A CONCISE INTERPRETIVE ANALYSIS OF U.S. – KAZAKHSTAN RELATIONS, 1991-2013

Hujjathullah M.H. Babu Sahib*

Abstract

The United States’ new interest in the Central Asian region has seen its relations with Kazakhstan, continually but incrementally, getting more important. The United States is having increasing ties with Kazakhstan in political, economic and strategic terms. These ties are reviewed here using a sector-oriented analytical lens, viewing in turn the origins of their diplomatic relations, their bilateral interactions, addressing, specifically, development assistance, trade, investments, business presence, energy dealings and their defense and security ties. This article, thereby, attempts to provide, simultaneously, a loose chronological, thematic and an interpretative analysis of the, clearly, broad-based United States and Kazakhstan relationship, noting there through also the changes taking place in it, over time. Geo-political aspects are mentioned, as and where necessary, contextually and the multi-lateral aspects of the relationship are merely hinted at, in passing.

Key Words: Kazakhstan, United States, Foreign Policy, Diplomatic Relations, Evolution of Relations, Bilateral Trade, Investments, Business Presence, Bilateral Development Assistance, Energy Dealings, Defense and Security Ties, Central Asian Region

Introduction

As one of the newly independent states (NIS) to emerge out of more than seven decades of political isolation under the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan is comparatively a new country to initiate and develop relations with the United States. Nevertheless, upon independence, Kazakhstan was quick in establishing a broad range of ties with the U.S., including in the political, economic and strategic domains. Despite the enormous distance and lack of direct land access, any boundary, not to mention a border, between Kazakhstan and the United States, both the countries have managed to develop an increasing trade relationship. The United States has given Kazakhstan much transformational and developmental aid under its various politico-economic and strategic programs. The United States has made significant investments in various energy related projects in Kazakhstan but its investments are, by no means, confined to the energy sector alone but instead also involves investments in industrial, business and services sectors too, often, initially, along with Turkish partners.

Even before Kazakhstan became independent, it had continually, if sparsely, figured in American media, including in the Washington Post, in the various contexts of: a) strategic developments within the Soviet Union, b) ecological and other disasters within the Soviet space, c) Gorbachev’s anti-corruption campaigns under glasnost and d) in the immediate past even in the context of Central Asian leaders’ reactions to the Gulf War (Washington Post, various issues). Incidentally, it was actually American media coverage of coup-affected Moscow that enabled Nursultan Abishuly Nazarbayev to save both Mikhail Gorbachev and then Boris Yeltsin too from falling prey to the trouble-making hardliners. Proving, thereby, that the U.S. even through its media had for long tuned in and been attentive to developments even within Soviet Kazakhstan, not to mention too, of course, catering to the informational imperatives of a Kazakhstan teetering at the verge of independence.

Actually, continuing the momentum of glasnost and perestroika, Gorbachev began granting greater degree of autonomy, from 1988 on, to the union republics of the USSR, including to Kazakhstan. Taking this up the Kazakh people established their own governing structures, determined their own future course by choosing their own national emblems and even declaring their sovereignty, finally on the 25th of October 1990. Though Western observers generally, both at Kazakh independence and immediately prior to it, have considered the Kazakhs as lacking in nationalistic spirit, in comparison to the Balts for example, and highly nomadic in their socio-political make-up to merit national independence, American elites in particular have shown some interest, given their long, praise-worthy, commitment to anti-colonialism, in an independent Kazakhstan and in wanting to establish separate relations with it (Olcott 1995, pp. 290-94; Weller 2006; Weitz 2008, p. 122 and p. 127). Thus, it came as no surprise, when the U.S. became one of the first nations to recognize Kazakhstan’s independence and to rapidly open diplomatic relations with it, thereafter.

Strategically and more, mutual relations have now proceeded beyond two decades and a half, rather amicably with only minor tensions along the way. Specifically, this article addresses the following questions: When and how politico-diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Kazakhstan took shape? How has these relations evolved since then? What are the various sectors of their economic relations? ; And how have vital energy and security issues fared in their strategic ties since the inception of their relationship? The structure of the rest of this article proceeds, henceforth, under three key rubrics, namely: Political Front, Economic Sphere and Strategic Realm. Each of these are further divided into sub-sections or sectors, i.e.: Political Front is divided into Political Recognition and Diplomatic Representation, Evolution of Relations Generally, and Bilateral Development Assistance; Economic Sphere consists of Bilateral Trade, Business Presence, and Investments; and the Strategic Realm is occupied by Energy Dealings, and Defense and Security Ties. This article ends with some concluding thoughts and proffers some integral but tentative suggestions therein.

Political Front

Though there had been a number of informal first encounters between U.S. citizens and Kazakh natives before and around Kazakhstan’s independence, their first formal diplomatic encounter, however, obviously had to wait for Kazakhstan’s, independence. When independence did come, alas, the United States was amongst the first countries to grant it its diplomatic recognition. Freed unwillingly of the yoke of Union and unsure of how to proceed ahead into the approaching twenty-first century without the protection of the Soviet umbrella, Kazakhstan earnestly embraced the welcome of the remaining superpower, the United States of America.

In fact, it was this very sense of non-confidence and unpreparedness for independent statehood that made Kazakh leaders, including the Gorbachev-loyal Kazakh nationalist Nazarbayev, having himself been in the chief executive slot only since 1989, to root, earlier and vainly, for a renewed Union (Olcott 1995, pp.264-265). Kazakhstan, like the rest of ex-Soviet Central Asia and the Caucasus, was instead, non-consultatively and unceremoniously booted-out, figuratively speaking that is, of the Soviet Union by the key Slav states, decisively so, after their Belovezh Conspiracy (Olcott 1995, p.270; Dave 2007, p. 8 and p.178 f. 4). Finding itself insecurely left out of the previously well-acclimatized Russian cold, Kazakhstan, for the same non-confidence, unlike the Baltic States, enthusiastically pushed for a looser confederal arrangement in the shape of a Russia-led Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a loyal member of which it remains till today.

Political Recognition and Diplomatic Representation

With the encouragement of the West, of western allies like Germany and Turkey and the increasing indifference of Russia itself to their fate, the Kazakhs declared their independence quite reluctantly on 16th December 1991, particularly, after the failure of the August coup against Gorbachev. Having had a paramount role in the Soviet endgame, it was somewhat surprising that the United States, led then by President George H.W. Bush, lagged behind states like Turkey and Italy in granting political recognition to an independence-poised Kazakhstan. According to Jonathan Aitken, Turkey was the first in this regard (Aitken 2009, p.125). When recognition was given to it finally, it came en mass, the United States recognized Kazakhstan along with the rest of the CIS on Christmas Day, 25th December 1991. Still, “the United States was the first country to recognize Kazakhstan on December 25, 1991 and opened its Embassy in Almaty in January 1992; the Embassy moved to Astana in 2006,” cleverly states the official Background Note of the US Department of State (DOS-BN 2009).

Nevertheless, at independence, unlike with the other Central Asian states, and despite the initial euphoria, the U.S. welcome of Kazakhstan was somewhat restrained, given Kazakhstan’s too high an affinity to a non-Gorby-led Russia, and was also critically underpinned demographically then (Olcott 1995, p. 265; Tokaev 2004, p. 125). Having established diplomatic relations with Kazakhstan relatively quickly the U.S. went on to open its diplomatic mission and embassy in its then capital Alma Ata (the present Almaty) in January 1992. Besides having its embassy/chancery in Astana, the US also maintains a consulate and regional offices of the USAID and Peace Corps at Almaty, in view of its closeness to the Kazakh concentrations in southern Kazakhstan and to the heart of the rest of native Central Asia. Similarly, too Kazakhstan has its embassy in Washington, D.C. and it has a consulate at New York, to be close to not just the world of American business but also to attend to the United Nations and partake in the business of global affairs, thereby.

The United States’ first resident envoy to Kazakhstan was William Harrison Courtney, who started his mission in Alma Ata as Charge d’ Affaires ad interim on 3rd February 1992, later the contemporary U.S. ambassador then was Kenneth J. Fairfax till somewhat replaced by Michael S. Klecheski. In between stints as the Foreign Minister of Kazakhstan Yerlan Abilfayizuly Idrissov also had served as Kazakhstan’s ambassador to the United States from July 2007 to October 2012. Recently, Idrissov stepped aside as foreign minister in favor of Kairat Kudaibergenovich Abdrakhmanov. Since 2015 George Albert Krol, a region-savvy, well-accomplished career Foreign Service specialist, has remained as the U.S. ambassador to Kazakhstan in Astana. Similarly, multi-stinting Kairat Yermekovich Umarov has been, till recently, his counterpart for Kazakhstan in Washington, D.C. (The Washington Diplomat 2013).

