period, the NDN is headed for closure, if Dmitry Medvedev could be believed. Medvedev, ostensibly, adhering strictly to UNSC resolution 2120, issued his own resolution to close the NDN on 15 May 2015 (Daly 2015). If this were to come to pass, then Kazakhstan stands to lose about U.S. $ 500million per year in NDN transit fees. On the bright side, the U.S. wants the NDN under its New Silk Road Initiative to morph and work to integrate Afghanistan into not just the Central Asian region but also with China and Europe via Eastern Europe.

The outer and extra regional ports utilized chiefly include Poti, Tallinn, Riga, Klaipeda and it is believed even Vladivostok. When President Obama met President Nazarbayev on 11 April 2010 he praised Kazakh assistance to Afghanistan and Nazarbayev, in turn, promised to facilitate a new trans-polar flight route (see Map 1) for the transiting U.S. military (Nichol 2013b, p 21). An air transit agreement was signed between both parties on 12 Nov. 2010.

While in the West people may often confuse terms such as terrorism, extremism, separatism, radicalism and fundamentalism (with those italicized terms readily, but often misguidedly, being seen as threats), and at times irresponsibly use them loosely or interchangeably; in Kazakhstan, remarkably, their leaders are quite well-versed and do have a rather nuanced understanding of these distinct terms and the positive or negative implications they, to varying degrees, carry. Still, given the need to responsibly and clearly separate Muslim extremists, not to mention terrorists too, who, probably, operate at the behest of their sponsoring foreign Major Powers, from the Islamic, as distinct from the politically-focused Islamist, extremists, who merely function in pure devotion and conformity to the Shari’ah (Islamic law) alone; the Kazakh elites have recently taken to, quite rightly, differentiating and qualifying the former as not merely harmful extremists but as very dangerous violent extremists, if not also as clear terrorists.

See Nazarbayev, N., A Strategy for the Development of Kazakhstan as a Sovereign State. Kazakhstanskaia Pravda. Dated 16 May 1992, for details of Kazakhstan’s foreign policy model.

The expectations of some, Kazakh and foreign, interlopers that the 2012 promulgation of a “Leaders Day” might result in a steady handover of power, remains yet unfulfilled, as Nursultan Nazarbayev healthily deliberates on political albeit constitutional reforms (Seisembayeva 2017) and contemplates on the prospective 2020 elections. Given this reality, rumors of a name change for the national capital Astana has to remain at just that: a rumor going cold!

Beyond the present research period, this had somewhat come to pass. I.R. Iran’s deal with the powers came into force in Jan. 2016; under this deal, it is believed, Iran is allowed to run about 5,000 “IR-1” centrifuges, test advanced models and, perfectly, legally import yellow cake, but all under the strict watch of the IAEA.