Trade relations began to take shape and U.S. exports to and imports from Kazakhstan gradually rose but only continually so. Not having common border has its impact on trade relations between Kazakhstan and the U.S. Having rather limited economically–sensible outlets to the world market including to those of the U.S., Kazakhstan in the initial years had rather limited volume of trade with the U.S. Thus, it was no surprise to find Russia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan figure as greater trade partners then of Kazakhstan. Nevertheless, Kazakhstan’s exports to and imports from the U.S. has rapidly, if continually, grown since its independence (as may be seen elucidated further in the later sub-section on Bilateral Trade).

Episodes of elite visits to either country usually mark upswings in relations. Besides periodic visits by top elites like presidents and cabinet members, there have been some visits and numerous authoritative statements by intermediate policy practitioners at the level of special envoys, deputy secretaries, assistant secretaries, deputy assistant secretaries of various relevant executive departments/ministries and security officials too, from, of and to Kazakhstan. Similarly, delegations of key members of the U.S. legislative branch have visited their counterparts in Kazakhstan and vice-versa. As you may see later, the re-election year 2004, for example, saw more U.S. elites visiting Kazakhstan. Despite the 5-years visa given, Kazakhstan is still not a visa-waiver country, indicating it has still some grounds to cover before it could be deemed a U.S. friendly-country; and hence Kazakhs visiting the US and vice-versa do need visas for mutual visits. Obviously, more steps need to be taken for both to keep in step!

Being among the more Russo-friendly Central Asian peoples and only recently having been freed from Soviet-imposed atheism, the Kazakhs, like the rest of Central Asia generally, take an evolutionary approach to inevitably but gradually rediscovering their Islamic faith and Muslim traditions. Having uneasily accommodated even the despicable atheism in their midst for so long, they have no trouble, unlike some of their Islamic brothers in the more orthodox areas of their Muslim periphery and beyond, at being tolerant of and accepting the presence of numerous minorities holding radically diverse faiths from theirs. Thus, Americans either visiting or stinting in Kazakhstan can easily observe the unmolested presence therein of adherents of not just the Russian Orthodoxy – the faith of their immediate past overlords – but also members of other churches of Christianity, e.g. Autocephalous Orthodox, Apostolic Orthodox (both of Eastern Orthodoxy), Protestant (of evangelical and Baptist varieties including Lutheran, Jehovah’s Witness and even Seventh-Day Adventist) and Catholic; Judaism, Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, the rather native Tengrism (Nysanbayev 2004, p.183) and Shamanism, and the blooming of all their various institutions and/or organizations in Kazakhstan. Conversely, Kazakhs visiting the U.S. can similarly see Muslims in general and Turkic-Muslims on average and members of even the Kazakh diaspora doing reasonably well in the United States. If Kazakhs can survive even in communo-atheistic Soviet Union till Gorbachev’s openness granted them overt practice then they certainly can flourish in god-loving, capitalistic America where no U.S. president, neither a Republican nor a Democrat, would hinder them from peacefully practicing their religion and extolling their faith, given that, after all, America, conveniently for the free-spirited Kazakhs, is both the modern Mecca for freedom of religion and, ironically, for freedom from religion too.

Evolution of U.S.- Kazakhstan Relations

Not wanting to offend Gorbachev, his partner in the Cold War endgame, George H.W. Bush was overly cautious in welcoming an independent Kazakhstan initially. Nevertheless, with his popularity slipping by the day and having just over a year of his term left, he rushed his secretary of state James Baker to Alma Ata to register America’s keenness on Kazakhstan nonetheless, and to serve to the Kazakhs the appropriate pointers for pursuing future co-existence. Baker, of course, met, literally, naked success in this during his “sauna diplomacy” with Nazarbayev! Unsurprisingly, in the initial year of ties there was not much of a trade figure to show for, though, like in the security sector, important agreements on trade, investment protection and avoidance of double taxation were signed. Given America’s disdain for the Political Islam espoused by Iran, the U.S. held up Europe and Turkey as models for the Central Asian states to emulate, as pointedly noted by Gareth Winrow (Winrow 1995, p.13). Nevertheless, having taken the full measure of, initially Western-backed and Russia-ignored, Turkey to help in their restructuring processes, Nazarbayev still, needfully, proceeded to Iran to develop a more lucrative economic relation with it in the wake of the Ankara Summit of October 1992.

Given the United States’ long running obsession with non-proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), and also with an eye on Central Asian strategic realities, the U.S. enacted a facilitating legislation: the Nunn-Lugar Act. Later, in pursuance of this, the United States made a priority of effecting nuclear threat reduction in Central Asia particularly, though not exclusively, so in Kazakhstan. H.W. Bush’s administration did not extend much, in terms of aid, to Kazakhstan but Nazarbayev was aware of and, helped much by the Nunn-Lugar-visit, was determined to get Kazakhstan’s fair share of whatever was given out as CTR aid. In Kazakhstan itself their elites were quite divided into hawks, bargainers and doves on the nuclear issue (Tokaev 2004, p.128; Aitken 2012, p.79). Some, including Nazarbayev himself, well aware of the pre-independence Nevada-Semipalatinsk movement, were only too keen to rid Kazakhstan off these standing symbols of Soviet administered radioactive, environmental and health abuse of Kazakhstan (Nazarbayev 2001; Saudabayev and Nunn 2006). Others, more cognizant of Kazakhstan’s geopolitical vulnerability, in a growing nuclear neighborhood, and aware of the bargaining value of even under-maintained Soviet/Russian nukes, slated for destruction under START, thought otherwise. For these legitimate reasons, Kazakhstan took its time, first, in renouncing nukes, then, further delaying the total removal and/or conversion and varying destructions of its strategic weapons and their associated components.

The Freedom Support Act (FSA), which largely duplicates the earlier language of the CTR program legislation (P.L.102-228), is a facilitating legislation enacted, in a timely fashion, to give substantive backings to pursue America’s diplomatic and politico-economic missions in the newly independent nations of the ex-Soviet Union, including in Kazakhstan. The United States took the early disinterest of Russia on Central Asia, in general, and in Kazakhstan, in particular, as a sort of cue and moved ahead, if hesitantly, to build a broad-range of ties with all the NIS of Central Asia. This fact, is reflected in the broad politico-economic coverage of the FSA (P.L.102-511) of 1992, though, Russia was still its intended primary beneficiary, more so by default than by design, it appears. Anyway, Russia was also not too much disturbed by the initial American interest in the ex-Soviet space and especially by the facilitating structure of the FSA because, in the early years, this initiative, as mentioned earlier, was, as if intended to appease, primarily Russia-centric.

This was not surprising given that Russia was, undeniably, the pre-eminent state to emerge from the disintegrating Soviet Union and that all the other successor states were much inferior to it in their politico-economic weightage. Russia was also the United States’ working partner in ending the original Cold War episode and, along with other Slav states, the prime mover of the Soviet end-game. But having eased the Soviet collapse and helping Russia towards finding its proper nationally-independent albeit reduced space and place in the international community and its various institutions, the U.S. also felt that it should do likewise to the ex-Soviet rest, particularly, to key states like Ukraine and Kazakhstan. As the years passed and as things evolved, in that reconfigured space, the need to pay greater attention to these key states and the rest of the non-Russian NIS also grew apace. Unsurprisingly, the U.S. went on, in later years, to reinvigorate its diplomatic relations and further extend its presence in the NIS generally, and particularly so, variously, in the Central Asian states. The U.S. was overly keen on Kazakhstan, along with Russia, given both their overwhelming territories and the obvious natural resources that these represent. In the context of ex-Soviet Central Asia, Kazakhstan was, somewhat inexplicably, also given a greater priority, by the ostensibly market-focused US, initially, than Uzbekistan, which clearly has a larger population and, by implication, a bigger market (Legvold 2004, p.1).

In 1993, the U.S. Department of Defense, wanting to gain friendly access to a newly-freed region, used its National Guards SPP (1991), that grew out of EUCOM, to lure the former Soviet republics, including Kazakhstan, to participate in its program (National Guard 2011; Balaban 2012). In doing so, it perhaps encroached on some of the much earlier interest there of the U.S. Dept. of State, giving rise to a latent inter-Departmental turf war of sorts. The U.S. media, while sharing the coolness of the American government towards Kazakhstan, also covered the dealings of U.S. oil firms in Kazakhstan’s energy sector, besides also noting, quite uneasily, Kazakhstan’s continued sheltering under Russian hegemony, if not imperialism too, as disturbingly symbolized by the on-going lease of Baykonur Cosmodrome to Russia. More on these, in context, would be dealt with, in the later section on Strategic Realm.

The first William J. Clinton administration, not wanting to be left out of the loop, for its part, had Strobe Talbott and Warren Christopher making a beeline to Alma Ata (later Almaty) quite early too. However, it is believed that Nazarbayev, seeing Christopher to be relatively a weak player in the U.S., sent him back to the U.S. to fetch vice-president Albert Arnold Al-Gore, for signing any more pithy agreements like the Disarmament and Democratic Partnership ones, which were signed later on (Aitken 2009, p.143). This keenness on the U.S. Democratic side was also amply reciprocated by the Kazakhstanis when Nursultan Nazarbayev established a pattern of, mostly biennial, visits to the U.S. during Clinton’s total tenure. His foreign minister in those times Kassymzhomart Kemeluly Tokaev also engaged his counterparts in both Clinton administrations. During these visits they met top U.S. elite in-charge of the State, Defense, Energy and Commerce departments. In the security sphere, Clinton’s astute secretary of defense William Perry was particularly instrumental, in proposing a regional non-aggression pact (Kasenov 1995, p. 278) and also, in over-seeing the top-secret Operation Sapphire (1994), involving the sale of Kazakh HEU, roughly sufficient for making 25 atomic bombs, to the U.S. (Potter 1995). The U.S. was delighted, again in 1994, when Kazakhstan joined NATO’s PfP program, thereby displaying Kazakhstan’s relative capacity for independent foreign policy action (Yerzhan 2009, p.13). Though Russia was uneasy about this, it drew some consolation, in the initial years at least, from the fact that this was not the NATO of old and that it no longer appears to be arranged against Russia and that NATO now is more poised to tackle out-of-area responsibilities. On Kazakhstan’s part, it too, not wanting to appear as moving too close to the West, tried to balance such sentiments by proposing a Eurasian Union and later joined a Russia-led Customs Union too in May 1995, under the same spirit.

With the confidence of Western, especially American, support and aid tucked securely under his belt Nazarbayev cancelled the scheduled election and went for a referendum to consolidate further his rule, instead. It was perhaps under this sense of confidence too that Kazakhstan oversaw successfully the last nuclear “blast” or rather destruction, in May 1995, in its territory, though some Kazakhs did have their reservations about their compliance to these earlier joint U.S.-Soviet strategic undertaking and consequent obligations. Clinton, the First Lady that is, also took U.S. –Kazakhstan ties up, along a different dimension, when she toured Kazakhstan. She, in particular, can be credited with the start of a parade of high-powered petticoats into Kazakhstan; for her precedent was later competitively followed up by the likes of Condoleezza Rice and Madeleine Albright, with the latter curiously and particularly incensed over Kazakh sale of even old MIGs to North Korea. During both Clinton administrations, trade saw steady but continual growth with the United States registering both surplus and deficit balances with Kazakhstan. There were relatively remarkable trade volumes notched up in both 1997 and 2000 (see Table 1, later). In terms of aid, the U.S. extended relatively high amount of aid in both 1994 and 1995. It began declining after 1996 with it again picking up thereafter only in 2000 (Nichol 2013a, p. 65).

Though Kazakhstan has a policy of positive cooperation with all its neighbors and the great powers, since its independence, its relations with the United States has generally been quite amicable but interspersed with brief periods of lukewarmity if not actually neutrality. In this context, Western observers have noted Kazakhstan’s cold-shouldering of even Russia on occasions. But more on this would be seen in the section called Strategic Realm, coming later.

Table 1: U.S. – Kazakhstan Trade Value (in millions of U.S. dollars)

Year |

Value |

Exports |

Imports |

Balance |

|

||

1992 |

35.5 |

14.9 |

20.6 |

-5.7 |

|

||

1993 |

109.2 |

68.0 |

41.2 |

26.8 |

|

||

1994 |

192.8 |

130.3 |

62.5 |

67.8 |

|

||

1995 |

203.8 |

80.9 |

122.9 |

-42.0 |

|

||

1996 |

259.4 |

138.3 |

121.1 |

17.2 |

|

||

1997 |

475.1 |

346.2 |

128.9 |

217.3 |

|

||

1998 |

271.8 |

103.1 |

168.7 |

-65.6 |

|

||

1999 |

408.8 |

179.6 |

229.2 |

-49.6 |

|

||

2000 |

553.2 |

124.2 |

429.0 |

-304.8 |

|

||

2001 |

512.3 |

160.3 |

352.0 |

-191.7 |

|

||

2002 |

939.4 |

604.8 |

334.6 |

270.2 |

|

||

2003 |

560.7 |

168.2 |

392.5 |

-224.2 |

|

||

2004 |

859.0 |

320.4 |

538.6 |

-218.2 |

|

||

2005 |

1,639.4 |

538.3 |

1,101.1 |

-562.9 |

|

||

2006 |

1,606.8 |

646.2 |

960.6 |

-314.5 |

|

||

2007 |

2,004.3 |

752.8 |

1,251.5 |

-498.7 |

|

||

2008 |

2,588.9 |

985.5 |

1,603.4 |

-617.9 |

|

||

2009 |

2,147.0 |

603.5 |

1,543.5 |

-940.0 |

|

||

2010 |

2,602.7 |

730.3 |

1,872.4 |

-1,142.1 |

|

||

2011 |

2,506.4 |

827.1 |

1,679.3 |

-852.2 |

|

||

2012 |

2,448.6 |

883.6 |

1,565.0 |

-681.4 |

|

||

2013 |

2,571.6 |

1,150.2 |

1,421.4 |

-271.2 |

|

||

|

|

||||||

2014* |

2,418.7 |

1,007.9 |

1,410.8 |

-402.9 |

|||

2015 |

1,326.6 |

510.5 |

816.1 |

-305.6 |

|||

2016 |

1,853.4 |

1,111.1 |

742.3 |

368.8 |

|||

Grand Total |

31,095.4 |

12,186.2 |

18,909.2 |

-6,723 |

|||

Notes: * - These updated data have been made to stand differentiated from those of the original research period (1991-2013); the grand total, of course, includes all the updates. All figures for the latest 2 to 3 years are liable to be subsequently revised and adjusted, as per usual practice, as fresh data become available. Cf. Figures given by EKUSA, however, are higher for Export and lower for Import, it must be noted (EKUSA 2016).

Sources: Adapted, calculated and presented by the researcher from the raw data-set given by the DOC (U.S. Dept. of Commerce) 2008, Statistical Abstract of the United States, NTIS, Springfield; Census Bureau 2016, U.S. International Trade Data, Foreign Trade Division (FTD), Available online at: <https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/>.

With the Bushes back in power in Washington, Nazarbayev, perhaps a little unnerved by the regional impacts and ominous implication of the Sept. 11 attacks, rushed to Houston to pay sincere homage to one of his initial American friends, H.W. Bush and then onwards to Washington, to meet the son, President George W. Bush and his powerful team of advisers, on official business. The U.S. had been obviously pursuing a number of objectives in Afghanistan long before then. Inter alia, it apparently wanted to undermine the Taliban regime and put pressure on it to abandon the Al-Qaida; the Americans also wanted to raise Pakistan’s dependence on them; they wanted to undermine the influence of Iran and its allies therein and thereabout; and obtain a reliable foothold in and secure a possible springboard thereby to move further into the emergent Central Asian region. Subsequent developments in the larger region show the pertinence of these objectives in themselves, if not also in their total realization.

Pakistan or important elements within it had a pre-eminent role in the transformation of the Taliban religio-social movement into a menacingly potent force capable of seizing and projecting its power right across Afghanistan and, debatably, beyond. Kazakhs discovered this disturbing capability more than a decade later when, responsively and responsibly, the Kazakhstan Senate reversed its earlier decision to commit Kazakh officers to the ISAF in Afghanistan in uninitiated disregard of Taliban sensitivity (Nichol 2013b, p.24). Though Pakistan was the main conduit for weapons and supplies reaching the Taliban from its rather few backers in the international community, yet very few would doubt that Pakistan could have sustained its deep involvements and backing of the Taliban that long, without the support in kind, if not just in cash, of America or some influential elements within it.

These facts are not lost on the Central Asians in general and the Kazakhs in particular. Thus, when Pakistan dramatically and painfully swung away from the Taliban in the aftermath of the tragedies of Sept. 11, 2001, Pakistan- a widely-acknowledged sponsor of the hostile, if not also retrograde, Taliban- could without much difficulty reconcile with and rebuild up its relations with Kazakhstan and the rest of the Central Asian states. As unlikely as it may seem, the Taliban, given their perceived political immaturity, unwittingly, served as the catalyst for development of closer Pakistan-Central Asia relations. An anxious albeit Indo-Israeli inspired U.S. showed its bewildered appreciation, for this clearly painful and hesitant Pakistani swing, nevertheless, as can readily be discerned from the American media.

Earlier on, it must be noted that, the U.S., clearly under similar lobbistic pressure, had supported another antagonist in the Central Asia/Caucasus periphery. From even before Central Asian independences, America has had sympathies for the Armenians rebelling in Nagorno Karabakh and agitating for uniting with an Armenia that was uncertainly poised for independence. American feelings, if not also strong support, for the Karabakh rebels, obviously served to increase Central Asian doubts on American neutrality in and about their region.

Having cleared all the initial diplomatic formalities and early treaty and relational milestones, quite rapidly, if also cautiously, U.S. - Kazakhstan relations, despite having brief hiccups, have continuously galloped along with growing amity. However, since 2004, relations have noticeably changed for the better. With mutual confidence being somewhat at a higher level during G. W. Bush’s first administration, Nazarbayev made fewer personal visits to the U.S. but this period saw a higher number of other elites from either side making visits, to take Kazakhstan-U.S. ties to another level. For starters, in the said year, there was a sudden parade of security-related elite visits from the U.S. to Kazakhstan. Key officials like Colin Powell, Donald Rumsfeld and Richard Armitage and important generals like John Abizaid, Richard Myers and Lance Smith all went over, some repeatedly so.

Perhaps, this activism was merely linked to the bigger number of treaties signed between the U.S. and Kazakhstan the previous year, loosely reflecting the situation a decade before, when similarly a big number of treaties were signed between the U.S. and Kazakhstan, but were then more typical of nations establishing relations and freshly putting their initial ties on proper, if also strategic, tracks. Anyway, it must be noted, hopes of a rapid and sustained improvement in relations between the U.S. and Kazakhstan were somewhat dashed with the outbreak of the Iraq War. Though this caused some tension in government circles, it did not lead to anything even remotely resembling an estrangement between them, but this is not to say that the entire Kazakh heterogeneous society took this U.S. aggression on its stride. At the social level, there certainly was much palpable unease at seeing a fellow Muslim state being attacked by the very superpower that was making clear introductory and sustained overtures to their own hardly-settled government.

This is markedly different from their perception of the earlier American involvement in Afghanistan, especially so their record and behavior towards the Taliban regime there. U.S. intervention then and their involvements therein thereafter, in post-Taliban times, constitute one of America’s costliest involvements ever in the erstwhile Third World, albeit in yet another Soviet-vacated theater. This represents, presumably, a positive case where American sponsorship of aggression helped upset and undo a local balance of power and imposed a rapid and decisive result in a Third World setting that was disturbingly poised to slip into a horrible Fourth World. In the eyes of outlet-seeking Central Asians, including the Kazakhs, though the U.S. did not deploy much ground forces there, they were anticipatingly amazed at America’s projection of its phenomenal air power and special forces and its ability to mobilize even the largely Muslim, if not also necessarily socialist, masses to drive out a patently retrogressive, albeit, questionably religious, Islamo-capitalistic regime. For these reasons, as the United States began its Afghan operation; “Kazakhstan offered the U.S. overflight and basing, although the latter did not prove necessary, due in large part to Kazakhstan’s geographic location being less than ideal for U.S. needs. The end of Taliban rule in Afghanistan was certainly viewed as beneficial in Almaty(…)” (Oliker 2007, p. 67)

During G.W. Bush’s second administration, U.S. elites visiting Kazakhstan were more representatives of the politico-economic sector. With people like Condoleezza Rice, Dick Cheney, Samuel W. Bodman, Richard Boucher and even the old-hawk Henry Kissinger swooping in, just to name a few. The U.S. was rather cold to Kazakhstan’s proposal and spirited efforts for the creation of the Eurasian Union. There was nothing surprising in this in the sense that the U.S., despite working cooperatively with Russia in the region, has always been quite uneasy with all schemes aimed at keeping the C.A. states tied too close to the Russian bosom. What is strange, however, is that the U.S. is also quite averse to Kazakhstan’s growing closeness, since at least 2006, even to the, clearly more Western-oriented and U.S.-led, OSCE too! U.S. aid to Kazakhstan was already rising even before G.W. Bush took over the White House. It rose significantly in 2004 as Bush entered his re-election year, but the highest aid during his entire tenure in office came when he went lame-duck in 2008 (Nichol 2013a, p. 65). Remarkably, bilateral trade during G.W. Bush’s tenure grew exponentially, and continually, with significant rises recorded in 2002, 2005 and in 2008. Other then in 2002 the U.S. trade deficit trend with Kazakhstan continued throughout both his administrations (again see Table 1, later).

To continue the Democratic Party’s own past engagement with Kazakhstan and wanting to exceed even Clinton in this respect, president-elect Barack Obama included Nazarbayev in his introductory calls to world leaders. But coming into office on a largely domestic-change agenda, he had to wait two years before he could receive Nazarbayev in Washington. In 2010 Nazarbayev got the, long overdue, reception he deserved as the model leader of a nation that had the courage to renounce even status-enhancing nuclear weapons. A brave undertaking in the interest of humanity, to be sure, but indeed an accomplishment in which the United States itself compares most miserably. Still, perhaps in exchange, the U.S. got the NDN, i.e. Northern Distribution Network (please see, Map 1), over-flight rights and a consulate general in Almaty. A month earlier, Washington had, of course, launched the Annual Bilateral Consultations (ABC), the Democrat’s own initiative to take U.S. - Kazakhstan ties to a higher plane, politically. This trend continued when the 3rd ABC in 2012 upgraded itself significantly to a Strategic Partnership Commission (SPC), signaling thereby that ties are getting more mutually pro-active (EKUSA 2012; EKUSA 2013). With the conclusion of the Strategic Partnership (now a) Dialogue, later at New York on 20 Sept. 2016, their mutual commitments continue to deepen further.

Having seeded for the OSCE chairmanship in 2006 through the, strangely highly–reluctant, second G.W. Bush administration, Kazakhstan got the chairmanship later and hosted the OSCE summit in 2010, in its desire to not just work for regional conflict-resolution at the Central Asian level but to attempt to do so, at the all-European regional level too. Kazakhstan had mixed results in this ambitious endeavor however, but still the Europeans, in general, and Mrs. Hillary Clinton in particular, who, this time as the sixth visiting U.S. Secretary of State, leading the U.S. delegation to the summit, was full of praise for Kazakhstan’s achievements, notwithstanding the various shortcomings in its net outcome. Many leading Americans like Ray Mabus, Robert O. Blake, Jr. and Simon Limage besides others have later followed at the heels of, the rather Central Asian foot-loose, Mrs. Clinton to Kazakhstan.

While the trade growth achieved in G.W. Bush’s later tenure somewhat bled into Obama’s own first term, at the cost of, initially, a higher trade deficit, overall trade values maintained their rising high levels, as Obama settled into his term of office, but with the significant outcome of a steady reduction in their trade deficit with Kazakhstan, helped by gradually rising exports and declining imports, as Obama approached his re-election year (see Table 1). As far as aid is concern, Obama’s first administration, in keeping with its predominantly domestic priorities, oversaw a gradual decline in U.S. assistance to an otherwise increasingly prosperous and regionally, if not also nationally, stabilizing Kazakhstan (Nichol 2013b, p. 23; Nichol 2013a, pp. 64-65).

Kazakhs note America’s recent, more moderated, approach to the Muslim world and energy security issues, with a sense of relief (Shaikhutdinov 2009). During Nazarbayev’s 2010 visit to Washington, D.C. to attend the Nuclear Security Summit, he was also given an award by the East West Institute for “championing preventive diplomacy and promoting interfaith dialogue at the global level” (EKUSA 2010). But, still, Barack Obama’s keenness to drawdown from Afghanistan is viewed with some concern as to what this may actually augur for the Central Asian region generally in the future, though Kazakhstan, in the meanwhile, rakes in more than U.S. $125 million per annum officially just from the U.S., for its role in permitting the “reverse transit” via NDN (a logistics arrangement originally begun in Jan. 2009 which subsequently has been operating in reverse mode since 2012) of “sustainment and total cargoes” exiting from Afghanistan (Mankoff 2013, p.4). Hemmed-in by an unfavorable, if not totally hostile U.S. Congress, the United States under Obama, in his second term, and Kazakhstan too, were somewhat constrained mid-2014 onwards, perhaps due to depressed oil prices, and could not both boost their increasing mutual ties, respectively, to the desired levels. Still, both the U.S. and Kazakhstan marked their 25th anniversary of establishing diplomatic relations by announcing reciprocal introduction of 10-year business and tourism visas to each other’s citizens, thereby, showcasing the robust nature of their on-going relationship.

Having assured Nazarbayev of his desire to strengthen U.S.-Kazakhstan ties quite recently, as the president-elect, Donald Trump, a little later, as the 45th U.S. President, perplexingly, settles into an apparently anti-Muslim posture, as he, assiduously, pecks out his obviously conservative albeit, paranoidly, xenophobic, emergent Republican administration. Where exactly would this latest U.S. presidential bogie take U.S.- Kazakhstan relation to?; only time would reveal. Meanwhile, all worldly-wise cosmopolitans would have to join the debate and energetically surf the anxious currents leading towards Expo2017, not least via #USKZ and #KZUS!

Bilateral Developmental Assistance (BDA)

The U.S. enacted the FREEDOM Support Act (FSA) in October 1992 to serve as the legislative cornerstone for its efforts to help the FSU in their political and economic transformations, as independent successor states of the collapsing Soviet Union. In this context, under the FSA the U.S. was committed to aiding Kazakhstan’s transition to democracy and to its reconfiguration as an open market economy. In fact the US has assisted Kazakhstan right from its independence. By the end of 1992 it had extended a modest figure of 20.33 million, in this regard. The AEECA-linked FSA had formed a significant percent of the United States’ total aid to Kazakhstan, over the years.

The U.S. government has been providing various bilateral development assistances to Kazakhstan not just principally through its various executive departments such as State, Defense and Energy but also through its other agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). In keeping with America’s neo-liberal agenda, the Agency’s program in Kazakhstan emphasizes a number of themes such as: a) private sector-led economic growth that is sustainable, b) accountable governance that is also effective, c) promote market reforms including liberalization, d) establishing the base for an open, prosperous and democratic society in Kazakhstan, and e) security help. The U.S. had provided around US “$1.205 billion in technical assistance and investment support” to Kazakhstan between the years 1992 to 2005 (DOS-BN 2009).

Since Kazakhstan’s independence the total U.S. government aid, in grant form mostly, including those that the USAID had extended to it till 2012 is fully valued higher at about US $ 2.09 billion. The peak year for aid thus far appears to be 2009 when Kazakhstan received U.S. $ 220.28 million (Nichol 2013a, p.65). Aid has drastically fallen since then, but follows a trend which first appeared in 2002. U.S. government aid between 2013 and 2015 add up to US$ 33,090,000. Though US$ 9.1million was appropriated for Kazakhstan in 2016, only a paltry US$2.29million was actually disbursed. An aid of just 8,783,000 has been requested for FY2017 (DOS-FOA 2016). Though these in themselves appear to be negative, these merely indicate the fact that other than on human rights issues, Kazakhstan has progressed, achieved economic growth, is democratically better than Russia itself, has an increasing security strategic value and that U.S.-Kazakhstan relations have stabilized more substantively to embrace numerous other sectors and are no longer merely confined to a developmental aid dependency relationship (Tarnoff 2007, pp. 4, 7-10).

The U.S. Peace Corps, often touted worldwide as promoters of peace, friendship and understanding between the U.S. and other countries, also ran its program in Kazakhstan since 1993, as per the request of that government, following initial presentation by the Peace Corps staff. A bilateral agreement codifies and consolidates further the works of the Peace Corps in Kazakhstan. Since independence numerous PCV groups have successfully served in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan had about 140 volunteers in 2009 engaged in various activities including in imparting business education, teaching English, public health, HIV/AIDS prevention, life skills education, community development, developing environmental NGOs and youth development (DOS-BN 2009). As one of the most well developed states in the world to host a Peace Corps program, Kazakhstan cumulatively saw, depending on the source relied upon, anything between 1,120 and 1,176 volunteers serve on its territory, before suspending their program in 2011.

More generally, U.S. foreign assistance programs in the form of technical assistance and development co-operation supports democracy building and promotes long-term development in various sectors such as agriculture, health care, education and environmental protection. The U.S. is also known to contribute to international institutions’ multi-lateral efforts to combat TIPs and even to private organizations working in Kazakhstan. Again, in a multi-lateral context, the U.S. commits to and supports the World Bank, IMF, EBRD, ADB and other such institutions’ aid to Kazakhstan too. In this context, other than the official U.S. bi-lateral and multi-lateral agency donors of development assistance, there are also private donors and philanthropic foundations in the U.S. that are involved in the Kazakhstan development sector. Such U.S. foundations, constructively engaged in Kazakhstan, include the Bill and Melinda Gates, Eurasia, Ford, Shelby Cullom Davis, Rockefeller, Soros, John and Catherine MacArthur and Asia foundations. Furthermore, hundreds of United States-linked NGOs are involved in capacity-building, including through offering training, and exchanges with Kazakhstan.

American BDA on the Political Front - The main objective of their co-operation in the political sector is the consolidation of democracy and promotion of good governance via supporting sustainable economic, social and environmental development. USAID has long supported anti-corruption project and also runs leadership and professional training courses for Kazakh mid-level elites. American help also goes to improving the skills of registered political parties and their officials. On Kazakhstan’s part, one-third, about a thousand, of all Bolashak scholarships, holders of which may turn out to be future leadership material, it offer are slated for higher studies in the U.S. alone. In the area of legal reform, promotion of rule of law is an overriding objective. USAID funding has also been used on the judiciary, to enhance their efficiency and effectiveness and to upgrade their skills at adjudicating cases, especially commercial cases and also, more generally, on reforming commercial law. The U.S. provides such assistances that, it believes, would win the judiciary, greater trust in the eyes of the Kazakh public.

Kazakhstan civil society and media development is enabled by U.S. technical assistance, on legal and regulatory reforms, addressing those sectors. The U.S. encourages citizen participation in the Kazakh public arena through its support of local NGOs. Other NGOs dealing with development of “independent media, legal reform, woman’s rights, civic education and legislative oversight” are also supported by the U.S. with generous grants. Specifically, through these engagements, the U.S. seeks to encourage the civil society in Kazakhstan “to influence national-level public policy decision-making” (DOS-FOA 2013). At the grassroots level, the U.S. helps in addressing local disputes, securing respect for human rights, promoting civic activism and facilitates coalition-building among local NGOs. Media institutions are funded to increase the public’s access to objective news and information. Very broadly, American aid in the Kazakh politico-legal sector includes encouragement of democratic political development and imparting of political skills, promoting the public role of civil society and the mass media; and improving the functioning and independence of the Kazakhstan judiciary. For other American BDAs, but specifically, for those addressed to the Kazakh econo-environmental sector and the BDA for its defense and security sector, please see at the ends of the following Economic Sphere and Strategic Realm sections, respectively.

Economic Sphere

America’s relationship with Kazakhstan is not limited to just the political but also has a consequent economic dimension. With the Soviet collapse, the successor states, including, Kazakhstan were enticed to the open-market way by the Western world. Kazakhstan’s moves towards economic development also through regional cooperation quite easily harmonized with U.S. policy for that entire region. Economically, Kazakhstan is key to the U.S. in the region because of its location, its economic bravery and dynamism, its higher industrial capacity, its array of natural resources, including energy ones and its low-density territory. The post Soviet collapse’s decline in demand, that reached its nadir in 1994, was overcome with bold economic reforms and more than reversed from 2000 on with the help of the rising energy sector, aid inflows, foreign investments and even improving harvests.

Utilizing the opportunity that came its way, as a consequence, the U.S. rapidly forged economic links with Kazakhstan that includes seizing investment opportunities, establishing and building trade ties, to gradually induct Kazakhstan towards the open market world trading system and promoting private-sector led business culture in Kazakhstan, by facilitating the presence and legally safeguarded growth of American and U.S. – linked businesses in the Kazakhstan market place. It is these economic sector moves and resultant ties that I would now discuss in greater depth.

Bilateral Trade

Kazakhstan and the U.S. are new but fast growing trade markets for one another. The trade value as represented by both the export value and import value of goods between them shows continual growth. As per the records of the U.S. Census Bureau, from the time when trade figures became available for Kazakhstan, i.e. from February 1992, just over a month after the US recognized it, US bilateral trade in goods with it had grown continually (FTD 2016). The export value of goods from the US to Kazakhstan grew continually from 68 million US dollars in 1993, the first full year of exports to be recorded, to US$1,150.2 million in 2013. After sliding down in 2014, exports again began bouncing up in 2016 with the visually-pleasing value of US$1,111.1 million, but well beyond the research period. The upward growth trend dipped only in the years 1995, 1998, 2003, 2009 and in the twin down years of 2014/5, in between.

Though the US is not among the top three of Kazakhstan’s export markets, it did figure as the third leading import market of Kazakhstan after Russia and Ukraine. The import value of goods to the US from Kazakhstan also grew continually from about US$ 41 million in the first full year of trade in 1993 to some 1,421 million dollars in 2013. The import value began growing exponentially from 2005 on continually, reaching a remarkable peak of sorts at US$ 1,872.4 million in 2010. The upward trend dipped somewhat significantly only between the years 2001 to 2003. Thereafter it has again been tapering down since 2011. On average the peak months for US exports to Kazakhstan are Februarys, Septembers and Octobers and the persistent peak months for US imports from Kazakhstan is Aprils. Overall, in 1993 bilateral trade was valued at a meager 109 million US dollars but with a US surplus. Most US surpluses, however, continually ran out by 1998 when the US began its protracted deficit run, in its bilateral trade with Kazakhstan, breaking the duck, alas, only in 2016, i.e. well beyond the research period. Earlier, in 2002, against the trend, the US had registered a surprise surplus too, perhaps as an unanticipated positive outcome, of the tragic Sept. 11 episode.

Viewed in a 5-yearly perspective, bilateral trade so far was valued at US$203.8 million in 1995; in 2000 it was 553.2 million; in 2005 bilateral trade was valued at US$1.64 billion, a 91% increase from 2004. Under the Cold War vintage Jackson-Vanik Amendment to Sections 402 and 409 of the 1974 U.S. Trade Act, Kazakhstan, by extension, was expected and has always more than complied with its freedom of emigration provisions and, accordingly, secured U.S. presidential certification to that effect, each time in the past. As a symbolic boost to the gradually rising U.S.-Kazakhstan trade relations, their 2006 agreement specifically excluded Kazakhstan henceforth from this amendment and its expectations, thus doing away with the need for a waiver to receive MFN treatment and actually graduating towards the WTO (EKUSA 2013). In 2010 trade was valued at more than 2.60 billion and in 2013 it slid a little to rest at about US$2.57 billion. Beyond the research period, it hit a low of sorts at US$1.33billion in 2015 before bouncing a little to be at US$1.86billion in 2016 (FTD 2016). The general upward trend saw relatively small, if not slight, dips in the years 1998, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2009 and 2011.

Though the growing trade figures are remarkable in themselves, these are still miniscule in comparison to the United States’ trade figures with older and longer well-established states like those in Eastern Europe and the Baltics, not to mention with heftier partners elsewhere in the world, least of all with the emerging economic powerhouse, neighboring China. Thus, the prospects for US-Kazakhstan trade in the future looks certainly bright, especially given broadly the United States’ keenness to diversify its various trades, encourage emergent economies and brace up the independences of the ex-Soviet states. When one looks at Kazakhstan’s trade partners, Russia still figures as Kazakhstan’s leading trade partner, overall. The E.U. and China follow Russia, in this respect, but with China fast aiming to out-strip both! The United States and its proxies Turkey, U.K., Germany and S. Korea also figure, as key import partners of Kazakhstan.

Without using the strict and comprehensive, if not also cumbersome, classification of trade products employed by the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC), one can generally say that trade between western countries, including the United States, and Kazakhstan are dominated by oil, ferrous & non-ferrous metals including uranium, machinery, minerals, industrial materials, gas, chemicals, electronics and transport vehicles. Specifically, in the case of the United States, the transportation vehicles deal, of General Motors and General Electric, respectively, comes to mind, in this context (EKUSA 2013). Somewhat lower down the rank, traditional agricultural products such as grains, including preeminently wheat, wool, meat, cotton, general food items and even coal also matter, in their products trade.

Business Presence

Since independence Kazakhstan has seen a gradual growth in the business activities of U.S. companies in also other areas of business than just pure trade on its territory. However, even these varied business investments are only a part of a much larger U.S. investment portfolio (on which, see the following section on Investments) in Kazakhstan encompassing not only, principally, the energy sector but also involve sectors such as mining, real estate, business services, chemicals, transport and communication, electric, gas and water production and distribution and also infrastructure, at a much lower level (Embassy of Kazakhstan in the USA (EKUSA) 2012).

In its more traditional sector, as hinted in the previous section, it is a major exporter of wheat. Kazakhstan envisions itself as a future agro-export power. It has boosted its productivity by adopting U.S. methods and machinery for harvesting and herding. In 2010, it airlifted more than 2,000 Angus and Hereford cattle from North Dakota as breeding stock. It plans to create feeding complexes for livestock under U.S. joint ventures to feed 5,000 heads of cattle (EKUSA 2013). Beyond the period of research, the figure has reached over 50,000 cattles per year. It wishes to adopt latest U.S. scientific methods for sheep and poultry breeding as well. Speaking of joint ventures, there were 374 U.S. joint ventures in Kazakhstan by 2009. Beyond the research period, this number has long moved past 400. Other than the many joint ventures in the energy sector like TengizChevroil, for more of which see the later section on energy dealings, the U.S. firm General Electric has a joint venture factory right in Astana (variously known in the past as Akmola and Tselinograd) itself, assembling railway locomotive kits manufactured and exported from Pennsylvania.

Anyway, in the newer business sectors generally, U.S. companies with large investments in Kazakhstan include Chevron, Kerr-McGee/Oryx, B.P., PFC Energy, IBM, AGCO Corporation, Boeings, Baker Hughes, Sikorsky Aircraft, Apache Corp., FedEx, Asia-Africa Projects Group, J.P. Morgan and Citibank (EKUSA 2012). For additional U.S. businesses and a brief sectoral representation of the same in the Kazakhstan economy, see Table 2.

Table 2: A selection of U.S. Corporations found to be active in various Kazakhstan Business Sectors

Business Sector |

U.S. Corporation |

Business Sector |

U.S. Corporation |

Agro Services |

AGCO Corporation |

ICT |

Aurora |

CaseNewHolland, Inc. |

Cisco |

||

Deere & Comp. |

IBM |

||

Philip Morris |

Microsoft |

||

RJR Nabisco |

Law Firms |

Baker Botts, l.l.p. |

|

Banks |

Citibank |

Bracewell Giuliani |

|

Goldman, Sachs & Co. |

Coudert Bros. |

||

J.P. Morgan |

Dentons |

||

Simmons & Co. |

Haynes and Boone |

||

Business Services |

Deloitte |

Morgan Lewis |

|

Pricewaterhouse Coopers |

White and Case |

||

Xerox |

Logistics |

FedEx |

|

Construction |

Bechtel Corp. |

Globalink |

|

Fluor Corp. |

M&M Air Cargo |

||

McKinsey |

Travic |

||

Parsons Corp. |

UPS |

||

Consultative |

Asia-Africa Projects Group |

Oil & Gas |

B.P.* |

APCO |

ChevronTexaco |

||

Halliburton International |

ConocoPhillips |

||

J.E. Austin Associates |

ExxonMobil |

||

McLarty |

Shell* |

||

Health |

Abbott |

Oil Services |

Baker Hughes |

AbbVie |

Kellogg Brown & Root (KBR) |

||

Baxter |

Noble Corp. |

||

Lilly |

Parker Drilling Co. |

||

Merck |

Schlumberger |

||

Hotels |

Hilton |

Transportation |

Bell Helicopter Inc. |

Inter Continental |

Boeing Company, The |

||

Marriot |

General Electric |

||

Radisson |

General Motors |

||

Ritz-Carlton |

Sikorsky Aircraft Corp. |

Note: Corporations are listed alphabetically within each sector; some of the corporations are actually multi-sectoral but listed here only in the sector deemed most appropriate; Banks, generally also dabble in consultative business. Those in Information Communication Technologies (ICT) may also delve into defense electronics. Similarly, most firms listed in the transportation and construction sectors are also involved in defense-related dealings, that are not directly dealt with in this article.* - Though these are basically Anglo-firms, they do have significant American interest and, therefore, are included.

Sources: Embassy of Kazakhstan in U.S.A. (EKUSA 2012); U.S. – Kazakhstan Business Association (USKBA 2014); American Chamber of Commerce in Kazakhstan (AMCHAM 2016).

Kazakh sources state there were between 50-70 U.S. firms in Kazakhstan by mid-1994. In 2000 there were about 150 U.S. firms in Almaty. To deeply ingrain the business culture, in 2002 both state parties launched a Business Development Partnership, known also as the Houston Initiative. Further still, as if to give a fillip to these trends, the World Bank named Kazakhstan as the world’s most reformed business economy in 2011. This, in turn, has served to attract even more U.S. firms to the Kazakh steppe, ever since. The hundreds of U.S. firms, now present in the various sectors, hold a leading position in the Kazakhstan market, excepting in sectors that remain as the sole preserve of Samruk-Kazyna and Baiterek.

Investments (FDIs)

In keeping with the American private sectors tendency to invest in various new and growth economies, and to when Kazakhstan begun welcoming foreign investments, particularly as Russia receded away in this respect, U.S. investment sources then gradually begun paying more interest to Kazakhstan, as a destination for their investments, especially after the conclusion of the OPIC agreement and the bilateral investment treaty (DOS 1992). First on the Kazakhstan investment scene were, of course, the U.S. energy corporations, since they already had an eye on Kazakhstan’s hydrocarbon riches even from pre-independence times (CIA 1993). Thus, it is no surprise at all to find American companies getting a head start, heavily invested and actively involved, particularly in Kazakhstan’s petroleum sector. On Kazakhstan’s part, conscious of the positive impact of investments on economic growth and employment, Kazakhstan has often encouraged foreign direct investments (FDIs). Boosting Kazakhstan’s reform efforts further, in this regard, were the endorsements of the “IMF, the World Bank, the EC and then-US secretary of state James Baker,” who even backed it with a supply of American economists (Rashid 1993, p. 49). Kazakhstan has seen over $122 billion in FDI inflow since its independence, with the last five years alone bringing in about $70 billion. Beyond the period of this research, total FDI in Kazakhstan was around $148.1billion in 2016 (The World Factbook 2016). A significant part, usually, over a quarter or at times, about just under one half, of these FDIs are directly from the United States.

Although Kazakhstan is not the largest recipient of the United States’ foreign direct investments, the U.S. is a dominant FDI source for Kazakhstan. In 2006 American FDI in Kazakhstan was 27% of the total (Weitz 2008, p. 125). United States’ FDI was 24.6 % of Kazakhstan’s total FDI in the first half of 2007, says one of the last Background Note: Kazakhstan to be available online at the U.S. State Department’s website (DOS-BN 2009). The U.S. percentages have increased further since then. By 2009 American companies have invested some U.S. $ 14.3 billion in Kazakhstan since 1993. This was despite the then obtaining less than favorable legal conditions and the, generally, poor investment climate, including the arbitrary enforcement of laws. Wanting to create a better investment and trade climate, the U.S. and Kazakhstan have had a Bilateral Investment Treaty and an Avoidance of Dual Taxation Treaty in place since 1994 and 1996 respectively, to cater to the needs of their investors and business peoples (DOS-BN 2009). To boost U.S. investments further, the first-ever Kazakhstan-U.S. Investment Forum was held in New York City in 2009, trumpeting afresh its desire to diversify, including through privatization, as per the Kazakh development plan and, generally, promoting its investor friendly climate (‘Kazakhstan-U.S. Investment Forum 2009’). The legal investment framework had subsequently been improved further, as a result perhaps, but also by a new 2011 legislation passed by the Kazakh parliament.

Presumably, the cumulative effects of these and other legal and business reforms saw the volume of gross inflow of American direct investments to Kazakhstan growing to more than U.S. $ 24.2 billion by mid 2012, i.e. within two decades of independence (EKUSA 2013). Still, the National Bank of Kazakhstan (NBK) puts it at 17.9 billion and states that the “Netherlands” hold top spot at $49 billion in early 2013 (Nichol 2013b, p. 14). Generally however, FDIs have shot up dramatically since the post-2001 period. As recently as 2011 alone Kazakhstan had raked in U.S. $ 1.039 billion in American FDIs. Flowing beyond the research period, American FDI in Kazakhstan has reached and is passing the $26billion mark in the period 2005-2017 and has even surpassed the Netherlands of late (Kazakhembus). Given that oil and gas is Kazakhstan’s leading economic sector, the U.S. has, appropriately, made its heaviest investments in that sector. But as mentioned or tabulated (Table 2) elsewhere, the U.S. has also invested in other Kazakhstani sectors like in trade, business services, real estate, telecommunications, transport, mining, repair services, electrical energy, gas and water production and distribution sectors and in the banking sector too, mainly via Citibank.

American B.D.A. in the Economic Sphere - The U.S. focus in this sector is on economic, fiscal, financial and trade policy, including economic liberalization, fiscal reform, improving economic transparency including by introducing auditing standards, energy sector reform including improving its regulatory environment and investments in energy efficiency, shaping a national consensus for the mining sector, addressing and reducing climate-change related emissions, privatization of state enterprises in a number of business sectors. Building national consensus in the banking sector and, specifically, building Kazakhstan National Bank’s institutional capacity (DOS-FOAA 2009). Sustainable development of natural resources, including oil, gas, water and others too, remains a focus.

Besides working to improve its public sector governance and capacity, Kazakhstan also joined the United States’ Economic Development Program which includes advancing the diversification of the economy, creation of small business support, promotion of economic competitiveness, regional integration, regulatory simplification and sustainable growth across economic sectors. Perhaps for this reason the Kazkommertsbank (Qazkom) has been allowed to specialize in the diversifying non-oil sectors. In these contexts too, “Kazakhstan became the first country” in 2006 “to share directly in the cost of a U.S. Government’s foreign assistance program” (DOS-BN 2009; EKUSA 2013). This program was subsequently extended to 2012, considering the mutual benefits it offers to both the U.S. and Kazakhstan. Specifically, in the context of the diversification of the Kazakhstan economy, after more than two decade of exclusion, the 4th Kazakhstan-American Investment Forum in New York on 7th December 2011 addressed newly, the development of strategic industries, with a higher manufacturing role, in Kazakhstan (EKUSA 2013).

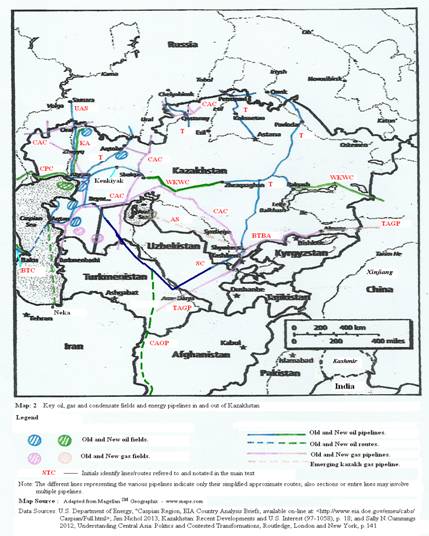

Indirectly, Kazakhstan’s increasingly market-based economy and its capacity to trade globally has been increased by American investments in the development of key institutions and infra-structure that facilitate and enable regional integration and opened-up alternative outlets for Central Asian resources, in general, to reach the world market (see Maps 1 and, particularly 2, later). In these contexts and with an eye to push diversification of the Kazakhstan economy further, the U.S. had contributed over $100 billion, in value, to various Kazakh entities by 2011.The U.S. commercial service runs business internships, it also offers various business services and exchanges across all economic sectors, including in the energy sector. In addition, it runs also matchmaker programs that link Kazakh firms with relevant U.S. businesses.

The U.S. has been running USAID assistance and activities in support of privatization, private entrepreneurs and helps in adopting commercial and regulatory laws; given Kazakhstan’s gradual embrace of market reforms, the U.S. supports the transition to market economy in Kazakhstan and, thereby, works to integrate it into the world trade system fully (USAID 1997). In this regard, the U.S. had for long supported Kazakhstan’s ultimate accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), expected at end 2015. Very broadly then, aid in the economic sector also includes that, specifically, geared to maintaining an open trade and investment environment. In other social and environmental sectors, the U.S. via the Global Health Initiative (GHI), supports and helps the Kazakh government to provide effective social services, including by combating HIV/AIDS, addressing multiple-drug-resistant TB and offering help in basic health care and environmental protection. The U.S. and E.U. worked with Kazakhstan to establish in 2001 a Regional Environmental Center (REC) at Almaty (DOS-BN 2009). American aid to Kazakhstan is not all confined to politico-legal, socio-economic and enviro-developmental sectors alone, however. Another important policy area of developmental assistance is the defense and security sector. For more on this matter, see at the end of the sub-section on Defense and Security Ties within the next domain, i.e. Strategic Realm.

Strategic Realm

In keeping with its long sustained objective of preserving its global pre-eminence, even in a post-Cold War world of presumed lower strategic competition, the U.S. characteristically went for the key states/players of the emerging ex-Soviet Central Asian region. Along with countries like Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, the similarly interesting entities of Afghanistan and Xinjiang too figured brightly in its strategic calculations if not also on its politico-economic radar. This, however, does not mean that the lesser endowed countries of the region, escaped its entrepreneurial, if not also strategic, attention, especially so when they manifestly possess other energy and mineral assets, to get the U.S. interested.

Whether, the U.S. realizes this or not, states like Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan in Caucasus/Central Asia region do admire America’s post-Shah, exemplary role in the Persian Gulf area. They are attracted to the business successes and developmental models of the U.S. energy companies and other MNCs in that region and wish the same could be adapted and emulated in their region too. On average, Central Asian states view America’s good relations with Turkey, a key Muslim-Turkic state, as a model to aspire to, though America’s idealistic push for an overnight democratic-credential down their throat is a bit difficult to ingest in the short term (Weitz 2008, pp. 129-130). Though America’s attitudes in the Russo-Georgian and Ukrainian crises, before and after it, were and are not intended primarily as tools to impress the non-Russian NIS generally, the Central Asians, nevertheless, could not help but take astonished, if not also cautious, note of those too.

Still, in this context, Kazakhstan, a state with enduring fraternal Eurasian ties to Russia, kept its equi-distance intact between the U.S. and Russia. Kazakhstan works hard to equitably regulate its ties with both these key powers and constantly aspires to balance them. This Kazakhstan foreign policy ambivalence was noted in America much earlier even by the Library of Congress’ Country Study: Kazakhstan (FRD 1997). With Russia’s initial disinterest vividly in mind, it is, understandably, cautious too about Russia’s continued reliability and viewing contrastingly, especially America’s military-first approach in the greater Middle Eastern region with concern, it at times goes easy on U.S. overt impetus for deeper intercourse. As far as the Kazakhs are concern, they welcome and are happy if the U.S. confines its role to just “stock and hoe” and hazard not into “shock and awe” as they are habitually prone to, west and south of the Kazakhstan backyard. In these contexts, Kazakhstan also maintains its multi-vectored balance not only by being a member of the CSTO, ECO, OIC and SCO but also by having security dialogues with Asean and even initiating on its own, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-building measures in Asia (CICA) to multi-laterally and institutionally underpin the same. Beyond this research period, it had been bidding for a non-permanent seat in the UN Security Council since 2014 and won the same for 2017-18 on 28 June 2016, presumably, with P5, including American, support for pursuing its peace-driven objectives.

However, mindful of the difficulties of its strategic neighborhood and the potential instabilities arising from the recent drawdowns and the then looming post-2014 American “exit” from Afghanistan, Kazakhstan was and is particularly anxious to keep all its neighboring powers and the United States equitably and positively engaged with it and to be relevant and available in its developmental immediate futures, particularly, towards the pursuit, in the short-term, of its visions 2030 (Nazarbayev 1998) and 2050, over the longer haul. As if to keep in step with these legitimate Kazakh anxieties, according to the DOS, the strategic aim of the United States “in Kazakhstan is to ensure and maintain the development of the country as a stable, secure, democratic, and prosperous partner that respects international standards and agreements, embraces free-market competition and the rule of law, and is a respected regional leader” (DOS-FOA 2013; Nichol 2013b, p.21). Anyway, the two key sectors through which those concerns and lofty objectives may fruitfully be realized in the future are now analyzed here. As you may care to notice, though energy issues are normally dealt with in the economic sector in most analyses, I have, however, chosen to deal with energy dealings within the strategic realm, in this article, because being the dominant economic sector and the real driver of the overall Kazakh economy, its impressive growth and given its strategic dimension, as it is constituted within the U.S.-Kazakhstan relationship, this, I feel justifiably, should be its appropriate slot.

Energy Dealings

Having been kept out of Kazakhstan’s territory during Soviet times, American energy corporations seized the opening to the region’s resources offered by Kazakhstan’s imminent independence. The U.S. administration of the day, long plagued by the need to diversify its energy supply sources and well represented by the oil lobby, need not be invited to bandwagon. Thus, the Soviet monopolistic hold over Kazakh petroleum resources, in particular, came to a rapid end.

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates Kazakhstan’s oil reserves as 9-40 billion barrels of proven reserves and an additional 92 billion barrels of possible reserves, thus giving Kazakhstan an oil reserves total of anything between 101 to 132 billion barrels. Kazakhstan’s oil reserves have continued to grow gradually as relatively positive exploration results seep in, if only in fits. The CIA has quite regularly stuck to the 30 billion barrels of reserves figure (The World Factbook 2016). Over a hundred hydrocarbon fields have been discovered and more than 200 hydrocarbon concentrations have been identified. Its main offshore hydrocarbon fields are Kashagan and Kurmangazy and its onshore fields include Aktobe, Mangistau, Uzen, Tengiz and Karachaganak (Olcott 2007, pp. 62-66).

In 2001, Kazakhstan and the U.S. established an Energy Partnership. Perhaps as a consequence Kazakhstan is fast emerging as a key petroleum producer in the Central Asian region and it has become one of the world’s major crude oil producers, especially after 1998. Kazakhstan’s output stood at about 900,000 barrels per day in 2004. This fact alone is largely responsible for increasing Astana’s state revenue. Kazakhstan’s oil production is rapidly increasing. It nears to doubling every five years since 1995. However, it has not kept to this trend since 2005 when the output was 1,288,000 barrels per day and it rose to only 1,525,000 barrels per day in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau). In 2008 the production figure was 1,345,000 barrels per day. It was believed to be hovering at under 2,000,000 barrels per day in 2013 and was, beyond the research period, slated to reach 3,000,000 barrels in 2015. Kazakhstan exported an estimated 1.466 million barrels per day in 2013 (The World Factbook 2016). As a non-OPEC nation Kazakhstan is not bound by any fixed production quotas, however, in the interest of maintaining a healthy price level, it maintains voluntary constrains under various guises.

There has been a high convergence of the private sectors of both the U.S. and Kazakhstan in energy partnerships. Through these energy co-operations U.S. majors hold leading positions in the Kazakh energy market. Unlike many countries in the Middle East, Kazakhstan exploits its oil resources via joint-ventures or PSA operations with international oil majors. Thus, it is no surprise to find many energy multi-national corporations, including American ones operating various energy projects in this key sector of the Kazakh economy. While Kazakhstan’s oil may not be relatively cheap to produce, it is of sufficiently high quality to attract most oil majors to invest. In fact, the oil industry has been willing to spend 10s of billions of dollars annually in this sector.

Depending on Western, including American, oil corporations’ good behavior, in terms of allowing adequate Kazakh equity stakes, in their energy consortia, tax settlement, Kazakhization, environmental responsibility and good social infrastructural help, the Kazakh government rewards them with additional contracts if not also concessions, such as cancelling fines and duties. The nature of Kazakhstan’s dealings with Chevron and later with ExxonMobil (Schreiber and Tredinnick 2008, p.67) too, comes to mind in this regard. Very broadly, U.S. corporations are involved in both hydrocarbon field development projects and energy transit pipeline projects in Kazakhstan (please verify the general locations of these in Map 2).

Hydrocarbon field development projects - Some of the specific Kazakhstan-linked large energy projects, where American corporations’ equities are inevitably involved, include hydrocarbon field development projects such as:

Tengiz – At 20% of production its operator TengizChevroil has been the largest producer of hydrocarbons so far in Kazakhstan. Between 1993 and 2009 about 177.9 million tons have been extracted from the Tengiz field and paying the Kazakh government some $43 billion in taxes and royalties (EKUSA 2013). Beyond the research period, these have more than doubled by 2015 (PKAJ 2016). American equity holders in the TengizChevroil consortium are: Chevron 50 %, ExxonMobil 25% with 20% held by the Kazakh government via KazMunaigaz and the remaining 5% by LUKArco (DOS-BN 2009).

Karachaganak – The Karachaganak Consortium known also as the KIO is involved in exploiting this gas condensate field. About 70 % of the KPOC’s oil exports exits via the CPC. The Kazakh government subsequently demanded a 10% stake in the consortium whose American equity holder was Texaco originally at 20%. Shell, Chevron and Lukoil have major stakes in KIO. Even with oil prices sluggish, 141.7 million barrels equivalent of condensate was produced from this field in 2015.